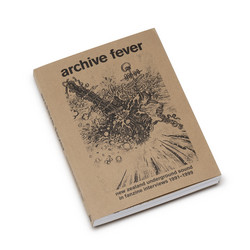

"Music with Roots in the Aether" is a series of interviews with seven composers who seemed to me (Robert Ashley) when I conceived the piece-and who still seem to me twenty-five years later-to be among the most important, influential and active members of the so-called avant-garde movement in American music, a movement that had its origins in the work of and in the stories about composers who started hearing things in a new way at least fifty years ago.

There is, of course, our indebtedness to Europe. In spite of the obvious influence of the music of other cultures in our avant-garde, our music is still in a European-American tradition-probably because the American musical culture is so young and because so many American composers have European roots. Even the extraordinary influence of African-American music in the avant-garde is through the experience of African-Americans-in-America. The story of African-American music and its shameful lack of recognition has been discussed in many other places. The European avant-garde is known about from unusual sources (if it is known at all): rumors, personal relationships with composers and such-certainly not (in the period up to 1975) from available scores or performances in the United States. But it is clearly different. So, what I wanted to isolate in "Music with Roots in the Aether" is the peculiarity of the American side of the story. I could not presume to know everything because my own experience is so limited. Thus, "Music with Roots in the Aether" is just about a special area in music, its problems, its sore spots and its triumphs.

The interviews themselves are casual and desultory. They had to be, because of the manner in which they were made. They were made in front of a video camera, with the rule that there would be no video editing. So, the composers are just talking. Then, the conversations are edited for print to take out as much of the conversational looseness as possible. I hoped to get in the transcriptions a free floating collection of remarks. Such a plan carries no argument with it. It makes, at best, a kind of splintered portrait of a few people whose lives and whose work I admire. It is almost coincidental to this intent that these same people have contributed individually and collectively to so much of what is the shape of serious music in 1999, not just in America now, but wherever American music is heard.

These are my friends. I love their music. They are among the most important people in my life. The portrait is shattered because I could not make it whole.

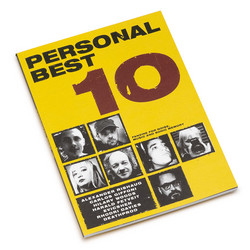

In a moment of rash ambition (I thought the book would be published immediately), when the interviews had just been finished, I asked younger composers-composers of the "next" generation-to write a set of articles that would complement the interviews. No rules were established about style. A young person writes about an older colleague. The article is addressed to the community of musicians among whom this music is most important. So, the articles are peculiarly technical and idiosyncratic, using the language and the attitudes that composers use among themselves. The idea is that each article is part of the portrait, too.

I would disavow, right off, the notion that any of these younger composers were chosen because their musical ideas are derived from or are in any way imitations of what they find in the work of their older colleagues. I picked the younger composers because I knew them and their work personally and, thus, because I knew of their familiarity with and respect for the body of work they were to write about. I asked them to be specifically technical, because at the time when this part of the project was alive there was virtually nothing in print about the technique of the new music. This was, again, twenty-five years ago.

Unfortunately, nothing much has changed since. Four of the subject composers, Philip Glass, Alvin Lucier, Pauline Oliveros and Roger Reynolds, have published books about their ideas. The composer Thomas DeLio, whom I did not know at the time, has since published perceptive articles about some of these ideas, and those articles have been collected in two very useful books. Other books, in particular by Kyle Gann and William Duckworth, are very good. The aging but still lively journalist of the performance avant-garde in general, John Rockwell, wrote a book about living composers, and it is a valuable book, but his point of view is sociological, largely stressing the tragedy of the composer’s situation; it is sympathetic, kindly, but rarely technical to any degree.

