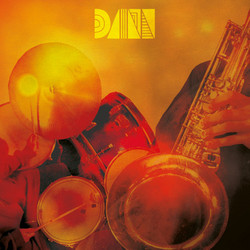

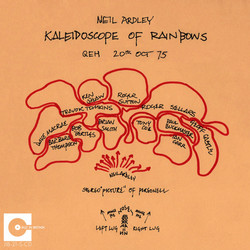

*Limited edition of 500 copies.* British jazz is at a crossroads. The orchestral jazz-rock experiments of the late 1960s and early 1970s are losing momentum. Fusion is going electric and commercial. The old certainties are dissolving. Into this moment, Neil Ardley releases Kaleidoscope of Rainbows - an album that looks backward and forward simultaneously, functioning as both summation and new beginning. This is unmistakably a trait d'union - a bridge - between the British orchestral jazz-rock heritage Ardley helped establish and "a more confident way of writing," heading clearly toward different directions. The final part of a trilogy that began with Greek Variations (1969) and continued with A Symphony of Amaranths (1971), Kaleidoscope of Rainbows finds Ardley abandoning Western classical references for something more exotic, more challenging, more precisely structured.

The concept is radical in its simplicity: Balinese gamelan scales as foundation for British jazz composition. The pelog, a seven-note gamelan scale, and the slendro, an older, more commonly used five-note scale. Ardley uses these in a variety of note patterns, each unique combination becoming the basis for one of seven 'Rainbow' compositions - "Rainbow 1" through "Rainbow 7." Not as tourist exotica or world music fusion, but as systematic compositional method, a way of generating new harmonic and melodic possibilities. The personnel tells you this isn't some academic exercise. Ian Carr on trumpet - founder of Nucleus, one of British jazz-rock's most important groups, a player who understood how to make composed music swing and improvised music cohere. Paul Buckmaster on cello - arranger and composer known for his work with David Bowie and Miles Davis, someone who could navigate between rock, jazz, and classical worlds without losing his footing. Tony Coe on clarinet - master musician whose tone and phrasing elevated everything he touched.

With players like these, Ardley's gamelan-inspired structures become living, breathing music rather than compositional diagrams. The exotic scales generate unfamiliar intervallic relationships, forcing the soloists to think differently, to find new paths through harmonic territory that doesn't follow Western logic. The result is music that sounds both ancient and futuristic, Eastern and British, composed and spontaneous. The minimalist counterpoint that emerges from this approach points toward where Ardley was heading. Three years later, he'd release Harmony of the Spheres (1979) - that spacey masterpiece where synthesizers and orchestral forces merged into cosmic jazz of the highest order. You can hear it beginning here: the interest in systematic processes, the willingness to let structure generate content, the understanding that repetition and variation could create hypnotic effects previously foreign to British jazz.

Kaleidoscope of Rainbows exists in strange territory - too jazz for classical audiences, too composed for fusion fans, too exotic for mainstream jazz listeners, too serious for the commercial market that British jazz-rock had briefly flirted with. Which is precisely why it matters. Ardley wasn't chasing trends or compromising vision. He was following his compositional instincts wherever they led, trusting that the music itself would justify the journey.