John Cage

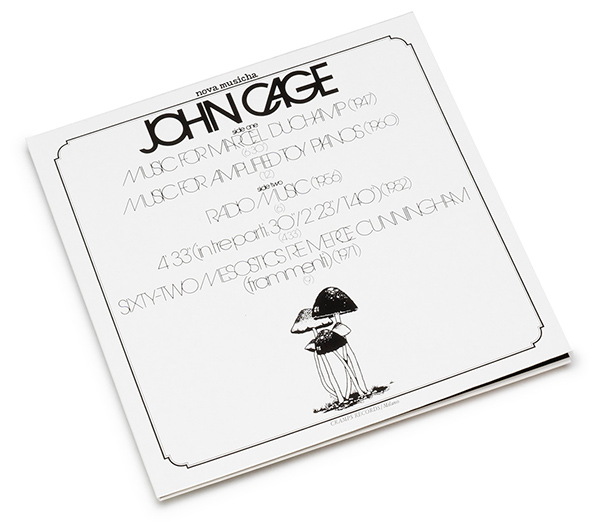

Of all the historic labels associated with experimental music, few have been as important as the Italian imprint Cramps. Relatively short lived, running for only seven years, its catalog reads like a who’s who of the 1970s musical avant-garde, housing seminal albums by Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, Giusto Pio, Demetrio Stratos, Juan Hidalgo, Robert Ashley, Walter Marchetti, Cornelius Cardew, Raul Lovisoni / Francesco Messina, Derek Bailey, and numerous other luminary figures. With the vast majority of these albums having remained largely out of print and nearly impossible to obtain for decades, recently the Milan based imprint, Dialogo, has begun their own series of vinyl reissues from the Cramps’ catalog, but have only begun to scratch the surface of this remarkable body of work. Running adjacent to this, Sony has also waded in over the last few years with their own initiative, delivering reissues by Area, Demetrio Stratos, Claudio Rocchi, and a handful of others. Now they've taken this one step further with a stunning, brand new vinyl pressing of one of the most sought after releases in the Cramps catalog, John Cage’s self-titled album from 1974, that launched the label’s “nova musicha” series. Out of print for decades, now pressed on 180 gram white vinyl in a very limited edition of 500 copies, it’s a crucial artefact within the output of one of the 20th Century’s seminal composers, and a rare chance to dive into where one of the most important bodies of experimental recordings all began.

John Cage needs little introduction. His name is synonymous with experimental music, a term he popularised for music for which, at inception, the outcome is unknown, starting in the early '60s. Born in 1912, and a bridge between earlier generations of avant-garde composers like Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg, both of whom he studied under, and numerous successive generations that followed their and then his wake, Cage pioneered and popularized numerous radical approaches to the organization of sound / composing, including indeterminate music, electroacoustic, non-standard use of musical instruments - “prepared”, etc. - and non-instrumental sound sources, among others. First appearing within the musical landscape during the 1930s, Cage is also important for his forging of ties between the worlds of visual art and sound, first through relationships with artists like Max Ernst, Piet Mondrian, André Breton, Jackson Pollock, and Marcel Duchamp, and then through his association with Fluxus, as well as artists like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Cy Twombly, not to mention his close ties to other disciplines like dance, via his partnership with the choreographer Merce Cunningham.

Cage, not unlike Derek Bailey, was deeply critical of the recording and mechanical distribution of music, preferring it to remain in a fleeting, temporal present that required more of the listener and artist alike. This makes the substantial body of recordings he left behind, not to mention the thousands made of his music by others, slightly complex. Much of Cage’s earlier works could be seen as radical cultural interventions; wedges placed between the old and the new, but as the '70s began his legacy was more or less secure as one of the most important composer’s of the century, which allowed for a softer, more playful temperament to emerge; a lover of mushrooms and naturally occurring sounds.

While it contains works dated from across the period between 1947 and 1971, Cage’s Cramps self-titled release, issued in 1974 as the first entry in their “nova musicha” series is a lovely window into this emerging image of Cage’s personality. With two of its works dedicated to other artists in his life, Marcel Duchamp and Merce Cunningham, and were played by noteworthy figures on the experimental music scene - Juan Hidalgo, Walter Marchetti, Gianni-Emilio Simonetti and Demetrio Stratos - it also helps illuminate Cage’s important connections to artistic practice both within and beyond sound.

“John Cage” comprises five pieces over its two sides - “Music for Marcel Duchamp” (1947) “Music for Amplified Toy Pianos” (1960) “Radio Music” (1956) “4’33” (In Three Parts: 0'30"/ 2'23"/ 1'40"”)” (1952) and “Excerpt from 'Sixty-Two Mesostics Re Merce Cunningham” (1971) - effectively operating as a survey of some of the composer’s most distinct and important works, as well as how he have seen (or wanted to present) himself during this period of his career. Most of these also, importantly, represent some of Cage’s most engaging and listenable works.

The collection's first composition, “Music for Marcel Duchamp”, is an early work for prepared piano, in the realisation performed by the legendary Spanish composer Juan Hidalgo. Light, playful, and melodic, while threaded with surprising dissonances and muted sounds, it represents a fascinating window into Cage’s radical break with tradition, stepping clearing over Serialism and establishing a tangible link between the music of Erik Satie and sounds that would come to define the post-war avant-garde during the decades ahead, partially within the work of Morton Feldman and minimalists. From here we race 13 years forward to 1960 with “Music for Amplified Toy Pianos”, played by Hidalgo, Gianni-Emilio Simonetti, and Walter Marchetti. Across the 12 minute work we catch a vision of how far Cage had come over that time without loosing his connection to where he began. Even more minimal and sparse - long moments of silence and resonant tones falling between the punctuation of notes - this rendering of this heavily recorded work is possibly the best ever laid to tape, each player responding to the next with particularly aggressive attacks.

The second side begins with a marked absence from the piano, with “Radio Music”, one of the works that brought Cage an elevated level of fame during the 1950s. Here the composer - placed in the hands of Simonetti, Hidalgo, and Marchetti for this rendering - weaves the sounds of scrolling radio - static, fragments of broadcasts, etc. - into a total, immersive composition that represents one of the most distinct uses of non-instrumental sound sources during the post war period, writhing, churning, and rewriting the very conception of music every step of the way. This is followed by “4'33"”, arguably his most famous composition, during which a player sits at the piano silently. Here Cage draws focus to musicality of the ambient sounds of the room and those made by the listener(s), which is no less active when engaging via a hi-fi system than it would be in a concert hall. The side and collection concludes with an absolutely stunning realization of “Sixty-Two Mesostics Re Merce Cunningham” a work delivered to startling heights by the vocal wizardry of Demetrio Stratos, howling, humming, crying, squeaking to almost inhuman effect.

It’s hard to think of any better renderings of Cage’s works than those that appeared via Cramps in 1974. In the hands of some of the most important and distinct composers to follow in this wake during the later half of the 20th Century - Stratos, Simonetti, Hidalgo, and Marchetti - every moment and sound comes alive and jumps from the speakers. Whether a starting point for those just beginning to explore Cage’s work, or the devoted fan, this is unquestionably one of the most important bodies of recording in his catalog. It’s insane to think it’s been out of print for so long. Sony has done a beautiful job with this white vinyl edition of 500 copies. Just about as essential as they come.