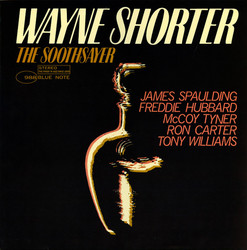

Wayne Shorter

Adam's Apple (LP)

It is unclear whether it was Wayne Shorter’s initial intention to do anything particularly ambitious during the two visits to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in February 1966 that produced Adam’s Apple. Certainly, neither the repertoire—five recently composed Shorter tunes in AABA format and “502 Blues,” by pianist Jimmy Rowles, a hard drinker, as Shorter was at the time (the subtitle denotes the police code for drinking and driving)—nor the treatments contain the radical originality of the five pieces comprising The All-Seeing Eye, recorded four months earlier. Nor is there is a hint of the form-bending improvisational procedures that he, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams were deploying on a nightly basis in the Miles Davis Quintet, for which he’d already composed several consequential pieces—among them “Footprints”—since joining the group in September 1964. Nor does Adam’s Apple contain the vaguely surreal, dreamy, cinematic, parallel universe quality of Etcetera (which would not be heard until 1980) from the previous June.

Rather, Adam’s Apple coheres more closely to such prior vehicles for Shorter’s individualistic tenor saxophone voice as Second Genesis, a VeeJay blues-and-standards swinger from 1960, and JuJu, a kinetic, effervescent session done for Blue Note in August 1964 positioned halfway between the John Coltrane Quartet (the rhythm section are Coltraneans McCoy Tyner, Reggie Workman, and Elvin Jones) and Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, in which Shorter would serve as Musical Director for another month. On Adam’s Apple, even at higher velocities, the ambiance is reflective, with time feels ranging from swing to slow drag to straight-eighth funk to bossa nova. Shorter’s tone is sumptuous in all tempos and registers; Hancock’s voicings and solos epitomize taste placed at the service of imagination; Workman executes the function to perfection and solos with flair; Chambers plays with the blend of surge, touch, and orchestrative nuance that guaranteed that any mid-‘60s Blue Note recording he performed on would be synonymous with excellence.

All of Shorter’s songs on Adam’s Apple have legs, not least his universally covered 6/8 minor blues “Footprints,” here addressed in an in-the-pocket, a la Coltrane manner eight months before Miles Davis stamped it forever with a complex, elegant, tension-and-release treatment that would appear on the 1967 release Miles Smiles. It remains in the book of Shorter’s current quartet with Danilo Perez, John Patitucci, and Brian Blade, as does the Coltrane homage “Chief Crazy Horse,” highlighted by the leader’s soaring, under-control solo flight. Percolating Samba rhythms propel the flow of “El Gaucho,” a wide-open-spaces melody on which Shorter foreshadows his incipient obsession with the sounds of Brazil. On the more introspective side, “Teru” is an exquisite ballad—recently covered by David Binney and Bob Belden—with an Ellington-Strayhorn quality enhanced by Shorter’s vibrato-less reading, which imparts the quality of art song, or an aria.