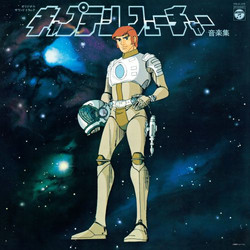

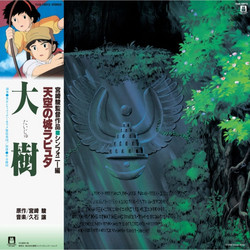

** 2026 Stock ** Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is where Joe Hisaishi’s partnership with Hayao Miyazaki truly ignites. Released in 1984, two years before the founding of Studio Ghibli but retrospectively folded into its canon, the film demanded a score that could handle war, environmental collapse, insect deities and a pacifist heroine without collapsing into cliché. Hisaishi responded with a multi‑tiered body of music: an Image Album drafted from Miyazaki’s manga, a full original soundtrack for the completed film and a later Symphonic Suite, each expanding the same core material in different directions. Together they map the sonic DNA not only of Nausicaä but of much of Ghibli’s later emotional vocabulary.

The Image Album (Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind: Image Album – Tori no Hito), composed before animation began, works like a concept album based on the comic: eleven pieces including “Wind Legend,” “To the Far Place (Nausicaä’s Theme),” “Meve,” “Corroded Sea,” “Return of the Demon Army,” “Distant Days” and “Bird People,” each sketching characters and environments in advance. The finished film soundtrack – often released under the subtitle Towards the Faraway Land – condenses and refines these ideas into thirteen cues, from the “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind – Opening” through “Stampede of the Ohmu,” “The Valley of the Wind,” “The Invasion of Kushana,” “In the Sea of Corruption,” “The Resurrection of the Giant Warrior,” “Nausicaä Requiem” and the ending song “The Bird Man.” Unlike many later Ghibli scores, this original OST leans heavily on early‑’80s electronics—synths, drum machines and processed textures—alongside acoustic instruments, giving the film a slightly surreal, hybrid energy that mirrors its fusion of medieval and futuristic imagery.

Key motives run through all versions. “Wind Legend” / the Opening theme is built around a bold, modal melody that immediately establishes the scale of the story, while “Valley of the Wind” offers a gentler, pastoral counterpart for Nausicaä’s home community. Action cues like “Stampede of the Ohmu,” “Battle” and “The Battle Between Mehve and Corvette” stitch together urgent ostinati, sharp brass and chattering percussion, embodying both human conflict and the terrifying force of the insect hordes. By contrast, “In the Sea of Corruption” and “In A Corrupt Sea” are dense, slowly shifting sound worlds, using dissonance, echo and unusual timbres to evoke a toxic ecosystem that is also mysterious and sacred.

The score’s emotional pivot comes with “Nausicaä Requiem,” where a child’s voice (sung in the film by a young girl, on record by actress Narumi Yasuda in some editions) floats over a simple chord progression, combining innocence and mourning in a way that has become emblematic of Hisaishi’s approach. The ending song “The Bird Man” ties things off with a more explicitly pop‑structured theme, but its melody and harmony are tightly bound to the rest of the score, making it feel like a resolution rather than an add‑on. These elements are later expanded and re‑orchestrated in the Symphonic Suite – Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind / Orchestra, recorded with a 50‑piece ensemble and reshaped into longer movements such as “The Legend of the Wind,” “Battle,” “To the Land of Faraway…,” “Sea of Corruption,” “Mehve,” “The Giant Warrior – The Tolmekian Army – Her Highness Kushana,” “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind,” “The Distant Days” and “The Road to the Valley.”

Recent Japanese and international vinyl editions make all three strands available: the Image Album, the Original Soundtrack and the Symphonic Suite, each with restored artwork (often using Miyazaki’s manga watercolours or poster designs), booklets and OBI strips. They highlight how unusually rich Nausicaä’s musical ecosystem is: early synth‑driven sketches, film‑ready hybrids and full orchestral re‑imaginings, all anchored by the same handful of themes. More than forty years on, Hisaishi’s work for Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind still feels singular – a score that treats environmental catastrophe, political violence and spiritual rebirth with a seriousness and melodic clarity that helped define what “anime music” could be, long before that term had much meaning outside Japan.