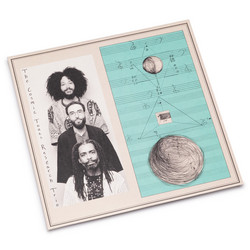

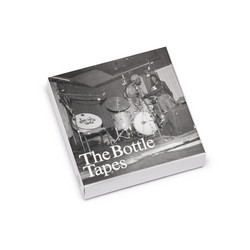

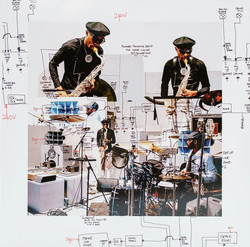

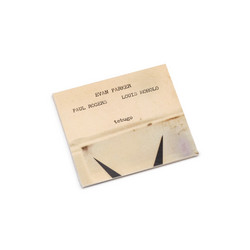

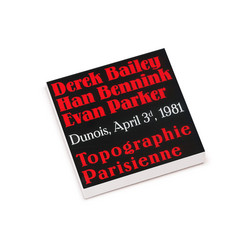

Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, George Lewis, Joelle Léandre

28 rue Dunois, juillet 1982

Awesome collective improvisation. "The fundamental tension between freely improvised music’s momentary existence in performance and the monumentalizing impact of media becomes more nuanced with each new delivery system. While MP3 files lack the totemic mass of box sets of discs, they nevertheless have a compensating spectral power. The rise of the archival recording compounds this tension, particularly when one is proffered to be the long-missing puzzle piece that completes the picture of how an artist or a movement evolved. Whether a newly discovered recording confirms the historical record, prompts revisions in dating and tracing musician networks, or upends academic tropes, the quality of its reception now is far from what it would have been at the time it was made. This will certainly be the case with Dunois ‘82, given the subsequent, entwined histories of Derek Bailey, Joëlle Léandre, George Lewis and Evan Parker, unless the music is heard in a contemporary context. Their respective activities during 1982 are representative of a year when the international improvised music network was rapidly expanding its circuits. Bailey spent the autumn and winter in New York, recording with Cyro Baptista, John Zorn and others, and convening the first Company outside of London. Parker toured Japan for the first time, which yielded his first solo tenor saxophone performance issued on disc. In June alone, Lewis recorded with Globe Unity Orchestra and participated in the London Company Week. Although Léandre still devoted considerable energies to the music of Cage, Scelsi and other composers, she was increasingly focused on improvisation when she met Lewis, Bailey and Parker in rapid succession; during her New York residency late in the year, she participated in Bailey’s Company.

Given the historical gravity these four improvisers now possess in the international improvised music community and its narratives, it is almost reflexive to listen to Dunois ’82 historically, to parse out what hundreds of subsequent recordings have confirmed to be signature methods and materials from what is more rare, even anomalous. In doing so, however, the music is stripped of what made it new: the energies of the times – well represented by the programming of Paris’ Théâtre Dunois, the site of Léandre’s renowned Carte Noire series a year later (which included both Bailey and Lewis) – and the palpable sense of an unconditioned chemistry between these musicians (to call them a quartet would be an inappropriate imposition of a group identity).

Some insist that freely improvised music has become a genre wrought with conventions; that its initial, fragmentary utterances, the coalescing banter that rises and falls (usually just once), and the often prolonged attempts to disengage, are as predictable as the development in a movement of a Beethoven piano sonata. Dunois ’82 refutes such assertions and the mode of listening that promotes them. More than 30 years later, this is still new music.