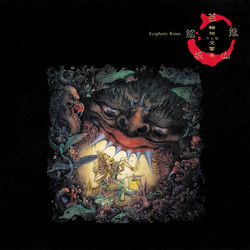

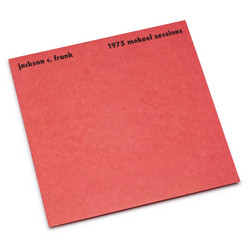

Legendary Texan artist Terry Allen occupies a unique position straddling the frontiers of country music and visual art; he has worked with everyone from Guy Clark to David Byrne to Lucinda Williams, and his artwork resides in museums worldwide. Widely celebrated as a masterpiece—arguably the greatest concept album of all time—his spare, haunting 1975 debut LP Juarez is a violent, fractured tale of the chthonic American Southwest and borderlands. Produced in collaboration with the artist and meticulously remastered from the original analog tapes, this is the definitive edition of the art-country classic: the first reissue on vinyl; the first to feature the originally intended artwork (including the art prints that accompanied the first edition); and the first to contextualize the album within Allen’s fifty-year art practice.

Juarez is not just an album, at least not in any ordinary sense of the word. Songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen describes it instead as a “haunting.” For nearly five decades, Juarez has served as the elusive, enigmatic axis mundi of his artistic and musical practices. Never discrete or static, the Juarez mythos continually accretes a growing constellation of new meanings, mutations, and manifestations, defying linearity and finality, appearing as drawings, constructions, songs, prints, installations, texts, a screenplay, a musical theater piece (co-written with David Byrne), a one-woman stage play, and an NPR radio play (both starring his wife, the actor and writer Jo Harvey Allen).

Herein Juarez inhabits the ur-corrido sonic artifact, a cycle of fifteen songs and recited poems—austere, atmospheric, cinematic—as recorded over the course of a few mornings at San Francisco’s venerable Wally Heider Studio in 1974. Its stately, minimal arrangements—Allen on piano and vocals, with guitarists Peter Kaukonen (Link Wray, Jefferson Airplane, Black Kangaroo) and Greg Douglas (Van Morrison, Peter Rowan,Steve Miller Band)—belie its sinister, mongrel strangeness, its anxious hilarity, its casual alloy of spirituality and profanity, its uncanny enormity as story. Originally released in 1975 by print workshop Landfall Press in an edition of fifty, with a set of nine lithographs (reproduced in full for the first time in the reissue’s extensive book), the record encompasses both conceptual corrido and cosmic cartography, song and séance, at once hermetic and wide-open. In these fifty-two minutes, geographies, climates, and spectral bodies collide and elide, dragged and fate-flung across the parched Southwest, over mesas and arroyos and through the abraded lens of colonial history, throwing dust, shedding blood, and further blurring the already arbitrary, and forever contested, boundaries of the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

As described in one of the periodic narrative “dialogue” interludes spoken by Allen, Juarez recounts a deceptively “simple story”: a bleak journey, told in nonlinear terms, from Southern California through Colorado and into the Texas-Mexico borderlands. Like many cross-country road trips, it’s as harrowing as it is humorous, often within the margins of a single song or even an isolated line. The action revolves around two couples and their fateful—or arbitrary—murderous meeting in Cortez, Colorado. Sailor, on leave from the Navy, meets Spanish Alice, a prostitute, in a Tijuana bar; they get married and honeymoon in a mountain trailer park in Cortez. Meanwhile, on a crime spree detour, pachuco antihero Jabo and the witchy “rock-writer” Chic Blundie drive North from L.A. to Cortez on their way South to Jabo’s hometown of Ciudad Juarez (until recently the homicide capital of the world). Only one couple emerges from the bloody trailer, escaping across the New Mexican desert to Juarez, where they part, assuming (or absorbing?) new identities.

Terry Allen is no stranger to the ramifications of border-crossing—it’s something he’s been doing both literally and figuratively, geographically and professionally, for his entire adult life. A native West Texan who now lives inSanta Fe, New Mexico—he hails from Lubbock, also home to Buddy Holly, Waylon Jennings, and the Flatlanders—Allen occupies a unique position straddling the disparate worlds of country music and visual art. We’re not sure that you could say the same about anyone else, ever, and certainly not with the same level of aplomb, acclaim, and success—not to mention the same biting, self-effacing sense of humor about it all.

Allen’s artwork resides in the collections of the Met, MoMA, the Hirshhorn, and Los Angeles’ MoCA and LACMA, among many other institutions, and has been exhibited internationally at Documenta and the São Paolo, Paris, Sydney, and Whitney Biennales. You can encounter his public commissions across the U.S. He is the recipient of Guggenheim and NEA Fellowships. In the realm of music, in addition to several projects with the aforementioned Byrne, Allen has likewise collaborated closely with Guy Clark, Lloyd Maines (pedal steel master, producer, and father of the Dixie Chicks’ Natalie), and the Flatlanders (Butch Hancock, Joe Ely, andJimmie Dale Gilmore). His songs have been covered, recorded, and championed by the likes of Dave Alvin,Laurie Anderson, Bobby Bare, Ryan Bingham, Don Everly, Jason Isbell, Robert Earl Keen, Little Feat, Ricky Nelson, Peter Rowan, Doug Sahm, Sturgill Simpson, and Lucinda Williams. Forty years later, Juarez is widely regarded as Allen’s first masterpiece, timelessly relevant, resonating with works of film and literature as much as other music, recalling the existential violence of Terrence Malick’s Badlands(1973) and informing successors like David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990), Cormac McCarthy’s Border Trilogy(1992-98), and Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 (2004). Paradise of Bachelors will reissue Terry Allen’s critically acclaimed 1979 double album Lubbock (on everything), the follow-up to Juarez, later in 2016.