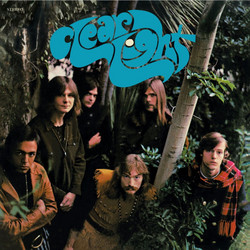

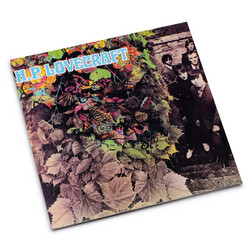

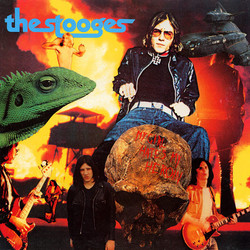

The record’s opening one‑two, “1969” and “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” still feels like a manifesto. “1969” starts with a wah‑wah feint, then snaps into a hypnotic, Bo‑Diddley‑by‑way‑of‑Ann‑Arbor groove, Iggy muttering about “another year for me and you” with a kind of slack despair that already sounds post‑everything. “I Wanna Be Your Dog” is even more drastic: three chords, a sleigh‑bell‑like shaker that refuses to stop, Cale’s single piano note hammered like a nail, Ron Asheton’s guitar scraping along the same riff until it becomes less accompaniment than blunt object. What contemporaries heard as crudity now registers as reduction: pop subject matter turned inside out into sadomasochistic mantra, harmonic language boiled down until nothing pretty is left.

Elsewhere, the album complicates its own legend. “We Will Fall,” a ten‑minute drone built on Cale’s viola and mock‑Gregorian chanting, drags the Velvet Underground’s dirge tendencies into a zone of ritual boredom that still splits listeners between awe and eye‑roll. “No Fun” and “Real Cool Time” show how far the band can stretch monotony into momentum - a handful of chords, a bass line that barely moves, and Asheton’s solos that sound like someone trying to stab their way out of the speaker cone, later adopted wholesale by the Sex Pistols. Even the much‑maligned “Ann,” a dirgey, almost Doors‑ish ballad, and the closer “Little Doll” contribute to the album’s through‑line of defiant slackness, everything recorded just murky enough to feel like you’re in the rehearsal room, not eavesdropping on an idealised version of it.