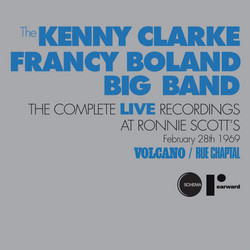

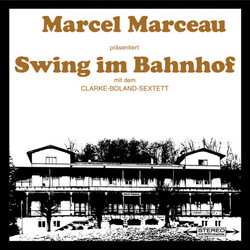

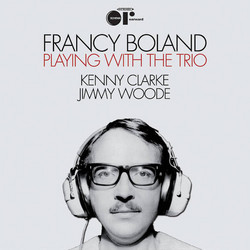

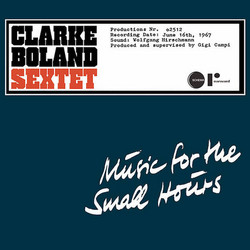

Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band

Rue Chaptal (LP)

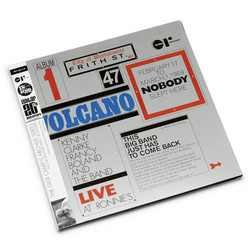

It is a few minutes after ten-thirty on Monday evening, February 17, 1969, in Ronnie Scott’s, 47 Frith Street London W I.

On this particular Monday at Ronnie’s something special is about to happen. A new attraction is to begin a two-week engagement at the club, and this attraction is out of the ordinary. The word has got around, from people who have seen one of the concerts which preceded this opening and others who know the band from records or foreign festivals, that this is a team not to be missed—especially in such a jazz sanctum as Scott’s.

The area in front of the liggers’ bar is thickly populated with musicians, journalists, ‘resting’ critics and broadcasters, radio, TV and record shop personnel and other familiar but unidentifiable members of the species known as ‘regulars’. The club’s owner walks purposefully up to the microphone, makes a few sardonic remarks about his customers, and announces, with suitable compliments, the Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band which will play its first set.

He then, for Scott is no run-of-the-ginmill proprietor, takes his place in the reed section behind a tenor saxophone.

He is flanked by Sahib Shihab, on his left, and on his right by Derek Humble, Johnny Griffin and Tony Coe. This Anglo-American quintet is one of the orchestra’s crowning glories; largely so because Boland writes choruses for it which enable the five musicians to function and flower as an enthusiastically coherent melody section, led, and most effectively, by British alto player Derek Humble.

One, two, boom, boom … while I’m trying to lip-read what Griffin is saying with such emphasis, somebody has counted the band in. It’s off on a fast blues and at once all is rhythmic propulsion, crunching brass and vivid orchestral colouring. This outfit doesn’t need long to fire up. The brass, thickly and brightly scored, hits clean and hard. The saxophones produce power and tone, slugging it out (if they will pardon the expression) with a potency that brings back memories of Jimmie Lunceford as well as Duke’s regal reeds.

And the rhythm quartet settles quickly on a pushing, driving beat which the organization fully wound.

First soloist to emerge, through a fusillade from four drum hands, is Idrees Sulieman. Applause at the end and Boland takes over, with ideas a-plenty. After him there is space for Derek Humble, Dusko Gojkovic, the fluent Åke Persson and baritone champ Sahib Shihab. The punch of the ensemble, booted by the drum team. is formidable. As the last chord screams across the room the patrons respond with untypical rapture.

This is something like it, the verdict seems to be, something like it was when the cash customers used to be taken into account. Clearly this is a band concerned with communicating in terms the listeners understand and with establishing a happy, participative mood. The ensemble boasts discipline and fair precision but also the kind of flair which can translate a composer’s intentions into ardent performance. Francy Boland, slick in a big red bow tie, has moved front to conduct the band out. He looks pleased with the reaction in a modest way, tells us that the number was “Box 703”. This, if memory serves me, is named after the postal number for Willis Conover’s Voice Of America radio programme. It has been used as an opener since the band’s first album, “Jazz Is Universal”, which means it goes back to 1961 and the days when the instrumentation consisted of six brass, four saxophones and three rhythm.

