Nailed as John Fahey’s ‘non-Christian religious album’, where he ‘found’ Eastern religion and kick-started the New Age movement, Fahey said, in 1990, that it was his greatest guitar record. Considering the often-puzzling self-mythologizing that accompanied earlier albums, Fahey’s sleeve dedication to “my guru, Swami Satchidananda” and booklet extolling the virtues of Yogaville West, “a growing spiritual community in the beautiful mountains of Lake County, Northern California” were shockingly untypical. Fahey appeared to have found a different kind of religion, declaring the virtues of, “this healthy, spiritually based concept of living”.

It reeks of another Fahey wheeze. There had to be a catch, and there was. Fahey was in love with Swami’s secretary, Shanthi Norris. He had already dedicated a track to her on “After The Ball”, maintaining a tradition which would see him namecheck current wives, girlfriends or infatuations, but he had never previously gone so far as sobering up, moving into a yoga commune and dedicating an album to his guru, while playing benefits, as a hopeful passport into his Swami’s secretary’s affections. “I didn’t believe in Krishna or anything. It was like being in the middle of The Thief Of Baghdad,” he confessed to Byron Coley in 1994.

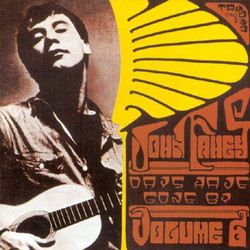

If the music had been weak, Fahey could have blown it. After his previous two albums for Reprise, which ventured into Dixieland jazz to scathing reviews and poor sales, he returned to Takoma, sat down with his 1930s Gibson ‘Recording King’ guitar at Hollywood’s United Recording Corp studios and played three lengthy solo pieces which required just one edit. They are so intricate he later said they were ‘too demanding’ to play live.

Fahey took the album and song titles from American poet T S Eliot’s “Four Quartets” suite. Fahey had spent time in India and experimented with raga forms years earlier on “Dance Of Death”. Like modern European classical and avant garde forms, it was just another musical strategy absorbed and set free in Fahey’s music at that particular time. Despite the Eliot/Swami store-front, Fahey was still heavily into recycling his old work. The 14-minute When The Fires And The Roses Are One snakes around its stately theme with an unearthly calming effect and runs into 1968’s Requiem For Russell Blaine Cooper near the end. Thus Krishna On The Battlefield is the album’s black cat moan, with Fahey’s string-damaging attack hitting an almost banjo resonance before stretching dark, bluesy and beyond.

The seeds of the spellbinding 23 minute title track were planted in 1965 during the ill-fated trip Fahey made to New York City at the behest of Elektra to record a blues instruction album and demo tape, both rejected and then lost for years. The original can be found on Ace’s reissue of “The Yellow Princess”. Fahey uses the motifs to head off on a stunning excursion through intricate melodic stretches where he speeds up, slows down and circles snatches of When The Catfish Is In Bloom, whose own blueprint debuted on 1968’s “Requia”. It’s a mesmerising reverie which comes to rest with a nod to Dalhart, Texas 1967 from “America”.

This album has long been a sought and highly-priced Fahey classic. Now out of time and Fahey’s chaotic career path, “Fare Forward Voyagers [Soldier’s Choice]” can stand as another monument to Fahey’s genius at work.