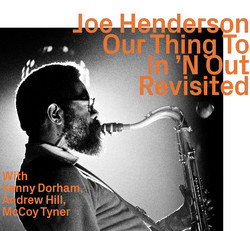

Evaluating Henderson’s gift on tenor inevitably raises comparisons with his contemporaries John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Wayne Shorter. And what sets Henderson apart from the others might be his accessibility. No one could touch Coltrane’s harmonic depth bordering on spirituality. Rollins’ lusty, colossal power. Or the otherworldly compositional idiosyncrasies of Shorter. But Henderson’s playing made the musicians who came after him feel as though he had paved a path they could follow.

As for us listeners, Henderson expressed everything he wanted by always playing the tune. Control and tranquility on ballads like “Serenity.” Burningly feverish on “In ‘N Out.” Playful and offbeat on the Monk-like “Isotope.” He was reliably explosive when playing hard bop, fresh and disarming when he chose to play more free, soulful and familiar delving into things with a more Latin tinge.

In his field of view and arms embrace were musicians hewing to sensitive and respectful interpretations, as well as players whose instincts were to the extremes of rhythm, register, tempo, and emotion. There isn’t just one box where Joe Henderson landed. And there was another aspect to his playing. Not only had you never heard what he was doing before. Because of his devotion to spontaneous invention, you would never hear it again.

As an ensemble player, he was the ultimate listener. Inevitably, his solos began as a commentary or reflection of the solo before his. He might start quite humbly, building in intensity, evolving a run that, despite rhythmic byways, harmonic leaps, and occasional flurries of impossibly quick notes, felt highly developed and coherent, as though he had chosen to make his statement the last word.