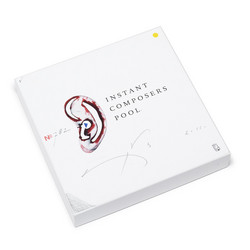

Instant Composers Pool, Nieuw Amsterdams Peil

De Hondemepper

"The road to this collaboration starts at the 1985 Holland Festival, when Hoketus—the flinty post-rock new-music ensemble founded by Louis Andriessen—premiered Rokus de Veldmuis (Rokus the Fieldmouse) by Misha Mengelberg (1935–2017). As Hoketus pianist Gerard Bouwhuis recalls, it generated some minor grumbling within the band; the chipper first movement appeared to mock Hoketus’s hard-edged seriousness. But the second half—“Een hutje van gras” (A Little Grass Hut)—was a wow: a hurtling triple canon including, Gerard notes approvingly, “this long middle section where ‘nothing’ happens, just a nice beat with irregular patterns: Misha goes Reich.”

That earworm stuck in his mind, for decades, ultimately leading to this pooling and piling on of ICP—the 10-piece orchestra Mengelberg founded, now with Guus Janssen on piano—and Nieuw Amsterdams Peil, flexible ensemble co-piloted by Bouwhuis and violinist Heleen Hulst. (This sextet version has Hoketus vet Patricio Wang on chromatic panflute and mandolin.)

Misha Mengelberg was good at thwarting expectations. Seven years before Rokus came the opulently melodic Dressoir, for another hammer-head ensemble Andriessen founded, Orkest de Volharding (who’d record it twice). This grabbag of short contrasting episodes—including a can-can, processional, sentimental plaint, dippy romp, and wake-the-sleepers closer—is superbly played here, a real charmer.

Mengelberg never fit comfortably into the worlds of post-bop jazz or modern composition; he was too gifted a diatonic melodist and too instinctive a saboteur of elegant or elaborate forms. But music so tuneful and subversive inspired acolytes drawn into ICP (tutored by the master to follow his thinking) and admirers without, such as Andriessen, Bouwhuis and Janssen. And then in the new century, Misha like other oblique geniuses put down for decades as a nutter, was belatedly lionized in time to savor it a little.

De Hondemepper spans Mengelberg works for various reading and improvising units: a Compleat Misha. The melded collective doesn’t feel like ICP with add-ons, or NAP augmented by ICP’s strings and reeds, but something new. The NAPsters dig into those finely wrought instrumental parts (Misha taught strict counterpoint at the conservatory after all). It was only prudent for them to consult ICP’s experts in Mengelbergian articulation, (self-) deprecatory gestures, and timing. With Han Bennink at the drums, tempos and time feel would be certified correct.

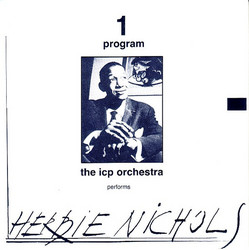

Four pieces honor Misha’s key influences, starting with his father. Karel Mengelberg composed his Trio in 1940—around when precocious Misha composed his first piece. (We hear the lento movement.) Thelonious Monk’s tone poem Reflections is heard in Michael Moore’s orchestration of Misha’s arrangement, with a panflute lead, and pocket jazz solos from bassist Ernst Glerum and tenor Tobias Delius. Guus Janssen’s chart for Herbie Nichols’ Cro-Magnon Nights, deploys triple clarinets, and forceful cro-mag horn howling, plus solos by Moore, Janssen and NAP’s bassoonist Dorian Cooke, who swings a bit herself. Ab Baars’ Pools and Pals, with its ICP-style swinging and open improvising and horn-section interventions, eventually tips its hat to Duke Ellington’s/Billy Strayhorn’s pirouette Depk.

Generations ago, when Dutch jazz and classical musicians began teaming up, they could drag each other down, reaching no consensus on phrasing or intonation. But Dutch ensembles (think Ebony Band) kept mixing jazz and classical repertoire and musicians, gradually raising everyone’s game. Dutch composers who smudged the jazz/classical line became common, and new compositional procedures/games infected their rowdy jazz-club bands, increasing improvisers’ resources. (Guus and Misha shared numerous musicians: Bennink, Moore, Glerum, Baars, Wolter Wierbos….) Working with a rigorous reading ensemble, ICP steps up: Moore’s clarinet covers the oboe part in Karel’s trio, the Wierbos/Thomas Heberer brass section is crisp on Dressoir’s fanfares, and the merged Pool/Peil strings tighten up—though saboteur Tristan Honsinger reserves the right to use his cello as disruptor gun, the way Misha used piano.

ICP, to be clear, is itself a mixed ensemble; violist Mary Oliver (like other ICPers) came from the realm of new composed music, and maintains a dual perspective. “Personally, this was a wonderful project for me,” she says. “I’ve played ‘A la Russe’ with Tristan and Michael, but playing it with NAP’s Dorian and Mick Stirling was a new lesson in interpreting its phrasing. The improvisations were a lot of fun: you could see on their faces how much they enjoyed getting out of their comfort zone and into our world. We all were invested in upholding Misha’s humor and power both.”

The proof is in the music. To hear De Hondemepper (Dog-Swatter: sexton tasked with shooing dogs from church) or ICP deep tracks from 1990 and 1986, Vieze en lekkere luchten and the Purple Sofa suite (à la Guus, exploiting percussionist Bart de Vrees’s bright colors and Bennink’s dark drive) is to confirm that Mengelberg’s serio-comic, natty-anarchic, ugly beautiful archaic modernist music remains elusive and beguiling as ever. Now that he’s gone, we are lucky there are folks who know how to play it right, and are ready to pass that knowledge on. The circle gets wider." – Kevin Whitehead / February 2020