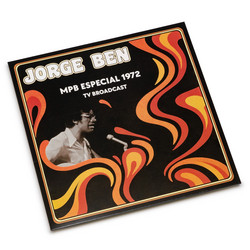

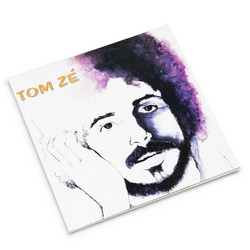

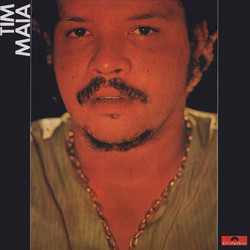

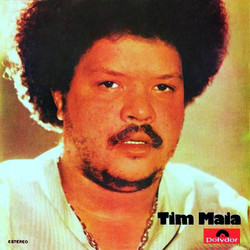

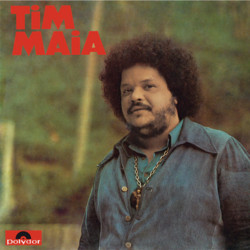

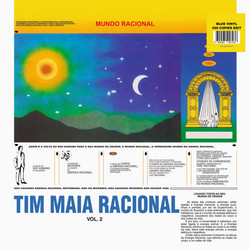

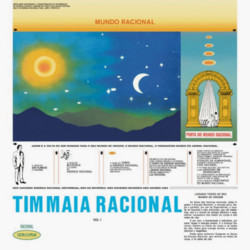

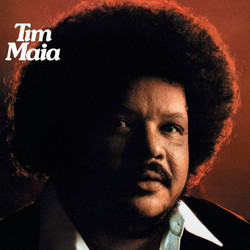

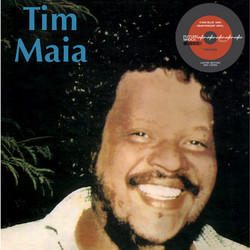

In the early 1970′s, Brazilian popular music was approaching a high water mark of creativity and popularity. Artists like Elis Regina, Chico Buarque and Milton Nascimento were delivering top-shelf Brazilian pop, while tropicalists Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil and Os Mutantes (see World Psychedelic Classics 1) were entertaining the college set with avant-garde fuzz-pop poetry. Enter Tim Maia with a massive cannonball into the pool. It was the only dive Tim knew. Standing just 5’7 (6′ with the Afro) Tim Maia was large, in charge and completely out of control. He was the personification of rock star excess, having lived through five marriages and at least six children, multiple prison sentences, voluminous drug habits and a stint in an UFO obsessed religious cult. Tim is also remembered as a fat, arrogant, overindulgent, barely tolerated, yet beloved man-child who died too young at the age of 55. Sebastiño Rodrigues Maia was born in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, on September 28, 1942. He was the 18th in a family of 19 siblings. At six he started to contribute to the family income by delivering homemade food prepared by his mother, Maria Imaculada Maia. Tim learned to play guitar as a child and was 15 when he formed his first band. They called themselves The Sputniks and were notable for also including Roberto Carlos, a neighborhood pal of Tim’s who would later become one of Brazil’s biggest stars. In 1957, at the age of 17, the singer went to America. He left home with $12 in his pocket and no knowledge of English. He adopted the name ‘Jimmy’ and lied to the immigration authorities, saying that he was a student. Living with distant cousins in Tarrytown, New York, he worked odd jobs and committed petty crimes. Having a prodigious ear he quickly learned to speak, sing and write songs in English. He formed a small vocal group called The Ideals who even recorded one of Tim’s songs, “New Love.” Intent on starting a career in America, Tim never planned on going back to Brazil, but like a badass Forrest Gump, he also had a knack for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In a 1964 early pre-cursor to Spring Break’s modern debauchery, Tim was busted in Daytona, Florida for smoking pot in a stolen car and served six months in prison. U.S. Immigration caught up with him and he was deported. Back in Brazil, Tim told his friends that he hadn’t spoken a word of Portuguese for the last 3 years of his stay in the U.S. Not surprisingly, he was completely out of step with the prevailing mode of MPB and Tropicalia. Eventually he got a huge break when legendary singer Elis Regina fell in love with his song “These Are the Songs” which had been released as a single on the Fermata label. She invited him to sing a duet of it with her in Portuguese and English on her 1970 album “Em Pleno Verño”. This high profile debut forced people to take notice of the unknown singer/songwriter with a big voice, bigger afro and huge ambitions. Soon after, Philips signed Tim to a recording contract. In 1970 his first album spent 24 weeks on the charts, beginning a new chapter in Brazilian music. His close friend, Nelson Motta, who was the A & R rep who signed Tim to the Philips label remembers Tim’s initial impact on the scene: He was something absolutely new. Until then, Brazilian music was divided into nationalist MPB Tropicalia and international rock. All really white and really English. Tim Maia changed the game, introducing modern black music from the U.S. to national pop music, linking funk and baiño, bringing soul closer to bossa nova and opening windows and doors to new forms of music that were not Tropicalist, nor MPB, nor rock n’ roll: they were quintessentially Brazilian. They were Tim Maia. Prior to the 1970′s, the average white, urban Brazilian imagined him or herself living in a harmonious melting pot of European, African and indigenous heritage, but racism, despite being distinctly different than in North America, still permeated Brazilian society. There were no shortages of prominent Afro-Brazilian musicians, singers or composers, but black Brazilians were primarily typecast as nothing more than happy-go-lucky samba singers. Tim wasn’t the first Brazilian artist under the sway of North American black music: Wilson Simonal and Jorge Ben experimented and synthesized different soul and funk rhythms into their styles, but Tim was the first to completely flip the equation, embracing soul and funk music wholeheartedly, adding indigenous Brazilian touches if and when they fit. Tim’s first commercial records showed that a black Brazilian singer could assert his identity with confidence and power. His music helped to build the Black Rio movement, a new Afro-Brazilian music culture influenced by the U.S. civil rights struggle. As a result, Tim Maia’s soul music described a modern Black Brazilian identity that blew the doors off mass culture’s tightly circumscribed role for Afro-Brazilians. More importantly, as Tim basically says in “Let’s Have a Ball Tonight:” ‘Fuck politics! Let’s make love and party!’ According to Nelson Motta, the impact of his music was felt where it mattered the most: on the dance floor and in the bedroom: With his thundering and sultry voice he enchanted and seduced legions of dancers and lovers along his explosive and turbulent career of 40 years. Sweetening and adding velvet touches to his voice, then downing the lights, he crooned his ballads and inspired hot romances and lots of sex, like a tropical Barry White (one of his idols, together with Isaac Hayes and James Brown). Like no other pop star – including most of the best comedians in the land – he made the people laugh. “I don’t burn, I don’t snort, and I don’t drink. My only problem is that sometimes I lie a little.” (Often said with a joint in hand). He was the funniest (and smartest) man in the Brazilian music scene. With hit after hit, he started his brilliant career, cheered by critics and adored by the big audiences, rich and poor, black and white, rockers and bossanovistas as well. A funny thing happened when Tim Maia launched his career in Brazil: he kept on writing and recording songs in English. Every album (all titled Tim Maia with only the copyright years to differentiate) included at least one, if not a few songs in English. Obviously, Tim “Jimmy” Maia’s teenage dreams of international soul success didn’t die when he was deported from the U.S.