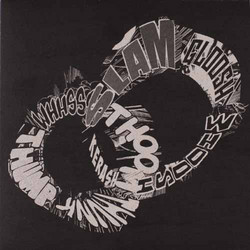

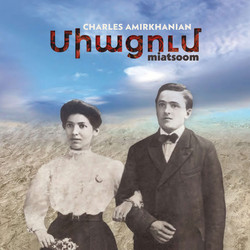

Charles Amirkhanian

Loudspeakers (2 CD)

Charles Amirkhanian (b. 1945) can be regarded as a central figure in American music, and on several fronts. As a composer, he's been pervasively innovative in two genres: text-sound pieces, in which he can draw engaging rhythmic processes from wacky word assemblages such as 'rainbow chug bandit' and 'church car rubber baby buggy bumper'; and natural-sound electronic pieces which go far beyond the usual confines of musique concrète to create long, poetic sound narratives poised between collage and sonic landscape. Amirkhanian's text-sound pieces often begin with a quasi-minimalist basis in repetition, but their processes are playful and even humorous rather than strict. His electronic landscapes (including all the ones here) occasionally include repetitive elements, but are more poetic, intuitive in their form and often impressionistic in their effect.

Several of his earlier commercial recordings have showcased the text-sound pieces; the present two-disc set is a welcome compendium of his sound landscapes. We might characterize the whole as three tone poems preceded by a set of ten etudes. The set of ten pieces, Pianola (Pas de mains) (1997-2000) -- the subtitle is French for 'no hands' -- stems from Amirkhanian's long fascination with the player piano, or pianola -- the self-playing piano, and is a whimsical set of essays based on the sound and techniques of the player piano.

The remaining three works [Im Frühling (1989-90), Son of Metropolis San Francisco (1997), Loudspeakers (for Morton Feldman) (1988-90)] might be characterized as extended love poems, so affectionately do they portray their respective subjects: spring, San Francisco, and the composer Morton Feldman. These pieces were composed using the Synclavier, an electronic sampling keyboard first developed at Dartmouth in the late 1970s, for which Amirkhanian has written many of the most ambitious works. What links all these pieces is a creative ambiguity of genre, a delight in shifting back and forth between elements whose sources can be recognized and those whose can't. The pacing, at least in the latter three works, is leisurely, and somewhere between ambient and symphonic: One can listen to them as atmosphere, yet a sense of overall dramatic shaping is not absent. Though we listen to them through loudspeakers, it seems problematic to pigeonhole Amirkhanian as an 'electronic' composer.

The music, restful and noisy at once, is too playful for that, and too natural -- and elicits a listening mode that brings no other composer to mind.

![data-cosm [n°1]](https://cdn.soundohm.com/data/products/2026-02/ikedda-data-cosm-1-jpeg.jpeg.250.jpg)