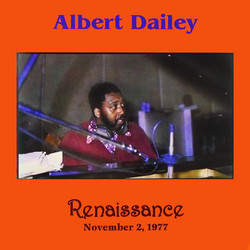

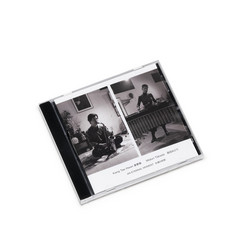

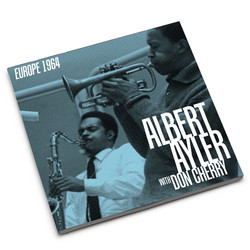

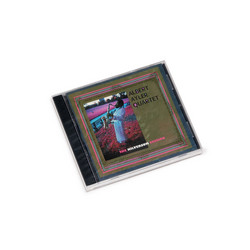

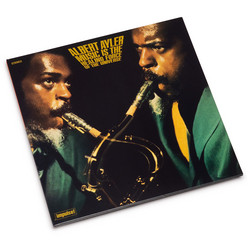

Albert Ayler

Spirits To Ghosts Revisited

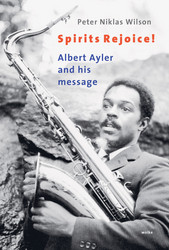

"The mystery of Albert Ayler's musical legacy - as much as that of his still-unexplained death in 1970 - remains today, more than 54 years after these explosive, enigmatic studio recordings were made in early and late 1964, a source of conjecture and controversy. Primarily because his stunningly powerful projection, unorthodox technique, and unique vision resisted the typical methods of description and analysis, critics and scholars (the major exception, of course, being Ekkehard Jost) have sought to illuminate or, on the other hand, discredit Ayler's extraordinarily original creations largely through speculation and metaphor.

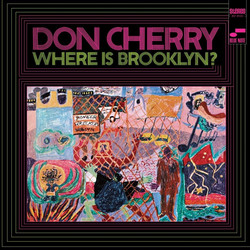

It's hard to blame them. Although it did not emerge from a vacuum, there were no obvious immediate precedents to prepare listeners for Ayler's idiosyncratic, iconoclastic improvisational concept. Consider even the most progressive of his peers. Ornette Coleman had issued his most radical statement, the album Free Jazz, in 1960, but except for three live recordings and the 1965 "soundtrack" to the film Chappaqua Suite he provided nothing of note between March 1961 and September 1966. John Coltrane would not record A Love Supreme until December 1964, and in the period before this released music that was no more advanced - and in some cases much more conservative - than that which he performed at the Village Vanguard in 1961. In 1962 and '63, Sonny Rollins was performing the most adventurous music of his career, freely improvised escapades in tandem with the everpresent trumpeter Don Cherry, but except for one edited RCA album, the bulk of this amazing music was not heard until years later. Archie Shepp had worked with Cecil Taylor and the New York Contemporary Five, but was still in the process of developing a cogent approach to the consequences of freedom. Eric Dolphy, after suggesting an alternative direction to total freedom alongside Coltrane and Charles Mingus, died in June 1964.

A few clues may be gleaned from Ayler's initial efforts once out of the Army. A pair of haphazardly recorded albums of standards from Stockholm in October 1962 (First Recordings, Vol. 1 & 2) and a third from Copenhagen three months later (My Name is Albert Ayler) revealed a puzzlingly inchoate perspective - wickedly abused melodies, a seemingly random wandering through keys, and a willfully distorted saxophone tone ranging from pinched squeals to hoarse guttural braying - which seems even more disoriented due to the conventional support of the Scandinavian rhythm sections. What makes these albums unsettling and spellbinding is Ayler's intuitive albeit disruptive lyricism and deadly serious nature - there is no sense of Sonny Rollins' spontaneous wit or constructivist irony to be heard, none of Coltrane's relentless "Chasin' the Trane" style of thematic elaboration, or Dolphy's harmonic and rhythmic angularity. Ayler's demeanor is neither nihilistic disdain nor absurdist whimsy; the tunes are simply vehicles for expressive - indeed, sometimes painfully exaggerated - gestures of abstracted sound.

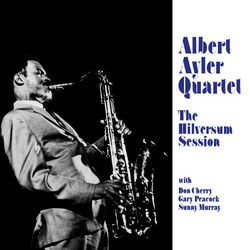

Nevertheless, the leap from there to the music on this disc (as well as his Trio recordings of 1964 Prophecy and Spiritual Unity with Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray, which will for the first time be released in one complete edition by Hat Hut Records under agreement with the Albert Ayler Estate) in just over a year is a large one, and accounts for the mature, uncompromising, uninhibited, revelatory Ayler canon. He sounds strengthened in his resolve to exploit

Thus the unfettered cries were associated with field hollers; the ensemble's simultaneous exhortations became New Orleans-style polyphony; Ayler's wide saxophone vibrato found a link to Sidney Bechet; episodes of intense abandon signified political and social unrest; the wailing ballads were heard as hymns and invocations to a spiritual transcendence; and so on. But this is not to suggest that these are imagined or inconsequential explanations; Ayler's own statements and song titles may or may not provide validation. Nevertheless, they do tend to obscure a deeper sense of the originality and courage of Ayler's conception in distinctly musical terms. And although in his final years the idea of pure sound values as emotional weight and communicative essence. Hence the abandoning of familiar standards in favor of his own simpler, "folk-derived" themes. Yet the new expressive vocabulary - the hyperextreme wails, growls, and whimpers, devoid of quotations or references to familiar musical experiences - that he and his cohorts sustained while disposing of conventional tonality and phrasing in song form seemed so alienating that interpretations required a conventional, if metaphorical rather than musical, logic.

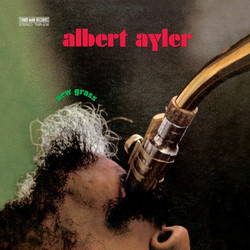

Ayler shifted his approach to a simplified rock and r&b style, either for commercial or communicative considerations, the expressive qualities of his example have been carried on and extended (or unfortunately in many cases diluted), remaining highly influential among free jazz practitioners today - so much so, that we can no longer hear this music with the amazement of those 1964 listeners. And yet it has lost none of its impact."- Art Lange