Frederic Rzewski

Nonsequiturs: Writings & Lectures on Improvisation, Composition and Interpretation (Book)

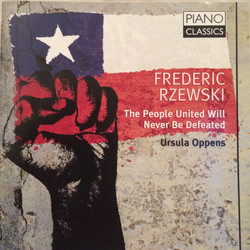

English-German edition, 576 pages (!) collection of writings about ideas concerning music by American composer Frederic Rzewski (April 13, 1938 – June 26, 2021) considered to be one of the most important American composer-pianists of his time. Rzewski’s anti-establishment thinking stood at the center of his music-making throughout his life. It was evident in the experimental, agitprop improvisations he created in the 1960s with the ensemble Musica Elettronica Viva; in “Coming Together,” the Minimalist classic inspired by the Attica prison uprising; and a vast catalog of solo piano works, several of which have become cornerstones of the modern repertoire. His approach was epitomized in his best-known piece, “The People United Will Never Be Defeated!,” an expansive and virtuosic set of 36 variations on a Chilean protest song. Composed for the pianist Ursula Oppens in 1975, the piece, an hour long, is a torrent of inventive and unusual techniques — the pianist whistles, shouts and slams the lid of the instrument — and has been compared to canonic works like Beethoven’s “Diabelli Variations” and Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.”

After graduating from Phillips Academy in Massachusetts, Rzewski studied music at Harvard with the tonal composers Randall Thompson and Walter Piston. He earned his master’s at Princeton. In 1960 and 1961, he studied with Luigi Dallapiccola in Florence on a Fulbright scholarship. In Europe, he gained renown performing music by luminaries like Karlheinz Stockhausen and, after a stint in Berlin studying with Elliott Carter, settled in Rome.

The European avant-garde had fallen under the sway of John Cage’s experimentalism, and Mr. Rzewski wrote heady music like his “Composition for Two Players,” an unconventional score that he once interpreted by placing sheets of glass on the strings of a Steinway.

In 1966, he and the composer Alvin Curran assembled a group of musicians, including the electronic composer Richard Teitelbaum, to perform in the crypt of a church in Rome. The collective became Musica Elettronica Viva, an act that used homemade electronics setups for visceral improvisations. Mr. Rzewski, for instance, scraped and drummed on a piece of glass that had been cut into the shape of a piano, to which he had attached a microphone. (“By the grace of God, we didn’t get electrocuted,” he later said.)

Rejecting the dense, modernist scores of his previous academic environs, Mr. Rzewski became preoccupied with spontaneity.

“The sublime mingled freely with the base,” he once wrote of “Spacecraft,” one of the sets of trippy instructions that guided Musica Elettronica Viva’s performances. “Climaxes of exhausting intensity alternated with Tibetan drones, ecstatic trances gave way to demonic seizures in rapid succession.” The collective gave more than 100 performances across Europe in the late 1960s, and its raucous concerts drew increasingly politicized listeners. As students agitated, the group joined in, inviting audiences to play with them in anarchic improvisations — a kind of avant-garde Summer of Love. The group also performed in factories and prisons. “The most important thing was the connection of community and the political,” the composer and scholar George E. Lewis, who performed in later iterations of the collective, said in a recent interview. “Music gave people choices and options, and collectively creating music together allowed everyone to rethink their situations.”

In 1971, Rzewski moved to New York and resumed a more routine concert life, playing recitals of new music and joining the downtown improvisation scene. And he began to bring his politics to bear on works he created alone. “It is fairly clear that the storms of the ’60s have momentarily subsided, giving way to a period of reflection,” he wrote that year. First was “Les Moutons de Panurge,” which asks an ensemble to play a tricky, ever-shifting 65-note melody. “Stay together as long as you can, but if you get lost, stay lost,” the score impishly indicates.

Then came “Coming Together,” in which a speaker recites a letter written by Sam Melville, a leader of the 1971 Attica prison uprising, over a chugging, minimalist bass line as instrumentalists contribute quasi-improvised interjections. Mr. Rzewski would occasionally perform “Coming Together” himself, playing and speaking simultaneously. The music is at once calculated and urgent; Rzewski described the Attica rebellion, in which 43 people died, as an “atrocity that demanded of every responsible person that had any power to cry out, that he cry out.” Its many interpreters have included the performance artist Steve Ben Israel, the composer-performer Julius Eastman and Angela Davis, the professor and political activist. During this period Rzewski became involved in the Musicians Action Collective, a coalition that organized benefit concerts for United Farm Workers, a defense fund for Attica inmates and the Chilean solidarity movement.

He was soon drawn to the song “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,” which had become an anthem for the Chilean resistance through performances by the exiled group Inti-Illimani. Written by Sergio Ortega and Quilapayún, the song served as the basis for Mr. Rzewski’s set of variations, commissioned for the United States Bicentennial and first performed by Ms. Oppens at the Kennedy Center in Washington in 1976.

“People always say, ‘Well, how can music be political if it has no text?’ Mr. Rzewski told an interviewer that year. “It doesn’t require a text. It does, however, require some kind of consciousness of the active relationship between music and the rest of the world.”

Returning to Europe in the late 1970s, Rzewski split his time between Italy and Liège, where he was a professor at the Conservatoire Royal de Musique until his death, and he made regular visits to the United States to perform and teach.