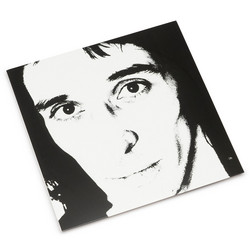

What makes Marquee Moon feel so singular is how much it relies on absence. The rhythm section plays with a light but unshakeable touch, Ficca’s drumming all feints and pivots, Smith’s bass driving without ever thickening the sound. Over that, Verlaine and Lloyd don’t stack power chords so much as braid barely overdriven lines, often in clean, chiming tones that leave enormous gaps in the spectrum. The opener “See No Evil” sets the template: a brisk groove, stabbing chords, a solo that climbs rather than shreds, lyrics about “I understand all destructive urges” delivered in a strangled, half‑yelp register. The band sounds exacting but never fussy, like a jazz unit that traded charts for streetlight and rehearsal rooms.

The title track remains the album’s vertiginous centre of gravity. Stretching past ten minutes, “Marquee Moon” uses repetition not as bludgeon but as hypnosis: a circular riff, simple changes, and then a long mid‑section where Verlaine’s guitar seems to detach from the song and orbit above it. That solo, recorded in one take and left essentially untouched, spirals through tension and release without ever tipping into excess, constantly referencing the rhythm while feeling like a separate narrative unfolding in real time. When the band finally snaps back into the song and Verlaine returns to the vocal, it feels less like a return to earth than like waking up in the same city with slightly altered eyes.

Around this centre, the record sketches a nocturnal map of New York. “Venus” wraps romantic calamity in chiming chords and one of Verlaine’s most effortless melodies; “Friction” curls its lip and lets the guitars gnash a little harder, nodding to Chuck Berry and early Stones while sounding unmistakably modern. The second side cools and deepens: “Elevation” lifts its chorus on the simplest of devices - a rising figure, a shouted title - while “Guiding Light” and “Prove It” tilt into more overtly lyrical, almost luminous territory, suggesting dawn creeping into a night‑long walk. Closer “Torn Curtain” drags itself across the floor, all slow chords and fogged emotion, underlining the album’s willingness to be impenetrable, even awkward, where another band might have aimed for a clear finale.

In the years since its release, Marquee Moon has been canonised almost to the point of cliché, yet the record continues to justify every list and poll slot it occupies. It regularly appears high on rankings of the greatest albums of the 1970s and of all time, and has been singled out as both a cornerstone of American punk and, more accurately, of the post‑punk and indie rock that followed. Guitar‑centric bands from Joy Division and R.E.M. onwards have cited it as a template for how two guitars can converse instead of merely doubling, while critics have described it as “the nearest rock record to a string quartet - everybody’s got a part, and it works brilliantly.” Heard today, Marquee Moon still sounds less like a period piece than a set of instructions that bands are somehow still trying to finish following: keep the sound lean, don’t fear sophistication, let the city bleed into the chords, and trust that if the song is strong enough, ten minutes is exactly as long as it needs to be.