In the meantime the twenty-five years have passed for all of us. The composers who are the subject of "Music with Roots in the Aether" have continued with their work, accumulating reputation in varying degrees of notoriety and fame. I think they are all still more or less in a good mood in spite of the charms of approaching old age. The younger composers, who so generously gave of their time and energy in their writing, have gone forward with their personal styles and careers and, I am proud to say, have begun to challenge the reputations of the elders. All over the United States, in academic music departments, in organizations outside of academia and even in so-called "popular" music, the ideas have continued to spread.

My impression, circa 1999, is that the peculiarly "American" aspects of the music I intended to portray have come even more to the fore than was easily identified when I began working on the project. And my impression is that the European avant-garde is headed in a different direction now. One should be happy about this, I believe. The notion of an "international style" thankfully disappeared somewhere in the middle fifties. So, this is not a tract in the cause of "American" music. One hopes for as much variety as possible. It is just a portrait.

My ambition to publish this writing twenty-five years ago was "rash" because, considering the vitality of the music and its growing influence, I thought somebody in the music publishing business might be interested, if only for historical reasons. Finally, I got an offer. The money involved, had I gone through with the contract, might have covered telephone and taxi expenses. It could hardly inspire one to drop everything and finish the project. So, this preamble is, in one way, an apology to the younger composers, who actually believed me that the book would be published and who finished articles that involved a lot of time away from their own work, effort in an area that is not their "calling," extensive research and the ever lurking threat of being condemned for taking part in the project to begin with. It is also an apology to the composers of my generation who took part in the larger, opera-for-television project of the same name, "Music with Roots in the Aether," from which the interviews are extracted. The opera has not made it to "major" television, yet. Thousands of these composers’ fans and new music lovers in general have seen the video tapes in closed-circuit presentations and in local cable broadcasts, and to that extent the collaborations were fruitful, but the idea in its larger version is still at loose ends, and that failure on my part is one of the typical failures of large scale projects in the avant garde in America today.

The book is also rashly "spotty." None of us could pretend to professional quality in our writing or (in the interviews) in our spontaneous remarks about the techniques of our music. But that combination is too rare to wait around for. When there is no information and information is needed, you can’t worry too much about whether the book is a great book in its execution. The purpose is to make available some kind of record of the thinking of the composers and the ideas of the music. My advice to the reader is: when the going gets a little heavy with too much jargon and sentences that don’t quite work, just jump to some other place in the book. Treat it as an accurate but not too serious reference book. It is jammed with information and pretty lax about rules. Or treat it as a message, not quite decipherable, from some alien culture. This second approach would correspond to the treatment of the music itself (and the composers) and the ideas you would get about the music from reading professional "critics"-that is, specifically, journalists, who are (sadly) committed "professionals" (that is, hacks) and who have almost universally treated the music as though it were from an alien culture. And we know from, say, Stephen Spielberg, how dangerous aliens are thought to be by serious-minded people.

Time out here, before I get in too much trouble with "journalists," some few of whom may actually review this book. We are all "journalists" in an era of absolute horror: worldwide suffering and starvation, totalitarian governments everywhere, the guilt of our atrocities heavy on us all and the not-unrealistic threat of a nuclear disaster-which will render all thoughts of the problems of music and culture obsolete-and the realization that none of us, individually, can do much about the situation. Little wonder that we are divided against ourselves, that we find fault everywhere, that nothing satisfies us, that we try to escape, especially in our ideas about culture and music, to a more graceful (or, at least, less ominous) past. More than anyone, probably, composers and artists in general know that their ideas would be taken seriously, if the ideas were to be expressed, for instance, in the medium of terrorism or in the medium of politics in general. So, there is too much to be "done." Our specialization and isolation makes us obsessed with continuing specialization.

