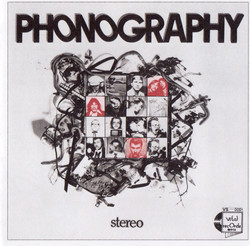

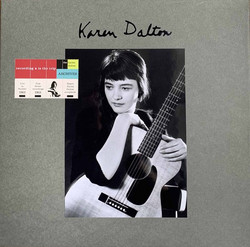

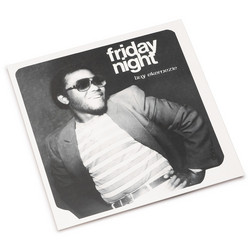

R. Stevie Moore is often called the "godfather of home recording," one of the most recognized artists of the cassette underground, and his influence is particularly felt in the bedroom and hypnagogic pop artists of the post-millennium. Since 1968, he has self-released approximately 400 albums. Born the son of Nashville A-Team bassist Bob Moore, Moore grew up in the 1960s listening to the Beatles, the Beach Boys, the Mothers of Invention, and Jimi Hendrix. In his teens, he acquired access to a reel-to-reel stereo tape deck and began recording as a one-man band in his parents' home. Since 1968, Moore had been recording full-length albums on reel-to-reel tape in his parents' basement in Tennessee, but it was not until 1976's Phonography that any of his recordings were issued on a record label.

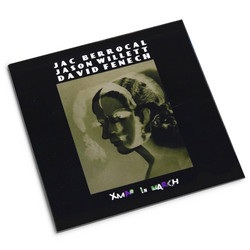

Hearing Aid represents a sustained archaeological dig through Moore's vast cassette archive. The album was originally compiled by Jason Willett for Megaphone Records as a CD in 1996, but complications prevented its release. In 2011, Moore walked into Willett's record shop and declared that Hearing Aid must be done. Willett suggested expanding it to a double album with more songs than originally planned. They succeeded.

The compilation spans 32 songs recorded from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, over 87 minutes of audio. Moore's music sounds like so many different things, yet like no one else. Hearing Aid covers a wide range of variety: pop genius, sublime instrumental country surf, electronic experiments, bizarre spoken-word theater, dark disco rock, field recordings. The end result is not a "greatest hits" collection but rather a diverse sculpture of the early world of R. Stevie Moore.

Matthew Ingram of The Wire wrote that "Moore might not have been the first rock musician to go entirely solo, recording every part from drums to guitar... However, he was the first to explicitly aestheticize the home recording process itself... making him the great-grandfather of lo-fi." Yet Moore himself has always resisted the lo-fi designation. As he explained in Tape Op, "I've constantly been talked about as being lo-fi. Yeah, I'm the grandfather of home taping and lo-fi, but that's not really what it's about. It's the content—it's the variety."

The tracks on Hearing Aid demonstrate that range. There are perfect pop miniatures that could have been hit singles in an alternate universe where radio programmers valued invention over formula. There are instrumental excursions into surf and country that reveal Moore's Nashville roots filtered through a psychedelic lens. There are avant-garde experiments that place him alongside the most radical sonic investigators of his generation. And there are strange interludes—field recordings, spoken-word fragments, sonic jokes—that function as punctuation marks in an ongoing sound diary.

Stewart Mason of AllMusic summarized Moore's body of work as a "one of a kind" mixture of "classic pop influences, arty experimentalism, idiosyncratic lyrics, wild stylistic left turns, and homemade rough edges." However, "entire generations of lo-fi enthusiasts and indie trailblazers, from Guided by Voices to the Apples in Stereo, owe much to [his] pioneering in the field." 95% of Hearing Aid has never appeared before on vinyl. For decades, these recordings circulated only through Moore's cassette club, a mail-order operation he launched in 1982 that made him one of the first musicians to sell directly to fans without industry intermediaries. The double LP format allows these songs to exist as more than digital files or degraded cassette dubs—they become physical artifacts, evidence of one man's determination to document everything, to let nothing escape.

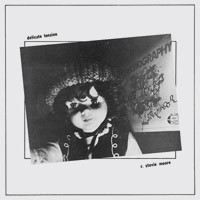

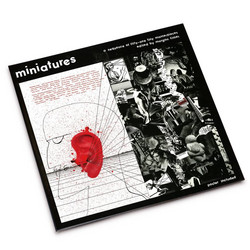

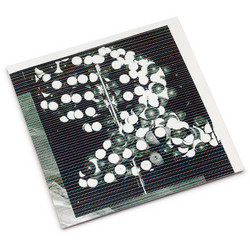

Released in a deluxe gatefold sleeve featuring 284 images of Moore, Hearing Aid functions as both introduction and deep dive, entry point and rabbit hole. This is where DIY begins—not as aesthetic choice or marketing strategy, but as necessity, obsession, a way of being in the world through sound.