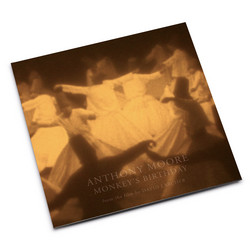

Meredith Monk

Book Of Days

Meredith Monk is generally described as an avant-garde artist of many talents. Of her many talents there is no question, but what exactly makes her “avant-garde”? The Random House Dictionary defines the term as meaning “of or pertaining to the experimental treatment of artistic, musical, or literary material.” This raises another question: What does it mean to be experimental? The same dictionary gives us: “founded on…an act or operation for the purpose of discovering something unknown or of testing a principle.” At the risk of reading too much into semantics, I would venture to say that Monk is anything but avant-garde, for she is interested neither in discovering the unknown nor in proving suppositions. Rather, she reveals that which has been obscured by, as well as changed by, history. She interrogates the subjective over the empirical and its effect on the flow of intercontinental relations. Thus do we get Book of Days (1988), a marriage of music and moving images that covers such broad yet related topics as nuclear holocaust, AIDS, eschatological wonder and trepidation, and the cyclical nature of time. The idea for Book of Days came to Monk one afternoon in the summer of 1984, when she was overcome by a black-and-white vision of a young Jewish girl in a medieval street. This same figure would become the locus for much of the film’s traumatic crossfire, amid which the girl has visions of her own, only for her they are of a grave and violent future. She soon encounters a madwoman (played by Monk herself) and discovers in her that one kindred spirit in a world headed for annihilation.

The film’s soundtrack was later reworked into the studio version recorded here and scored for 12 voices, synthesizer, cello, bagpipe, hurdy-gurdy, piano, and hammered dulcimer. The music of Book of Days also wavers between past and future, rendering the present all but graspable. These temporal concepts are accordingly reflected in the arrangements of each itinerant section. A triptych of monodies (“Early Morning Melody,” “Afternoon Melodies,” and “Eva’s Song”) mark the passage of the sun in the sky, the contrast of dark and light. This diurnal atmosphere is further underscored with the hurdy-gurdy-infused “Dusk” and the smooth braid of vocal beauty that is “Evening.” This chronology culminates with the delicate “Dream,” an all-too-brief reprieve from the threat of Armageddon, before opening into “Dawn.” The five scattered pieces that make up “Travellers” constitute time as diaspora, each its own lilting pseudo-canon of both hummed and open-mouthed syllables. The fourth section, subtitled “Churchyard Entertainment,” fleshes out the thematic core of the entire work in its most fully realized form. In a similar vein, “Fields/Clouds” unfurls an ethereal carpet of synthesized organ for a procession of contrapuntal voices, with Monk soaring above all like a predatory bird riding a thermal. Time’s fragility is expressed in “Plague,” a rhythmic chant of whispers, hisses, tisks, and heavy breathing: the universe in a pair of lungs. Encompassing all of this is “Madwoman’s Vision,” a masterpiece of composition and performance that flits nimbly from creaking aphasia to elegiac commentary. The album fades to black with “Cave Song,” alluding perhaps to Plato’s shadows and the illusory nature of our attachments.

The markedly instrumental approach to the human voice embodied by this ensemble lends itself beautifully to the subject matter at hand. In choosing to eschew words entirely, Monk peers more deeply into the oracular interior of her music. Relying on nascent phonemes such as “na” and “la” in lieu of recognizable vocabularies, she complicates the linearity of her effected nostalgia. Book of Days is all the more haunting for reducing that nostalgia to a liquid state and scooping up as much of it as possible before it seeps out of sight through those very cracks where her music is born.