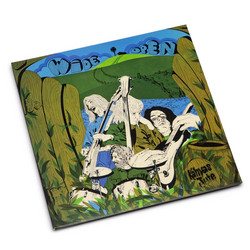

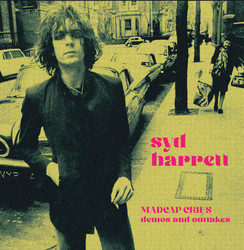

** 2025 stock ** The Madcap Laughs is the debut solo album by Syd Barrett, recorded after his departure from Pink Floyd in 1968 and released on Harvest in January 1970 as a fragile, uncanny coda to the 60s. Its recording history is notoriously chequered: sessions begin in 1968 with producer Peter Jenner, restart in April–July 1969 with EMI’s Malcolm Jones, and are finally shepherded to completion by former bandmates David Gilmour and Roger Waters, with Barrett himself also credited as producer. That relay of hands is audible in the record’s texture - some tracks are almost brutally bare voice-and-guitar takes, others are fleshed out with bass, drums and Soft Machine overdubs - yet a single, unmistakable sensibility holds it together.

From the opening “Terrapin,” Barrett’s love of American blues is filtered through a private, slightly tilted lens: loping rhythms, simple chord cycles, lyrics that veer from direct address to surreal non sequitur. Songs like “Love You” and “Here I Go” are deceptively jaunty, all music-hall swing and wordy, almost whimsical rhymes, but small harmonic wrong turns and slippages in timing let melancholy seep through the cracks. At the other extreme sit pieces such as “Dark Globe,” “Long Gone,” “Feel” and “If It’s in You,” which feel like exposed nerves - performances where phrasing falters, pitches wobble and yet the sense of a real-time, unfiltered emotional plea makes them some of the most affecting recordings of his career. “Golden Hair,” adapted from a James Joyce poem, drifts by like a brief transmission from another room, while “Octopus” compresses Barrett’s Lewis Carroll streak into a dizzy, hooky fragment that became the album’s lone single.

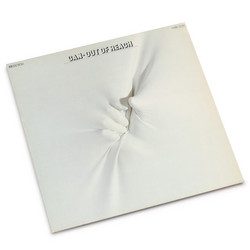

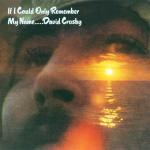

The supporting cast and process add further layers to the myth. On three tracks (“Love You,” “No Good Trying,” “Clowns and Jugglers”), members of Soft Machine - Robert Wyatt, Hugh Hopper and Mike Ratledge - overdub drums, bass and keyboards, trying to wrap Barrett’s loose performances without ironing out their volatility. Malcolm Jones later recalled that playing with him meant “following him, not playing with him,” musicians often a beat behind as they tried to anticipate sudden structural shifts. When Gilmour and Waters take over, they choose not to re-record the core takes but to mix and sequence the existing material quickly, finishing most of the album in a couple of days and leaving in false starts and cracked notes that a more conservative production would have erased. The iconic cover, shot by Mick Rock in Barrett’s Earl’s Court flat with its orange-and-blue striped floor and vase of daffodils, has since become a visual shorthand for this period: domestic space turned subtly unreal, beauty edging into menace.

On release, The Madcap Laughs reached number 40 in the UK albums chart but went initially unreleased in the US, only appearing there in 1974 paired with the follow-up Barrett. Contemporary reviews were mixed but intrigued: Robert Christgau, for instance, described side one as “funny, charming, catchy - whimsy at its best,” even as other tracks seemed to him like documents of a “wimp-turned-acid-casualty.” Over time, critical consensus has shifted to see the album as a key document of the late-60s comedown, its mix of childlike melody, fractured structure and naked vulnerability embodying both Barrett’s personal unraveling and the end of the era’s utopian optimism. Remastered and reissued several times - notably in the 1993 Crazy Diamond box alongside Barrett and Opel, and again in 2010 - it continues to influence generations of songwriters drawn to its combination of intimate lo-fi immediacy and oblique, psychedelic lyricism. Heard today, The Madcap Laughs feels less like a polished debut than a diary salvaged from a collapsing house, pages shuffled but still humming with a strange, undimmed electricity.