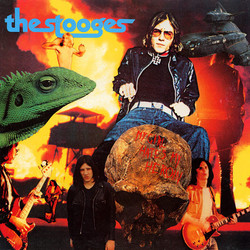

On release, Fun House baffled almost everyone. Sales were poor; one Melody Maker review called it “a muddy load of sluggish, unimaginative rubbish,” and even more sympathetic critics questioned whether music this extreme could function as “popular.” Over time, though, the record has been canonised as a stone classic: AllMusic hails it as the “ideal document” of the band, eMusic calls it “one of the most frontal, aggressive, and joyously manic records ever,” and Rolling Stone’s album guide has gone so far as to call it, hyperbole be damned, “one of the greatest rock & roll records of all time.” Its DNA runs through punk, post‑punk, noise rock and beyond: everyone from The Damned and The Birthday Party to generations of hardcore and garage bands has borrowed its riffs, its saxophone abuse, its principle that repetition plus volume plus unembarrassed abandon equals a new kind of freedom.

More than fifty years later, Fun House still doesn’t sound polite, dated, or fully assimilated. It remains, as one retrospective put it, “fatally out of synch” with the singer‑songwriter and blues‑rock decorum of 1970, which is exactly why it continues to feel like a live wire: an album that doesn’t just predict punk so much as make most later attempts at wildness sound slightly cautious by comparison.