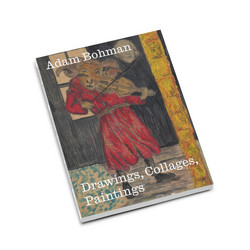

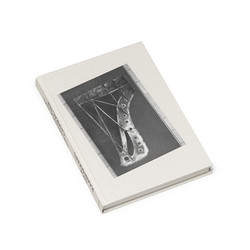

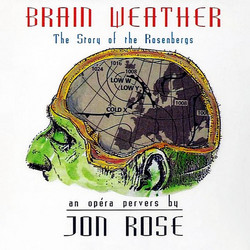

The Pink Violin is the definitive life and non‑times of Dr. Johannes Rosenberg, the greatest Australian composer–violinist who never lived. In this outrageous collaboration, Jon Rose and Rainer Linz construct a fully fledged musical persona from thin air and then subject him to the full weight of institutional “scholarship”: career overviews, theoretical treatises, family trees, language manuals, archival photos, diagrams and footnotes. On the surface, it reads like a serious contribution to Australian 20th‑century music history; beneath that, it’s a precision‑engineered send‑up of how such histories are written, and of the credulity with which they’re often received.

Rosenberg’s imaginary oeuvre becomes the excuse for an entire alternative discipline of violin studies. Readers are treated to “Einsteinian” theories of violins, violin mobiles, violin theorems, violin art forms, cubistic violins and violin installations, as well as a magnificently deranged argument that Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship can be traced to his status as a frustrated, failed violinist. Side chapters and mock appendices push the joke further: Swedish for Violin Playersoffers a language course nobody asked for; a tome on the “Physical Violin” traces the instrument’s supposed role in Olympic Games from 1936 to 1988; and the Rosenberg family tree spins his lineage out into a tangle of improbable relatives and historical coincidences. The whole thing is lavishly illustrated, its diagrams, facsimiles and visual gags lending the project an almost worrying plausibility.

Critics have already grasped the book’s peculiar charm. Umbrella magazine calls it “a wild and heavily illustrated conceit that almost makes you believe it all… a delicious perversion,” while EMI magazine dubs it “a peculiar bird to say the least … wilfully and playfully enigmatic.” The Stradadmits, “…then I found myself laughing uncontrollably and I don’t know why,” and Evos Magazinedelivers the perfectly crooked endorsement: “And I see you’ve got my cheque there, so I’ll give it five stars.”

For performers, composers, students and anyone who has ever sat through an over‑theorised artist talk or waded through dense programme notes, Pink Violin offers both catharsis and a mirror. Rose and Linz’s reformist parody doesn’t just mock: by pushing academic rhetoric and new‑music myth‑making to absurd extremes, it invites readers to reconsider how authority is constructed on the page – and how easily even the most outlandish musical narratives can start to feel true if presented with enough charts, jargon and family trees.