I recall that Benny Bailey, Åke Persson, Nat Peck, Derek Humble, Sahib Shihab and Jimmy Woode were in that early band, too, as well as the co-leaders. Which is a lot of continuity for an ad hoc organization to achieve, and a part-explanation of the mutual understanding so clearly shown by the players.

As it happens, Woode is not present at Ronnie’s and his place has been filled by Ron Mathewson. This young Scottish bassist seems to be filling his somewhat daunting role admirably, and as the programme unfolds he sounds better and better. Tony Fisher, in the trumpet section, is another newcomer. But he has already played a few concerts with the band.

Now, the Belgian co-leader—who avoids the spotlight as much as he can—is saying that they are going to play “Griff’s Groove”. The effect, through the loud-speaker system, is strange and indistinct over the hubbub. A neighbour leans towards me to shout: “What’s that? Il sounds like a train announcement at Charing Cross station”.

Who cares, though? Boland has waved the fifteen men in and returned to the keyboard. The groove is Basie-like, the saxophones loping at an easy blues pace. Trombones exclaim, the trumpets make a point and the band builds section on section to the entry of the “Little Giant”. Griffin, soloing greatly, is followed by Bailey, tough-chopped trumpet lead and one of the orchestra’s principal soloists. Then Griff returns to carve out a “deep” blues improvisation against the tutti.

The first statement is recapitulated after the tenorman steps back.

This is one of a series of scores done by Boland for the Basie band, and it must have suited that ensemble down to the ground. It’s right in the Basie blues tradition but, like so many of Francy’s arrangements has a singing melodic property which lingers in the mind. The sounds recall Basie, but they are Boland’s own, and Griff’s and Bailey’s.

And so the set proceeds, the band revealing different textures and tone colours, different facets of its composite personality, through the medium of Boland’s skilled and intelligent writing and the various featured instrumentalists on “Volcano”, “Now Hear My Meanin” and other CBBB originals. At Ronnie’s, by the end of this electrifying first night, the audience vociferates its approval. Bandsmen smile a trifle wearily, Kenny Clarke grins what Mike Hennessy termed his thousand-candle-power grin, and even the diffident Boland admits he is happy with the reception.

This is only the beginning. Each night the word spreads farther; more people come to hear the occasional ensemble with the togetherness of a permanent band, and many who have experienced its maximum impact return, in some cases again and again, for another pleasurable shock treatment. Around the bar, discussion is animated and most of it flatters the band’s efforts. Seldom have I seen so much extrovert enjoyment at the Scott Club. The critics too, greet the CBBB as they might a fresh breeze on a sultry night. “Stuff your eiectronics”, instructs a “Melody Maker” reviewer. “There is nothing to compare with a top-class big band in full flight. And the place to hear it is in a club rather than the cold confines of a concert hall … Make no mistake, this is one of the great bands—I find it both more exciting and more satisfying than either the Woody Herman or Buddy Rich bands, both of which have roared away in the same setting.” The first week is a remarkable success, and the second is even bigger. Attendance records for the club are broken. Musicians and celebrities of one kind and another visit Ronnie’s among them Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon; Amen Corner, Rex Harrison, Peter Sellers, Samantha Egger, Chris Barber, the Rolling Stones etc.

The culmination of the band’s short London season is a series of “live” recordings at the club.

