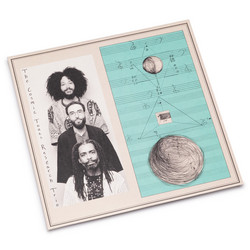

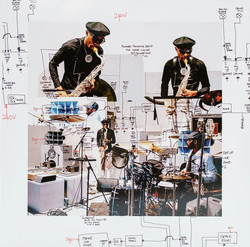

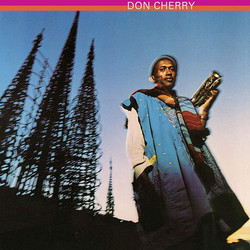

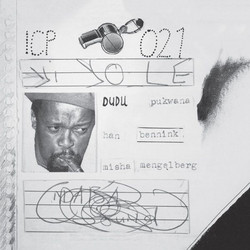

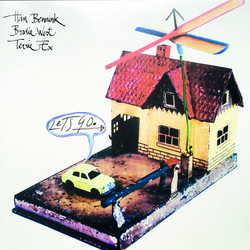

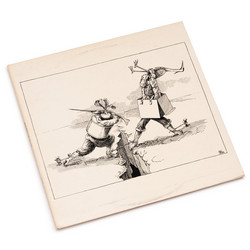

Fred Van Hove, Han Bennink, Albert Mangelsdorff

Elements, Couscouss de la Mauresque, The End (3 LP bundle)

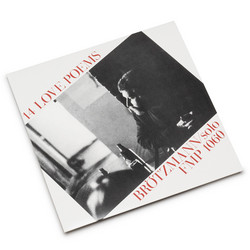

Since they first emerged on FMP in 1971, a series of recordings - often referred to as the Berlin Trilogy, have represented an axis point in the history of Jazz. Made earlier the same year by Peter Brötzmann, Fred Van Hove, Han Bennink, and Albert Mangelsdorff - Elements, Couscouss de la Mauresque, and The End quickly became legendary for their towering artistry and worth, but their larger contextual concern - with how they came to be, was an answer to a quite multilayered war being waged in the international musical avant-garde - one still unfolding in the history books today.

Between the mid 1960’s and the late 70’s, the iron grip of the Anglo European tradition was rattled free by a cluster of brilliant American improvisers. They were largely black and working class. Few had studied music formally - a slap in the face to almost every rational of the intellectual elite. These players - the bearers of what had been long understood to be a popular form, pulled the avant-garde from the hands of the Classical music world. Beginning with early slanderous remarks made by John Cage, a steady assault unfolded on this movement’s legitimacy and worth. Their gestures were unwelcome in the orthodox halls. To much surprise, through the cloud of cynical critique, it was in Europe that Free Jazz planted its most fruitful seed. Young members of a swelling countercultural recognized its power, found voice in its anger, cast division to the side, and waded in.

In hindsight, it’s easy to recognize countless distinct geographic traditions within the larger body of Free Jazz. It was, and remains, a global movement. Its two primary idioms - the American, and the European, are now offered near equal respect and distinction. Once hard fought questions of hierarchy and legitimacy have fallen away, but the balance was not easily gained. Though Europe was far more sympathetic and welcoming to Free Jazz than America ever was, it’s indigenous players were often in the wrong place at the wrong time - punks, out of step with the tide - caught in the cross hairs of cultural critique.

European Free Jazz has always been marginalized. It blossomed as the counterculture shifted toward psychedelia and Rock. Jazz fans, seeing this music as an American idiom, questioned authenticity - calling appropriation and pastiche. Even from within, it was a divided world. Some attempted to sculpt an autonomous European tradition - to shake it from American hands. Others sought collaboration with their international peers - to establish a new democratic international avant-garde form.

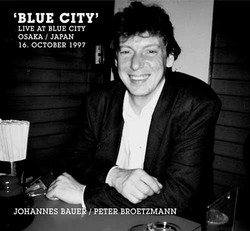

For many Peter Brötzmann is as good as it gets - the soaring patriarch of European Free Jazz - the emblem of its highest accomplishments and potential, but his context extends far beyond artistry and sound. He was among the first to balk divisionist thinking - seeking a network of players and collaborators which stretched across the globe. He was also among the earliest to challenge the idea of its being an exclusively American form - the very thing that brought the Berlin Trilogy to be.

Elements, Couscouss de la Mauresque, and The End were recorded over two nights - performances staged at the end of August of 1971, pointedly while Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, and a number of other American Jazz luminaries were in Berlin. As fans turned their heads, the gigs were an intervention - as much the raising of a middle finger, as the presentation of an alternate narrative and world view. European Free Jazz was stepping out on its own - as global and cross cultural as it was individual and distinct - a formidable competitor wading into the ring.

Fred Van Hove and Han Bennink formed the bedrock of Brötzmann’s endlessly elastic series of bands during this era - contributing a relentless steam of fierce recordings. By the early 70’s they had already created what many feel to be their seminal works - Nipples, Machine Gun and Balls - each growing from, and responding to, a context of deep social and political unrest - angry, storming works of energy and fire. The Berlin Trilogy finds them joined by the astounding but neglected trombonist Albert Mangelsdorff, and represents a changing of the tide - a shift toward a more thoughtful, subtle intricacy - a pluming of depths not found anywhere else - Free Jazz like it had never been. Autonomous, personal, and culturally specific, while equally in careful dialog with the whole.

Though often falling unjustly beneath the shadow of the Brotzmann band’s more well know works, Elements, Couscouss de la Mauresque, and The End represent a high-water mark in the history of European Jazz. Infused with the fire which made the group legendary, here their playing - infiltrated by Mangelsdorff, is sliced by stayed and retrained tempos, diverse textural passages and almost meditative response - sonorities winding themselves like an elastic band - stretched to breaking point and set free. This is four men listening - taking the intellectualism of sound to uncharted heights, passing beyond the realms of intuition and emotion - joining as one. Unquestionably among the most important recordings of 1970’s Jazz, their reemergence joins Cien Fuegos remarkable standing dedication to the history of European improvised music and the seminal output of FMP. Easily among the most important reissues that will emerge this year - not to be missed on any count.