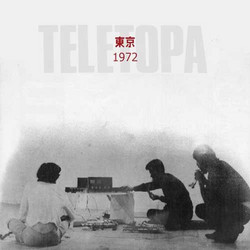

Teletopa

Tokyo 1972 (3LP)

Tip! *2022 stock* Some of the best recordings from Sydney's vibrant exploratory/spontaneous music scene ever released. Teletopa was “one of the earliest recorded examples of improvisation in Australia“. The trio was formed in Sidney in 1970 by Peter Evans, David Ahern and Roger Frampton, with various guests for each performance. Using conventional instruments like flute, saxophone, piano and percussion, Teletopa explored extended technique, unusual ways of playing, dissonances and silences, in a similar way as contemporary European groups Amm, Mev and Scratch Orchestra, of which David Ahern was a founding member during his stay in UK in 1969. This document is not just important for Australian music – it should establish them posthumously as one of the most interesting developments in experimental music anywhere in the world at this time.

Phillip L Ryan came up with the name ‘Teletopa’ for the group: ‘topa’, from the Greek tópos, meaning ‘the place of the origin of ideas’; ‘tele’, meaning ‘far, distant, an openness to any ideas whatsoever’. In this regard, Ryan contended that the activities of the group could (potentially) extend beyond music, while Ahern averred that the prefix ‘tele’ was indicative of the group’s willingness to use sound materials which may be found ‘in every corner of the globe.’ More recently, Ryan has recalled that, at the time he decided upon the name ‘Teletopa’, he was reading the work of the Japanese philosopher Kitaro Nishida and that the name of the group essentially means ‘distant field’, ‘field’ being apposite for the sound of Teletopa.

Ahern had been in London in 1969 where he attended Cornelius Cardew’s classes in ‘Experimental Music’ at Morley College and – in a mammoth seven-hour concert at the Roundhouse on 4 May – participated (with Cardew) in performances of La Monte Young’s String Trio and Terry Jennings’ String Quartet and also took part in the realisation of Paragraph 2 of Cardew’s The Great Learning which proved to be the catalyst for the formation of the Scratch Orchestra. During his stint in London, Ahern had the opportunity to hear the English group AMM (the membership of which then comprised Cardew, Lou Gare, Christopher Hobbs, Eddie Prévost and Keith Rowe). In comparison with other improvisation groups which were formed during the 1960s – in particular the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza and Musica Elettronica Viva (Rome) and the Taj Mahal Travellers (Tokyo) – AMM was the clear prototype for Teletopa, not only in regard to the type of improvisation Teletopa promulgated, but to the general ethos of the group as well. In fact, much of what has been said about AMM could apply equally to Teletopa. As Michael Nyman has pointed out, the membership of Mev, for instance, ‘frequently changed according to who happened to be around at any time; other musicians sat in and played with the hard-core members (Frederic Rzewski, Richard Teitelbaum, Alvin Curran, Allan Bryant) and were welcomed more openly than they were by AMM, extremely self-contained and private, basically hostile to “outsiders”.’

The membership of Teletopa was no less hostile to ‘outsiders’ than was that of AMM. In this way, the group was able to cultivate an identity which developed over time in which that of each of the individual players was subsumed. As a consequence, a viable, open form of music-making came about which hinged on a strong sense of communality and mutual aid within the group, what John Tilbury has referred to (in relation to AMM) as ‘a uniquely collectivist mode of playing.’

While Ahern, Evans and Frampton were the founder members, Linda Wilson also played with the group for the first three months, mostly on bowed cymbal. This culminated in a performance by Teletopa at the Sydney Town Hall on 16 February 1971, simultaneously with a realisation of Paragraph 2 of The Great Learning by an augmented AZ Music Ensemble, as part of that year’s Prom concert series. As local critic Frank Harris reported, the performance ‘was a disaster. Hundreds walked out in the first fifteen minutes and then the mob took over in a howling opposition which turned the concert into a near-riot.’ In an essay Ahern wrote prior to the formation of Teletopa, he insisted that ‘music is now able to be not so much “listened to” but “existed in”. One walks into a set of situations (art) just as one walks down the street (life).’ While this conviction had obvious implications for developments in the areas of sound environments and installations, it was also directly relevant to the type of improvisation Teletopa propagated: the group would invariably play for at least ninety minutes, often longer, at a fairly high level of amplification, with audience members free to come and go as they pleased.