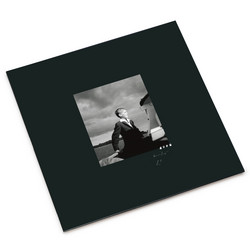

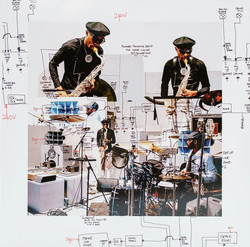

CBBB has been caught on record, just as it wailed and grooved and pleasured the senses in the relaxing atmosphere of Ronnie Scott’s, and you can savour its well-organised and co-ordinated performances on this and a companion LP. I hope that the musicians’ joy in music-making, their control of tone and attack, their natural (rather than artificial) sense of dynamics come through the record player as they carne across the smoke-laden air at Ronnie’s. I believe that they do. As you listen to the First Set, recorded from 10.30 onwards on the Friday evening (February 28), you will be able to hear a little of the applause and crowd noise, a touch of announcing and then the up blues, “Box 703”, with its nice ‘spread’ on stereo equipment. You’ll hear a lot of drumming, too. Clare with brushes, is in evidence now on your left; Clarke is coming out of your right (stereo) speaker. Both are cracking it out, their styles compatible and their sounds, including bass drum tones, distinctively different.

The main soloists on this selection are indicated on this cover. Interestingly, you can hear Griffin not quite on mike for his entrance on “Griff’s Blues”, and fancy him walking in as he realizes it. You’ll hear Kenny Clarke’s cymbals on right, also the good sound of Mathewson’s bass in this setting, and at the climax of the blues you can really hear Bailey grandstanding.

On Clarke’s composition “Volcano’” (scored as all these are by Francy) almost the whole band gets to stand up for a series of two-bar breaks—old swing-band fashion. It’s all the horns, I guess, except the tones who are busy elsewhere. Then it is Clarke’s turn, and Clare’s, and they complement each other perfectly. Notice the tightly written coda. And it is Bailey on top again … who else?

An unusual unison at the beginning of “Love Which” is typical of the arranger’s thoughtfulness in writing for instrumental groupings. Boland uses his little bands within the band in ways which are seldom obvious. “He likes”, as Klook tells me, “to hide his subtleties.” He is, it seems to me, always trying to write in the language of pure jazz. It is rooted in tradition but, in a totally unforced way, it’s the language of the Sixties. This part of the “Inferno Suite” shows the textures he can create, and right up to the fine final chord.

“Now Hear” is Jimmy Woode’s piece, a romping soul exercise which has Humble, Persson and Shihab sounding good, and the drum duo filling-in and accenting splendidly. And thus to the finale, again from Boland’s “Inferno” and spotlighting the two Kennys—with Klook Clarke on the right-hand speaker as always, providing you have a stereo rig. I’m not by nature a drum-solo lover, but Clarke and Clare come as near as anyone can to converting me—to drum duets, anyhow. Behind most worthwile jazz orchestras (or in the centre of them, perhaps I should say) is one man whose conception of music-making—and this should embrace pleasing the listener, though sometimes it doen’t—gives the group its character. Now and again, the master-minding is done by two.

This is the case with CBBB: Francy providing the repertoire and Kenny the unpretentious swing—the spirit is there! Listening to the CBBB for the first few timer does not disclose what its style may be. It has no gimmicks, unless you believe the drum duality to be a stunt, which it isn’t, and owes allegiance to no particular idiom, period or category of jazz expression. Boland is an open-minded and mature musician, receptive to influences but sceptical in the face of fashions and dogmatic theories about modernism in music. Progress, he seems to imply, is all very well; but so is tradition. Jazz techniques have come a long way in half a century, and Boland is prepared to make use of what appears to him valid for this particular collection of musicians. He writes, like Duke Ellington, the man he most admires in jazz, for the men in the band and for their distinctive sounds. Once he arranged for a single drummer. Now he must chart the course of a two-percussion team, leaving room for individual expression within the framework.

It’s hard to believe, soaking up the spontaneous air of the drum tatoos, that they are charted. But I have Klook’s word for it.

‘‘Francy writes for us”, he says, “so that cuts the problems down. Everything is planned. Francy studies the individual. He knows how I fill in and he knows how Kenny Clare fills in, and when it comes off, well, that makes it a corporation extraordinaire”. - Max Jones