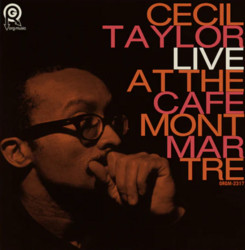

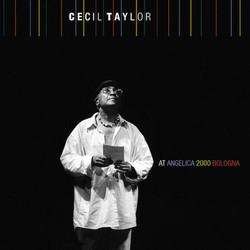

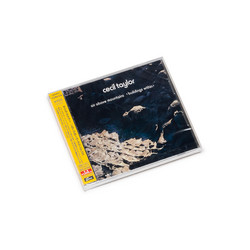

*2023 stock* 'The chief attraction of this album is an almost 50 minute, previously unreleased solo performance by Taylor given at New York University in November 1976 as part of the Bösendorfer Festival, a benefit series for the Kitchen performance centre. His previous solo recital that year had been in August at Moosham Castle in the Lungau region of Salzburg during an open-air festival, subsequently released as Air Above Mountains (Buildings Within) (Enja, 1977). Taylor had come across a Bösendorfer piano in the basement of the University of Wisconsin while he was artist-in-residence in 1971 but the Alpine concert was his first recorded performance playing the instrument, which may have provided connections with the New York festival three months later. Built in Vienna, a Bösendorfer remained his favoured piano with the Imperial Grand model extending the usual 88 keys to 97 to provide a full 8 octaves, the somewhat spooky sounding extra keys in the bass coloured entirely black and covered by a removable panel on earlier builds. Even when the lowest notes are not used – and it’s unclear how often Taylor employed them – more importantly those additional strings, combined with the huge frame and uniquely tailored body, add a sympathetic resonance and rich undertones producing what he described as a mellow lower register.

As noted in Ekkehard Jost’s illuminating essay, Instant Composing as Body Language, “for Taylor, the type and quality of his instrument is an essential component of his technique; it comprises, along with the technique itself, a cornerstone of his musical message” which is one of the reasons why, where possible, he asked for long rehearsal sessions with the piano before a concert. A Bösendorfer is known for having distinct tonal qualities in its different registers, unlike the more integrated sound of other pianos, something that would have appealed to Taylor’s stratified conception of the instrument and its potential for multiple voicings. In this performance he explores a vivid palette with relish as his hands dance furiously at opposite ends of the keyboard. Warm layers of veiled resonance open and close the recital, fulsome chords sound out in the bass and contrast with dizzying, toccata-like passages that gain a crystalline sparkle as they race into the upper register.

Beneath the sheer exuberance of his playing however, is a cool intelligence and a technical understanding that was hard won. Take rhythm for example – for Taylor this is not a matter of an underpinning regularity but something that becomes a generative power in its own right, a motion from within and inextricably linked to his motifs. Typically, the smallest unit dictates the pulse of the material, his rapid fingerwork multiplying small values rather than dividing larger ones so that rhythm turns into an energy source having a particular density and momentum. Basic patterns remain recognisable, but he augments or contracts disrupting their flow as they spread outward: splintered, juxtaposed, intertwined, caught in the pull of competing forces and giving his music its distinctive vitality.' - Colin Green