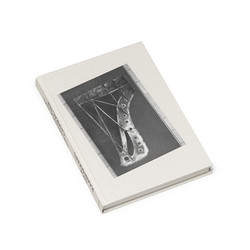

Robert Ashley

Outside of Time - Ideas about Music (Book)

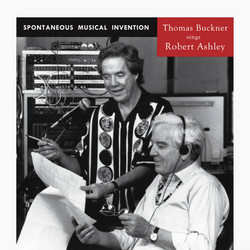

English-German Edition, 655 pages (!) collection of writings about ideas concerning music by American composer Robert Ashley. For nearly forty-five years, composer robert Ashley has pursued his vision of opera in the face of near complete indifference from the American mainstream culture industry. Ashley’s experience parallels that of other American indepen-dent avant-garde figures such as Terry Riley, Alvin lucier, and Pauline Oliveros. like these composers, Ashley uses notation only to the extent that it conveys his ideas to a longtime “band” of collaborators (which includes singers Jacqueline Humbert, Sam Ashley, Thomas Buckner, and Joan La Barbara, along with engi-neer/mixer Tom Hamilton). like Oliveros, Ashley is also keenly interested in performance as ritual; for the past three decades he has composed operas that rely upon the inflections and rhythms of American english and are set against the backdrop of a largely static “electronic orchestra.” Although much of Ashley’s work is conceived for television, only the seven-part Perfect Lives (1977–83) has been completely realized in its intended medium, and it has never been shown on American networks. Now, as Ashley enters his eighties, a european musicolo-gist—ralf Dietrich—has taken on the task of gathering Ashley’s essays, sketches of pieces, and program notes into one volume.

This bilingual collection—with verso pages in english and recto pages in ger -man—is divided into four parts, the first three of which are arranged in roughly reverse chronological order. ordering the collection in this way arguably serves two purposes: First, it helps familiarize readers who might be unfamiliar with Ash-ley’s work with an overview of his aesthetic and how it was shaped by changes in technology, collaborators, and economic realities. second, by laying out the various guiding “threads” through Ashley’s career, one is better able to follow the divergent strands as they stretch back into his past work. The first section, “Towards a New kind of opera,” begins with a detailed “musical autobiography”—Ashley’s recollections of changes in the American contemporary music scene over his long career—and is followed by a series of essays that establish the groundwork for Ashley’s brand of music theater. one distinctive strand running through Ashley’s varied compositional career is the drone, appearing in early pieces such as the In Memoriam series from 1963 as a “reference sonority,” and also found in the recent operas in the form of a sustained harmonic backdrop or “cloud” that the singers use to establish the modality and inflection (contour) of their singing. A second unifying factor is a preoccupation with numbers and predetermined “formulas,” revealed in great-est detail in Ashley’s discussion of the individual “templates” in Perfect Lives. in this work, each episode has a characteristic visual structure (composition of images, distinctive colors, times of day, camera angles / movements, and so on), which also occurs in a fractal-like self-similar fashion within each episode—in other words, each episode is itself made up of seven sections that follow the same procession through the templates, and some sections of some episodes are further subdivided into seven subsections. The thorough descriptions of Ashley’s working methods—illustrated with fragments from his sketches and production notebooks—are especially valuable, since almost none of this music is published in conventional score format.

The second section, “Discovering the musicality of speech: mills College,” focuses on the works composed during Ashley’s tenure at mills College in oak-land, California, from 1969 to 1978, a period during which Ashley “stopped composing” in order to “make music.” (This is a fine distinction—Ashley did in fact create several works during this period, most notably the nearly one-hour In Sara, Mencken, Christ and Beethoven There Were Men and Women (1972–73), as well as perform with the sonic Arts union, a collective that also included composers Alvin Lucier, David Behrman and Gordon Mumma.) originally brought to mills to build an electronic music studio, which soon developed into a public access studio, Ashley soon drafted a plan for a master’s level degree program in elec-tronic music and recording media (one of the first in the nation), leading to the creation of the Center for Contemporary music at mills College. Ashley taught composition and served as director of the Center, but became dissatisfied with the work: “Teaching musical composition is impossible, i think. . . . i thought of myself as a ‘provider.’ Whatever anybody thought they needed for their music, i tried to provide it. This was a convenient way out” (316). Today, he acknowledges the period at mills for having changed his music profoundly: “i became thoroughly immune to scores. Nobody working at the Center wrote scores. Circuit diagrams, yes. Computer programs, yes. Tacti-cal plans for making a concert, yes. scores, no” (316). one fascinating piece from this period is “The remote boundary illusion,” one of four “hypothetical computer-controlled installations” called Illusion Models (1970). This piece uses sensors to locate a listener ’s position in a darkened room and interactively change the sound mix in such a way that the listener cannot determine the size of the room as he or she negotiates the space. Though “hypothetical” in 1970, this aural-spatial illusion uncannily anticipated virtual-reality technological breakthroughs of the 1990s.

The book’s third section comprises a number of essays and sketches from Ash-ley’s involvement in the oNCe Festival (1961–66) and oNCe group (1964–71). unfortunately, many of the oNCe pieces were documented either sparsely or not at all. Nonetheless, of particular interest are the pieces Combination Wedding and Funeral (1964), which directly inspired the “Church” episode of Perfect Lives,and The Trial of Anna Opie Wehrer and Unknown Accomplices for Crimes Against Humanity (1968), whose “interrogation dialogue” format foreshadows much of Ashley’s later work. There are also a number of interesting “conceptual pieces” from this period, verbal scores showing the influence of Fluxus figures such as la monte Young, george brecht, and Dick Higgins. These include Rock Soup(1972), an outdoor performance piece for two or more keyboards powered by automobile batteries and triggering various automobile horns, and Spaghetti for a Large Number of People (1973), which outlines the steps for a spaghetti-and-salad potluck dinner.

The book’s substantial final section collects the program and liner notes for all of Ashley’s major works, from The Fox (1957) to Ashley’s 2006 opera Concrete; a list of works (complete up to 2009) rounds out the volume. many of the writings in this volume have been previously published, but are hard to find, having first appeared in small limited-press european journals or program notes from Ashley’s live performances. Ashley’s newer contribu-tions made specifically for this volume are thoughtful and penetrating; in one particularly striking passage, he describes the new-music recital as creating an artificial museum culture while stifling any prospects of offering the specta-tor a transformational ritual experience: “it could have been juggling or a live porno act. Whatever it is, you are not a part of it. You have been a watcher. . . . You have simply been distracted from what is outside. You do not have more of a musical life. Your life is not more musical” (56). The fragments of sketches and notebooks are essential for those who wish to understand how these performances are realized, or to revive long-unperformed works. in as-sembling this compendium, ralf Dietrich has obviously benefited from a close and long-term cooperation of his subject; one hopes that, in turn, Ashley will benefit from the additional exposure that such a collection will bring to his impressively original body of work. (Kevin Holm-Hudson, University of Kentucky)