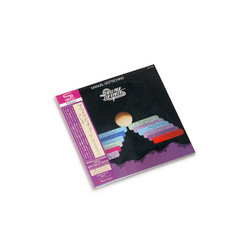

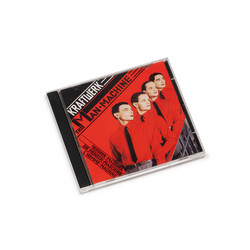

**2025 Stock. 180g Translucent Red Vinyl, German version ** Released in 1978, Die Mensch-Maschine (issued internationally as The Man-Machine) is Kraftwerk’s seventh studio album and the moment their cool, mechanised aesthetic snaps into its most iconic form. Built around the idea of humans and machines merging into a single functional organism, the record imagines the band as a kind of in-house design team for a coming cyborg society: four immaculately dressed figures fronting a music that is all clean lines, primary colours and perfectly calibrated motion. Concept, visuals and sound lock together with rare precision, turning the album into a kind of prototype for how electronic pop could look and feel.

Across six tracks, the group refine their rhythmic and harmonic language into something both more minimal and more overtly dance-oriented than before. “Die Roboter”/“The Robots” opens with a now-classic sequence of synthetic stabs and vocodered self-introduction, announcing a band who are simultaneously workers, products and mascots. “Spacelab” stretches out on slow, weightless chords and pulsing bass figures, a weightless orbit viewed from the console rather than the cosmos. “Metropolis” pays sonic homage to Fritz Lang’s film, its interlocking patterns suggesting a city run on perfectly timed circuitry rather than steam. On the second side, “Das Model” (“The Model”) distils obsession and surface into three and a half minutes of deadpan synth-pop that would, years later, become a surprise number one single in the UK, while “Neonlicht” (“Neon Lights”) unfolds as an eight-minute nocturne, a long, gliding hymn to urban glow. The closing title track “Die Mensch-Maschine” returns to the central idea: voice and sequencer locked together in a mantra about the interchangeable roles of man, tool and product.

Instrumentally, the album showcases Kraftwerk at full control-room strength. Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider steer banks of analogue synths and vocoders; Karl Bartos and Wolfgang Flür handle electronic drums and sequencer programming, tightening the grid until every hit and blip locks into an aerodynamic groove. The production is dry, spacious and deliberately artificial, favouring precise transients and sharply separated frequency bands over the warmth or ambience of rock recording. This sound design is mirrored visually by the now-classic cover: the group in red shirts and black ties, posed against a bold constructivist layout inspired by El Lissitzky, as if they were both factory workers and their own promotional posters.

In retrospect, Die Mensch-Maschine reads like a hinge between experimental electronic music and the pop and club cultures that would follow. Its melodies and drum patterns seeded countless later developments: synth-pop’s elegance, electro’s machine funk, techno’s linear propulsion, even the icy glamour of certain strands of new wave and post-punk. Yet its lasting power lies less in historical influence than in the completeness of its world. Within half an hour, Kraftwerk sketch a city of robots, models, satellites and glowing signs that still feels strangely contemporary, a place where the distinction between human and device has blurred into a single, efficient rhythm. Listening today, the album’s polished surfaces and controlled pulses feel less like retro futurism than a calm, catchy report from the future we now inhabit.