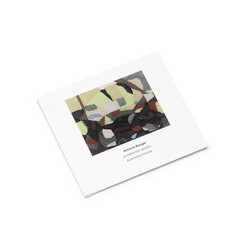

*Edition of 300* In recent years Swedish musician Linnéa Talp has grown interested in liminal spaces of sound, increasingly searching for her breath deep within passages of a song when instruments gently and patiently bridge the verses. In 2020 she released Cochlea, a brooding pop-rock record made under the name Deerest. “I’ve been trying to work with my body, my breath and my listening,” she says of her work since finishing that release. “I wanted to integrate a sense of slow and simple movement into the music—push/release, forward/backward, inhale/exhale—everything centered around being present, translated into sounding.” That transformation is evidenced on her remarkable new album Arch of Motion, a recording marked by exquisite patience and space.

While the recording explores similar terrain traversed by Stockholm composers like Ellen Arkbro and Kali Malone, Talp has carved out her own sonic space, masterfully blending unmediated experimentation with meticulously placed contributions by some of the country’s most accomplished improvisers, including singer Mariam Wallentin, trombonist Mats Äleklint, and reedists Martin Küchen and Christer Bothén.

This transformation was enabled in part by her first encounters with the Buchla synthesizer in a composition course she was taking several years ago. She approached the instrument with child-like openness, allowing herself to be surprised and proceeding without a plan. She trusted her instincts and let things happen, abandoning the desire to control the elements that went into her pop music. Talp then applied the same sense of wonder to the pipe organ.

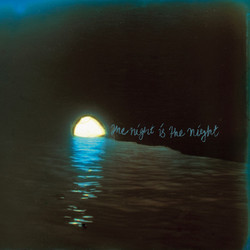

Further inspired by the ideas of John Cage and non-intention, she says, “When I started to work with my organ pieces, I tried to be open for whatever.” The organ parts on the album were recorded at several churches in the summer and fall of 2020, including Hörkens Kyrka, where the project started thanks to a compositional residency at Ställbergs gruva. “To be in a tone or a chord for a long time enables subtle details to appear and to expand, which is so fascinating,” she explains. “The organ is very suitable for this. There are so many possibilities—to work with vibrations, changes of timbre, microtonality, and to work with the sound of air, especially when slowly changing the registrations.”

The pieces on the album are concise, but very little editing was applied to those initial recordings. “My sense is that these pieces capture small amounts time, of me being present, sounding,” says Talp. Yet the relative brevity doesn’t hinder their revelatory power. After making these recordings she invited a handful of musicians to complement her solo excursions by adding complementary improvisations. “I wanted to add some color into the material, some additional movement, small changes in timbre and so on. The instructions that I gave the musicians was simply to do some quite free, but minimalistic improvisations. I told them to experiment with the timbre, with the octave, with small dissonances, with more or less air in the tone…things like that.” Working with producer Alex Zethson, she carefully selected passages from these improvisations, building out gorgeous harmonies and sympathetic shadings to enrich her playing without changing its essential nature.

These extra sounds are deployed with great subtlety, but careful listening reveals how these contributions add richness and almost inaudible counterpoint to the organ parts. On the short “To Whom” the wordless murmur of Wallentin vibrates alongside the pulse of the organ, with Küchen’s strident flute enhancing the upper register stop of the pipe organ, creating a single, extended gesture, while in “The Continuation” the organ sounds seem to blossom from the introductory bass clarinet long tones by Bothén, and the flute of Küchen later emerges like a rime upon Talp’s frosty chords. The title piece feels almost maximalist in context, with a cycling descending sequence out of which a low-end rumble, echoed in Äleklint’s almost imperceptible shadowing, and ethereal, fragmented tendrils of terse melody blossom.

On first glance these pieces suggest sonic inhalations and exhalations—it’s no surprise that Talp used words associated with breathing in the titles—but once the listener surrenders to these sounds, they notice that there’s much more happening. There is a simultaneous focus and release in Talp’s creative vision that can be deceptive in that way, but certain weightlessness of these pieces belies the rich detail and striations with each whoosh of sound. Talp demonstrates an acceptance and embrace in these small gestures as real building blocks of deep listening. They’re waiting for you to jump in.