Himukalt

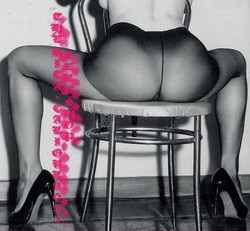

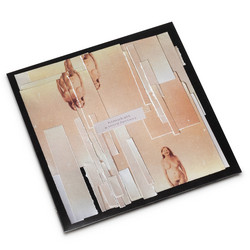

Last Wish (LP)

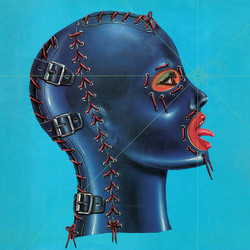

Last Wish is one of those records where Himukalt turns autobiography into something sharper, stranger and more confrontational than confession. Framed as fiction but sparked by the collapse of a sexless relationship, the album channels not heartbreak but a more corrosive residue: contempt, pity, unresolved rage. The narrator admits that by the end “I didn’t love her; I just felt pity for her,” yet the anger remained, and Last Wish becomes the space where that anger is stretched, tested, and held as long as possible. Noise here is not a backdrop but the chosen medium for sustained hostility – a way of seeing how far emotional voltage can be carried before it burns through the circuitry.

Structurally, the album is built around two extended pieces, which gives the whole thing the feel of a single monologue broken into movements rather than a conventional track list. That length is crucial: it lets the narrative stew and seethe rather than simply flare up and disappear. Explicit spoken word sections slip between erotic detail, recrimination and self‑scrutiny; they are neither pornographic nor redemptive, but something more awkwardly human, full of hesitation, repetition and sudden sharpness. Around and under the voice, dark, heavy electronics spool out in long bands – low‑end pressure, corroded tones, searing high‑frequency layers – creating a chamber where the listener has nowhere to stand that isn’t implicated in what’s being said.

Part of the album’s pull lies in how it handles contrast. There are passages of velvety, almost narcotic atmosphere where synth drift and soft reverb give the illusion of safety, only for deadpan, mechanical percussion or sheets of blistering harsh noise to intrude like intrusive thoughts. The sensual and the ascetic keep trading places: textures that might be “pleasurable” in another context become abrasive when paired with certain words; bare, almost clinical sequences suddenly feel charged because of what the narration has just revealed. This tension between body and distance – between wanting and wanting to wound – is exactly what gives Last Wish its uneasy erotic‑electronics edge.

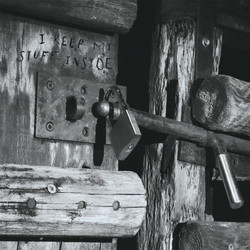

The original cassette release framed the work as “a pained monologue of futile love” and “a truly devastating document of erotic‑electronics,” and that feels right not as a slogan but as a description of its strange social effect. Listening to Last Wish, there’s a sense of being made to overhear something that was never meant to leave a bedroom, a therapist’s office or an unsent email folder. That “private becoming public” is where the album’s power and discomfort reside: the woman who sparked the story has already been reduced to “barely a ghost” in the artist’s erotic memory, but the anger she left behind has been fixed to tape, replayed and re‑embodied every time the album runs. What remains is not a portrait of her but a self‑portrait in distortion – desire curdled into noise, and noise sharpened into a weapon that finally turns back on its wielder just as much as on its supposed target.