Alvin Lucier suggested that, if we are to expect our contemporaries in, say, literature, to know about and appreciate our music, we should be expected to read what they write as artists. I don’t know how far he has gotten, but it looks like an impossible job to me. There is definitely a glut, and what is impossible to achieve, individually, in the real-world of politics is equally impossible to achieve in the world of the arts. Nobody knows anything. Rich and cultured people are almost unanimously as ignorant of the contemporary musical arts as the proverbial "truck-driver." Philip Glass complained that the situation for the American composer can never improve because the only thing Americans are interested in is television and sports. That got me, because the only things I am interested in (aside from music), as a composer, are television and sports: television, because like music I can have it in my home; and sports, because like in contemporary music nobody gets killed. (In the music of previous generations it is indisputable that killing was a big deal. "Music with Roots in the Aether" tries to suggest that we have outlived that idea.) There are fleeting signs of "improvement." Television has taken up music as one of its minor subjects. Unfortunately, since television is still in the hands of "television" people and is largely "educational" in intent (what records to buy or what you don’t know about the past), a lot of music-for-television is filled with violence of all sorts, as if to continue the idea of killing in our kids.

But maybe that will pass. Maybe the pressure of public opinion will make directors start insisting on using real bullets, and then, finally, tiring of the endless stream of non-celebrity faces, the public will start listening to music and start seeing it dramatized as one of the unimaginable achievements of humanity. I wouldn’t bet on it, but it’s our only hope.

Sports, obviously, doesn’t need much of a defence from me. It has produced almost without exception the most humane-seeming, the most articulate, humorous and professionally generous celebrities of our time. No wonder we like sports. I observe with just a little envy that persons who only a few decades ago worked virtually as slaves (and who didn’t make any better a living than the avant-garde does now) have collectively made a place for what they love as a way of life and have come out of that struggle with a respect for each other that is continually expressed in the most glowing and touching terms.

Alvin Lucier loves sports. Terry Riley is reputed to have been a pretty good sandlot baseball player. David Behrman is indifferent, I guess. I don’t know about the opinions of Gordon Mumma or Pauline Oliveros. So much for sports.

Television is a different matter. I am, frankly, obsessed with television, not because I enjoy seeing people symbolically murdered and the unreality of the hero escaping at "point-blank" range while the bad guy gets it at Lee Harvey Oswald distance. At any indication of impending violence I change channels with the dexterity of "Blue" Gene Tyranny at the keyboard. But the multi-camera (multi-viewpoint) technology of television is so deeply related to the multi-viewpoint essence of music that, looking forward to the day when all television is "live," in my mind music and television are the perfect couple.

The history of "Music with Roots in the Aether" is so complicated and paradoxical for me as its author-so pathetically typical of the difficulties faced by composers in America in undertaking large scale projects and seeing them through to completion-that I have doubts that I have in any way succeeded. "Music with Roots in the Aether" is certainly just one of thousands of big ideas, dreams, desires, plans that composers have had since the beginnings of serious music in America that never really get finished, because there are no mechanisms of support in our society, yet, that the composer can look to for help.

I am not talking just about money, though that always appears to be the main problem. I am talking about the more complex-and unsolvable by any single person-problem of how to get the work produced and made available to the audience for which it is intended. That this problem can have disastrous personal effects on the composer’s intentions even as the idea is being conceived must be obvious, but I can’t go into that. The argument is simply that assuming the composer to be superhuman in optimism and good will-or just plain nuts-to the degree that the project is actually begun and the composer keeps believing in it and working on it, there comes a point inevitably when it must be recognized that the next obstacle is insurmountable. The sun is setting and the day is over. End of project. Depression. Chemicals. Suicide. Get a job selling something. Who cares?

Every composer knows this and knows all the reasons why. Spare the reader a long list of complaints against publishers and the more up-to-date media. The reason is that we are, apparently, too young and raw as a "people" to know how to make it work. And so our serious music, the audience for which is demonstrably enormous in number but spread all across a huge continent, is in a disastrous disarray, divided against itself, attacked on all sides by an almost universally stupid and ignorant "critical" press and dispirited to the point where one has to wonder how the music continues to grow at all. But like a sort of misunderstood teenager of great intelligence and promise, it goes on anyway, sometimes blinded in tears, often in trouble with all conventions of good behavior and without much hope, but destined to grow simply according to the laws of nature.