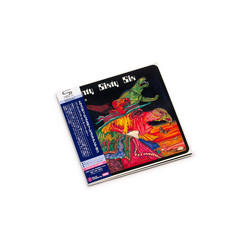

King Crimson

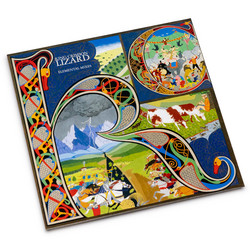

Lizard (CD+DVD)

* This release comes in a 2×digipack format in a slipcase with new sleeve notes by Robert Fripp and King Crimson biographer Sid Smith along with rare photos and archive material* Released in December 1970, King Crimson's third studio album, Lizard, is often viewed as an outlier in the pioneering British prog outfit's nearly half-century discography. It's not easily grouped with 1969's stunning In the Court of the Crimson King debut and 1970 follow-up In the Wake of Poseidon, and along with 1971's Islands it's considered a transitional release on the band's path toward the relative stability of the Larks' Tongues in Aspic (1973), Starless and Bible Black (1974), and Red (1974) trilogy. Plus, the Lizard sessions were difficult and the core group lineup acrimoniously collapsed immediately afterward, as bandleader/guitarist Robert Fripp, with lyricist Peter Sinfield, continued brave efforts to save King Crimson from disintegrating as the group's lengthy history was just getting underway. Even Fripp himself wasn't a big Lizard fan until he reportedly "heard the Music in the music" when listening to Steven Wilson's 2009 40th anniversary remix. Yet there are plenty of Crimson followers who place Lizard at the very apex of the group's recorded legacy -- and with good reason. Seamlessly blending rock, jazz, and classical in a way that few albums have successfully achieved, Lizard is epic, intimate, cacophonic, and subtle by turn -- and infused with the dark moods first heard when "21st Century Schizoid Man" and "Epitaph" reached listeners' ears the previous year.

Opener "Cirkus" is a cavalcade of menace, with vocalist Gordon Haskell intoning or declaiming Sinfield's phantasmagorical words over a kaleidoscopic musical backdrop, the song's ripping buzzsaw refrain alternating with warped funhouse jazz prominently featuring keyboardist Keith Tippett and saxophonist Mel Collins. "Indoor Games" is comparatively whimsical, with Collins' blurty sax almost comically up-front in the mix and crisp ensemble interplay in the middle section, while the singsongy "Happy Family" finds Sinfield's lyrics obliquely addressing the Beatles' breakup and "Lady of the Dancing Water" revisits the gentle terrain of "I Talk to the Wind" and "Cadence and Cascade." But the side-long multi-part title suite astounds the most. Guest Jon Anderson's choirboy vocals open "Lizard" with a feint toward the light and airy, but Haskell's brassy chorus suggests ritualistic precursors to dark goings-on. The suite then enters its "Bolero" movement, marked by Robin Miller's beautiful oboe and Fripp's swelling Mellotron, with a jazz interlude showcasing Collins, cornetist Mark Charig, trombonist Nick Evans, and a jagged and explosive Tippett, collectively free and even ebullient in their interplay but never fully breaking away from drummer Andy McCulloch's background rat-a-tat snare that foreshadows the howling maelstrom of "The Battle of Glass Tears." After the smoke clears, Fripp's sustained guitar notes cut through the funereal aftermath, dissolving into silence before the swirling "Big Top" coda brings the album full circle, suggesting Lizard's dark journey on an endless loop accelerating into the future. In 2016, lineup changes made it possible to include selections from this album in King Crimson's career-spanning live concerts, and with all the spectacular music on display, more than one audience member could be heard saying, "I came for Lizard."