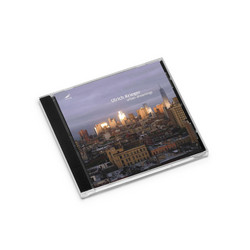

Today it is well known that Austrian pianist and composer Friedrich Gulda was at home in two different worlds: classical music and jazz. He once mentioned “There are so many great musicians alive, but none of them was able to tear down the border that was created by the music industry, which is the border between classical music and popular music. Jazz is still considered to be something deserving less respect.” Gulda was one of the few who tried to cross that border, working in both realms, without regard to how he was perceived by critics and other musicians. The young pianist attempted to conceal his love of jazz. Raised in Vienna, the piano prodigy was only 20 when he played his Carnegie Hall debut. After the concert he went to a jam session at Birdland, New York's legendary jazz club. For him, jazz offered “the rhythmic drive, the risk, the absolute contrast to the pale, academic approach I had been taught.” Still, he had to admit “There sure is no guarantee for me to become a great jazz musician, but at least I am serving the right music.”

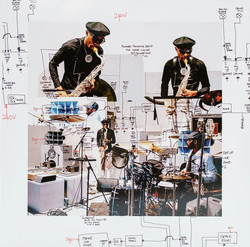

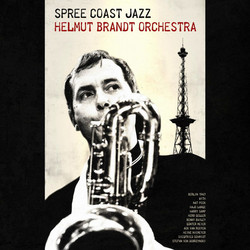

In 1951 he joined the group of Dizzy Gillespie, who wanted him to stay for at least a year, but Gulda left to return to Vienna. A few years later, in 1956, Gulda played Birdland for two weeks, and in July the same year at the Newport Jazz Festival. When in 1962 the 11th “Berliner Festwochen” took place, Friedrich Gulda was invited to play both classical and jazz music. He opened with Beethoven’s piano concerto no. 4 in G major. For the jazz concert, he put together an ensemble of the best musicians from Holland, Austria, England, Sweden, Norway and the USA. The recordings of that early October night in 1962 at the Auditorium Maximum of the Berlin University are released here for the very first time. Bass player Georg Riedel from Stockholm, who is featured here on his composition “Die Neue Bassgeige”, remembers “We rehearsed for a couple of days and since I was in Berlin, I also went to East Berlin to see what it looks like. I bought some books and also records from Russian composers like Shostakovich. On my way back at the border I was asked a lot of questions and almost came too late to play the concert.”

Gulda also sometimes played the baritone saxophone and solos here on “Music For Three Soloists and Band“. Georg Riedel looks back “He sometimes played that horn, but since I am from Sweden, I was just used to more brilliant baritone players like Lars Gullin. However, we thought that Gulda was much better at the piano anyway than at the baritone. Jazz was something exciting for Gulda and we thought, that he played classical piano so well. Sometimes when we took a break at the rehearsal, Gulda sat down at the piano and played a movement from Beethoven, which was just fantastic, we were all very touched.” Three of the featured compositions are classics from the bebop era. The up tempo piece “Anthropology” and two ballads, “Round Midnight” and “Lover Man” that is played by trumpet and saxophone only and matches the slow piece perfectly. The audience was quite excited as you can hear on the recording.

It was exactly this group of Gulda that went into a studio in Saarbrücken and recorded the LP “Music For Piano And Band“ on September 28-30 in 1962, but it lacks the live feeling that Gulda’s group had at the following concert at the Berlin Auditorium. Gulda’s fascination with jazz derived from his desire to improvise. “The little freedom every interpreter of classical music has is between zero and ten percent. So they are very limited. Whereas improvised jazz is in the middle, somewhere between ten and eighty percent. The aspect of improvisation for me is standing above all. That doesn’t exist in jazz music only. It exists in every good music, but jazz music today is the most important manifestation of improvisation.” .