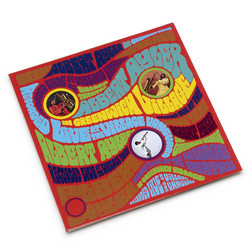

Albert Ayler

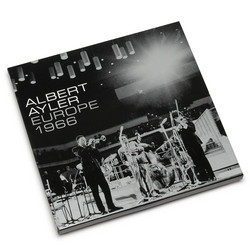

Berlin, Lörrach, Paris & Stockholm - Revisited (2CD)

In the fall of 1966, Albert Ayler embarked on a European tour with his current quintet. For the first time, the four recorded concerts previously issued by Hat are presented here in one package, in chronological order. The group included his brother, trumpeter Donald Ayler, with whom he worked for years but the other three members were relative newcomers to the ensemble. Beaver Harris, who had played and recorded with Archie Shepp and Marion Brown, took over the drum duties from Ronald Shannon Jackson, while these events seem to have been bassist Bill Folwell’s earliest captured performances (he would go on to record with the rock band, Ars Nova and in a few sessions with various blues musicians). But the most intriguing addition to the group is without question the violinist, Michael Sampson, who helps evolve hitherto unheard textures in Ayler’s music. Classically trained, Sampson drifted toward avant-garde ideas, working with The Living Theatre performance ensemble in Rome and, in late 1965, joining Ornette Coleman onstage during a concert in Amsterdam. He relocated back to New York later that year, soon visiting Living Theatre member Peter Bergman in Cleveland, where he attended a club performance by Ayler. As he had done with Coleman, Sampson approached Ayler, who invited him to sit in and who was immediately captured by his sound, asking him to rejoin the group for their upcoming booking at Slugs in New York City (years later issued as “At Slug’s Saloon”, volumes 1 & 2 on several labels). Within a couple of years, however, which included some work with John Handy, Sampson left the jazz world, concentrating instead on Western classical music.

The difference in Ayler’s group sound can be heard immediately from the beginning of the material assemble herein, ‘Truth Is Marching In’, from the Berlin set. The texture is lighter, even creamy, with a wide sonic space opened between violin and tenor saxophone in terms of timbre and the contrast between the ethereality of the strings and the earthbound (though upwards striving), guttural nature of Ayler’s horn. The piece also serves to introduce another salient feature of this point in Ayler’s development: whereas many musicians paid lip service to the collectivist, non-hierarchical ideas formulated by Coleman and others, to a larger than normal degree, this grouping often manifests as a solo- less ensemble, all the members working simultaneous variations on the hymn-like or marching themes originated by Ayler. Solos occur, but they feel more emergent from the general rewing than cyclic or routine.

Sampson gets a few turns more or less on his own and the rest, especially Donal Ayler, are heard soloing now and then, generally briefly, but the brothers are more often found reinforcing the basic melodic lines like a persistent choir. It’s often been said that Ayler’s playing recalls his roots in the African-American church but this appears not only in his own sounds but also in the “congregational” aspect of his co-musicians, collectively reinforcing and elaborating upon the relative handful of melodies in his repertoire. In Lörrach, the date which evinces a more standard amount of solo time, the reading of ‘Bells’ seems to allude to British Isles influence, the strings (both Sampson and Folwell, the latter spending a good portion in all of these sets playing arco), in the role of pipes. The Berlin set seems especially energetic and imaginative, with the strings engaging in a fairly lengthy and probing duet during ‘Omega (Is the Alpha)’ and the intriguing ‘Infinite Spirit/Japan’, the latter perhaps verging on a clichéd imagining of traditional Japanese music but nonetheless affecting. In Paris, on the opening ‘Ghosts’, the tenor and violin seem to inhabit alternate universes, Ayler playing and elaborating on the theme, Sampson up in the ether, flitting and swooping like an escaped songbird—it’s a rather amazing sequence.

‘Spiritual Rebirth/Light in Darkness/Infinite Spirit’ begins pensively, its approach less sure-footed than many of its gospel-drenched brethren, and touches on slightly Spanish sounding material, interrupted briefly by a strutting march before unfolding into more expansive space, more celebratory than martial. Finally, there is ‘All/Our Prayer/Holy Family’, the initial section heard for the first time in this set of concerts. Like ‘Japan’, one has the sense of a vaguely imagined turn on some notion of Native American song, complete with (uncredited) vocalizing. It’s a little disorienting- ing, but soon segues into the by now familiar ‘Our Prayer’, soulful and comforting, Donald’s trumpet beseeching, his plea answered by the rousing, down-home theme of ‘Holy Family’. - Brian Olewnick, December 5th, 2020