For fans of acoustic guitar music, James Blackshaw's The Cloud of Unknowing is a gift that's long overdue. Blackshaw's fourth album gracefully glides over the same sonic ground that his contemporaries generally tread with reverential obedience or dilettante tactics. Growing into his prodigious own at the relatively young age of 25, Blackshaw has finessed his 12-string acoustic guitar into a veritable solo symphony that's as schooled in uncommon beauty as it is in complex 20th century composition. But don't fear the esoterics: For everyone else, The Cloud of Unknowing is the gem no one expected to find. Blackshaw writes high drama into instrumental music with subtlety and charm, speaking on sentiments and stories without requiring a single lyric (or, most of the time, any accompaniment at all). A rare intersection of genre advancement and general accessibility, The Cloud of Unknowing is one of the true masterpieces of its own heralded realm. The title The Cloud of Unknowing is lifted from an anonymous 14th century text that articulated a mystical view of Christianity which asserts that God can be better met through a continuum of experience and love than through absolute knowledge. Fittingly, the five pieces here capitalize on dramatic push and pull, alternately joyous and foreboding 12-string figures that are constantly reabsorbed into a web of sheer movement and energy. Despite his age, Blackshaw accomplishes this through profound musical erudition: Closer "Stained Glass Windows" nods to microtonality, climbing up and down an arch in the tiniest intervals, much like Rhys Chatham's gorgeous, glacial work with 400 electric guitars on A Crimson Grail. During "The Mirror Speaks", disparate melodies collide, interlock and crisscross, bending and pushing one another up or down. In his final years, Claude Debussy could pin such lines against one another with a piano in much the same way, but Blackshaw is an Englishman born nearly a decade after Bert Jansch left Pentangle and thriving in a time during which folk has found renewed currency. So here, he assimilates those past masters and, prospering from what he's learned from them, laces one technique to another. Part of Blackshaw's success stems from his confidence. He's a beneficent host to one of the few non-technical ideals that united the great early minimalists: He fully inhabits an idea, allows it to build, and expires only when it is ready. The Cloud of Unknowing opens and closes with 11 and 15 minutes pieces, yet these long forms are as approachable as the best four-minute pop songs. Their complex frames bear lucid motifs through brisk movement, guiding the listener through thousands of notes from 10 fingers and 12 strings with purpose. Such perfect commitment is new to this album. Earlier non-guitar excursions embedded in Blackshaw's work felt slightly apologetic or indecisive. An excessive tampoura-and-cymbala drone overran the best bits of last year's O True Believer, and a disc-closing track with heavy percussion and organ provided a simple, sour end. Blackshaw was tempering his extremist tendencies then. On The Cloud, though, Blackshaw seems fully settled, engaging his pieces and ideas with the unflinching belief of Tony Conrad in 1964 or Steve Reich in 1965. "Running to the Ghost" augments guitar with violin and glockenspiel, but those auxiliary parts are mere bells and strings highlighting how much sound Blackshaw can fit in one lithe motion. Indeed, it's his rumbling bass line (his tuning for this track starts in B) supporting a nimble, mid-range melody and the strings that weave between its notes. The glockenspiel teases from above. The only non-guitar piece is a wandering four-minute electronic token. It's long enough to serve as an intermission but short enough to feel more like a pause than a distraction. And that's a good thing. On an album where movement, experience, and persistence mean everything, it's best to let Blackshaw's 12-string momentum have as much space as it wants. The Cloud of Unknowing carves out a new, peerless space altogether-- one that puts Blackshaw at the top of his class.

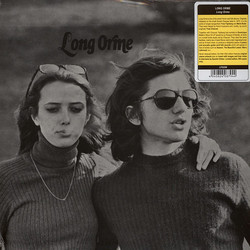

Details

Cat. number: TSQ 1967CD

Year: 2010