It’s important to bear in mind that Teletopa utilised no electronic technology in performance other than contact microphones, which were used to amplify all sound sources. These sound sources ranged from conventional instruments such as violin (Ahern), saxophone (Frampton) and flute (Collins), to percussive devices such as cymbal (usually bowed or scraped), sheets of tin and masonite, plates of glass, various implements made of plastic, metal or wood and short-wave radio. On his way to Inhibodress, Frampton often collected objects he found lying in the street which he would then use in performance, necessitating the invention of playing methods for these objects. For a time during 1971, Frampton would attach an old alto saxophone to an Electrolux vacuum cleaner and allow the resulting sounds to issue forth unimpededly. In effect, this configuration of saxophone and vacuum cleaner was akin to the addition of another player. The sounds produced ‘were some of the loudest’ Frampton had ever heard. ‘They were completely unpredictable and totally fascinating.’ Teletopa’s quest for new or unknown sounds was often fraught with danger, yet such precariousness is an intrinsic part of the very fabric of free improvisation. In a review of Teletopa’s performance at Melba Hall, the Australian composer Ernie Gallagher was compelled to remark that ‘the importance of Teletopa sounds lie not so much with their life but with the nature of their death, their relevancy being moulded by the context in which they are created.

That is, for its purposes, the sound dies after its having been performed – otherwise it would no longer be Improvisation, no longer sound created “at the Instant of Now”.’ A little over a week after performing in the concert organised by Rands at the Cell Block Theatre, Teletopa embarked on a two-month overseas tour. The group had been invited by Stanley Lunetta and Arthur Woodbury, editors of the American new music journal SOURCE: music of the avant garde, to participate in ICES, the International Carnival of Experimental Sound, which was held in the UK from 13 to 27 August. However, the group first went to Manila, then to Rome, before linking up with Peter Evans in London, his duties in Calgary having concluded. Teletopa also had non-playing commitments in late August and early September in Munich, Cologne, Kassel, Hamburg and Amsterdam, interacting with composers such as Rzewski, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Mauricio Kagel during this time. The group returned to Sydney from Amsterdam via New York and Tokyo.

While in Manila, Teletopa functioned more as a contemporary ensemble than an improvisation group per se: in a concert at the CCP Little Theatre on 3 August, the group gave performances of Christian Wolff’s Duo for Pianists II and Steve Reich’s Piano Phase (Collins and Frampton, pianos), Ahern’s Stereo/Mono (Frampton, wind soloist), Frampton’s Things to do for Musicians and Stockhausen’s Set Sail for the Sun (from Aus den Sieben Tagen), in addition to an extended improvisation. In the UK, Teletopa performed at the Cambridge Union on 16 August and the Round- house on 23 August and also took part in events aboard the ‘Music Train’, an actual train which left King’s Cross Station on 21 August en route to Edinburgh with 600 musicians and artists on board. Regrettably, during the group’s time in England, marked tensions developed between Ahern and Frampton. According to Frampton, Ahern wanted to predetermine how the improvisations should flow, whereas he and Evans ‘felt obligated to improvise without regard to “standards”. We felt it was an inherent risk that improvisation would sometimes be more successful than at other times. David wanted to exercise more control, whereas Peter and I deliberately sabotaged David’s attempts to steer the music in a certain direction. Eventually these differences came to a head and Peter and I decided to leave the group on our return to Australia.’

Teletopa was in Tokyo from 14 to 26 September. Of major significance during the time spent there were the two studio improvisations featured on this double CD set, along with a performance by Collins and Frampton of Piano Phase, which were recorded by NHK Radio. Just prior to returning to Sydney, the group played in a ‘pub restaurant’, again in its guise as a contemporary ensemble, with realisations of Set Sail for the Sun, Cardew’s Treatise and How to Play the Piano (Frampton, piano solo) by the Australian composer Robert Irving. Sadly, these were the final performances ever given by Teletopa, with the group disbanding upon its return to Sydney.