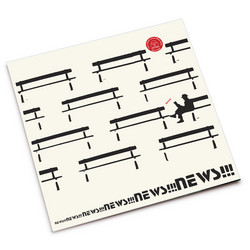

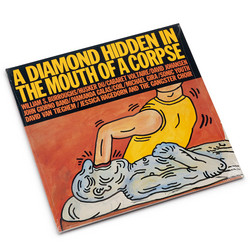

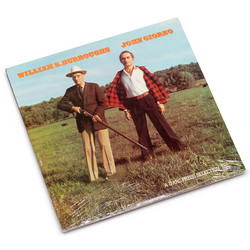

Genesis P-Orridge, Einsturzende Neubauten, Dave Ball, William Burroughs, FM Einheit

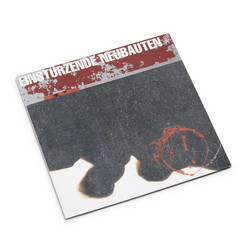

Decoder - The Soundtrack (LP)

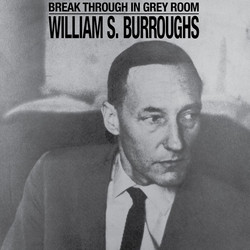

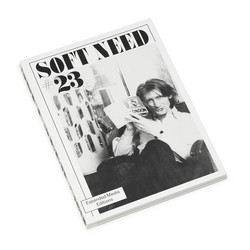

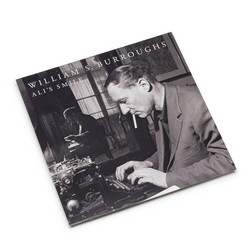

The film was made in Hamburg and Berlin, and directed by Muscha (who directed several punk films). The lead roles are played by Christiane F and FM Einheit from Einstürzende Neubauten, who also contributed to the film’s score. Genesis P-Orridge (from Psychic TV), the kingpin of the English industrial scene, also appears as a priest of the Black Noise faith. Author William S. Burroughs portrays an insurrectionist salesman of audio equipment, and American cult actor Bill Rice plays a detective. Matt Johnson from The The wrote a frenetic, deformed song for the film that is both fantastic and painful to listen to: “Three Orange Kisses from Kazan.” But Dave Ball and Genesis P-Orridge composed the rest of the soundtrack. (Dave Ball was the other half of Marc Almond’s Soft Cell, at the time one of the biggest groups in the English underground electro-pop scene.)

Decoder is split into three parts, each one filmed through a heavily saturated primary colour filter of red, green or blue. (The first decoding is of the power of colours.) It’s a futuristic film, a joyous application of William S. Burroughs’ The Electronic Revolution, which proposes a seditious and rather poetic method of subverting the masses and inciting them to rise up against the forces of order. The general idea is that insurrectionists should place loudspeakers in the streets to simulate riot sounds and conjure up imaginary disturbances, fostering a permanent sense of insecurity and terrorizing the enemy. It’s all intended to create an atmosphere that would cause actual riots. Appropriately, Burroughs himself was given the role of the audio equipment salesman who is secretly fomenting revolution from inside his dusty little shop.

The “hero” is played by FM Einheit, who one day realizes that the food served in the city’s fast food joints and the muzak being piped into them are two sides of the same coin – a massive program intended to control the masses. A priest from the secretive and sect-like Black Noise order then instructs him on the rudiments of manipulation. Together they attack capitalism by using anti-muzak and sonic terrorism. They cause riots and general hysteria by distributing their cassettes to the people. Once the ground has been made fertile for revolution, the masses are then subverted using “the black noise.”

The film may have denounced muzak – seen as a symbol of consumerism’s stranglehold on the world – but its soundtrack actively flirts with it. Dave Ball and Genesis P-Orridge shrewdly hijack elevator music for their own ends: alongside loops taken from actual muzak records are synths that pump out slow, almost funky grooves, a few jazzy spirals of piano notes intertwined with bleeps, samples, grinding sounds, reverb and whispers that could be either sensual or menacing. Decoder rejoices in its dialectic between “muzak” and “black noise” in various ways, looking to take as many liberties and make as many exaggerations as it can get away with.