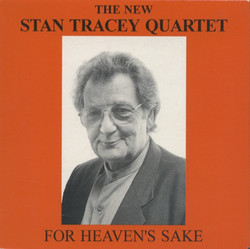

** In process of Stocking. 2021 Stock ** John Fordham It would make an absorbing blindfold test to present a panel of interested listeners with a track from this disc and one from the same pianist's Little Klunk trio session for Decca, 40 years ago, and invite them to decide which one's played by the 71 year-old. Not that the early record didn't sound as fresh, witty and jostling with clamorous harmonies and sidelong melody as Tracey has done for most of his life, but that the later one is, miraculously, fresher still. If there's an obvious difference it's that Tracey, striking out for an identity in the crowded piano-jazz world of the late 1950s, performed originals on Little Klunk and delivers moving tributes to absent heroes and personal guiding spirits like Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk here. But, as always, Stan Tracey is a restlessly exuberant embodiment of the axiom that his role as a jazz artist is to make a song sound, not like itself, but like himself. There's enough evidence of that here to make confirmed Tracey fans stand up and cheer, and unconfirmed ones give the response some serious attention. His work has rarely sounded more positive, expansive, varied and open. 'I could appreciate what was involved in all the rest of bebop piano playing' Tracey said to this writer way back in 1973.

'But it seemed so limited - once you'd got to the way of doing it, you knew what was coming. There was very little opportunity to bring into use the things that the piano can do better than anything else.' If Stan Tracey has devoted his life to a single project in jazz, it's the art of playing total piano - giving all the instrument's inner voicings, percussive effects, orchestra-like shouts, quick horn-like runs and reverberant sliences humming with overtones, an equal place in the rich tapestry of his music. If you want some confirmation, it comes from the opening bars. Listen to Tracey's statement of the theme and then the development of his solo after his propulsive son Clark's hissing cymbal intro to It Don't Mean A Thing - the choppy chords of the counter-melody, the spaces and tantalising silences left against Andy Cleyndert's firm bass walk, the sudden thumping chords, the glittering treble runs, the chord patterns jostling across each other like conversations in a crowded room, ending in a grinning mischievous trill. It's a masterly demonstration of the elusive art of solo development, the knack of spontaneous storytelling described by Lester Young.

But if you leave this tune believing (as you might if you had only heard part of a Stan Tracey gig) that his solo playing is principally a fusion of the methods of a pianist and drummer, the other side of Stan isn't far away. If you meet him, and you find yourself wrong-footed by that reflex irony and deflation of sentiment that many jazz musicians have, you might be surprised by how poignantly and sympathetically he can unfold the mysteries of a good ballad (What's New persuasively confirms it). On a piece like this, Tracey's affection for Ellington and his imaginative variations on Ellington's legacy are in some ways more apparent than in his large-group work. Tracey orchestrates a ballad at the keyboard, envelops it in rich, slurred chords swelling up under silvery melodic fragments, adds ambiguity to it with unexpected modulations of key, and on WHAT'S NEW injects a sudden, peremptory trill that makes you jump, before allowing the song to drift into a mist at the close. One of the big attractions of this session is the variety of the material and the variety of Tracey's handling of it. N O Blues is the kind of mid-tempo funky shuffle he relishes being minimalist in, bouncing off his hustling partners with stabbing chords. Bassist Andy Cleyndert uncannily recalls Percy Heath and the MJQ years ago, in the foxily delayed slurs in his solo, and softly padding melody lines, and there's some urgent hand-drumming from Clark Tracey at the end, which gives the whole episode a little of the classy raunchiness of an Ahmad Jamal trio. Tracey the supreme balladeer is back on Angel Eyes (a delectable balance of patient expansion, and shrewd restraint) and on It Could Happen To You.

What Is This Thing is delivered at a typical Tracey dip, the kind where the pianist's solo clatters by like a passing express train, and Lover's Freeway and Bye-ya furnish other slants on the same infectious skill. But the hardest trick to pull off, particularly for a man who has performed it countless times in his life, is the art of refashioning the best known-known jazz vehicles on the planet, and making them both the tradition's songs, and your own, Stan Tracey does it with both Round Midnight and Body And Soul, the latter being a piece with which he has frequently ended his concerts unaccompanied, even those featuring full orchestras. In Tracey's hands, this classic (which might have been assumed to have yielded up all its jazz secrets to Coleman Hawkins, but which has repeatedly flowered afresh with the right kind of nurture) becomes his own unique mix - of flashes of strutting confidence and sombre reflection, coloured by the pianist's gift of confounding expectation in glitzy runs that stop abruptly as if suddenly sobered by the contradictions of life.

Last year, on the eve of his 70th birthday celebrations, Stan Tracey told me: 'I'm always trying to build on what I've done as a player. Despite that 70th year, I'm always looking for new ideas and I'm determined not to coast.' It doesn't take much listening to this delightful record to appreciate just how effective that determination still is. Special thanks to evan parker whose generosity encouraged me to make this album. - Stan Tracey