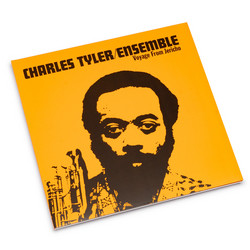

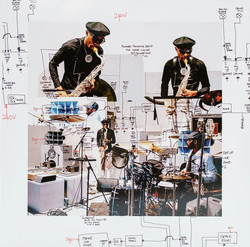

Charles Gayle, Szilárd Mezei Quartet (Bass)

Oils (CD)

In the second half of the eighties, I heard the duo of Charles Gayle and Peter Kowald at the Jazz Days in Novi Sad. A few years later, when Szilárd Mezei and I met, and played music together, I told him a lot about the experience that this concert had given me. I remember that the intensity, the density, the strikingly different quality of Gayle's music-making was beyond my comprehension, or even my measure.

And then the world changed, and what seemed unattainable at the time became reality. A joint concert could be created. This was, of course, due to the importance of Szilárd and his fellow musicians in improvisational music. He told me that during the negotiations, the only stipulation Gayle had was that he should receive a bottle of olive oil on arrival. This inspired Szilárd's title. The titles are playful variations on olive oil, like a children's story, a poetic miniature. Szilárd Mezei's scores are themselves works of art in their own right. That is how this recording came to be, as a beautiful, clear-cut score by Szilárd Mezei. Thinking of the work of Szilárd Mezei and Charles Gayle, I am reminded of Bresson's films, which are clean to the core. "There can be no relationship between an actor and a tree. They belong to two different universes. (The theatrical tree is only a simulation of the real tree)," he writes. This could be the difference between a musician and a Musician.

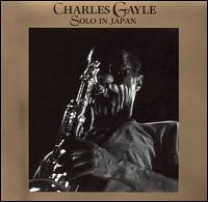

Elsewhere, Bresson writes of the human voice: "His voice draws before me his mouth, his eyes, his face, his complete external and internal portrait, more perfectly than if he were standing there before me. The most accurate means of cognition is mere hearing." Charles Gayle's music is of transcendent origin, it is soul music, an Artaudian rite of passage and a spiritual. His life's journey is not that of a conventional jazz musician, but rather a modern-day mystical quest, and it is perhaps by understanding this that his music can be interpreted (if music is to be interpreted at all). Gayle started as a professional musician. From 1970 to 1973, he was an adjunct professor of music at Buffalo State University, but grew tired of the responsibilities and left the university. He moved to New York to devote his life exclusively to music. He wanted to be independent of everything: music trends and living expenses. He gave it all up: he became homeless. Anyone moved by this romantic gesture should try spending three days on the street. Just as going out into the wilderness is not a romantic gesture, but a cruel and painful ordeal. Peter Kowald once heard Gayle playing in the streets, and it was thanks to him that he returned to the community and the stage after almost two decades.

Gayle's music has no frills. No outer space and astral flight, no Eastern transcendence. There are no exotic landscapes and moods. There is no mimicry of the external. There is no past, or future, only inward travel in a moment made infinite. There is no other type of journey but inward travel. The forms of the moment. The silence of dawn. The oily pulsation of the city at night. Rage. Sadness. Joy. At other times, he says that music teaches you duty, diligence, work, and integrity. To work hard to express yourself. That's pretty much it, he says. He also used to play a lot of music on Wall Street to earn a few dollars a day to survive, from young managers, bankers and stockbrokers who lived like emperors of life, earning thousands of dollars a day. Meanwhile, Gayle worked quietly alongside them. His music was a breath of fresh air. Diogenes of Apollonia said that the essence of the world is pneuma, air. In other words, air is also intelligence, smell (evoked by the air surrounding the brain), and sight (the pupil's contact with the inner air). Gayle is a witness. He is the witness to the destruction of a civilisation. What he sees is the all-consuming Fire.

For Szilárd Mezei and his fellow musicians, the freedom of the moment and the unity of pure forms and mathematical precision are important. This unity is only apparently paradoxical, because the moment of making music rises above everyday time and becomes a celebration. It all points to faith and the aspiration to live and work according to the law of a higher order. In this way, Mezei's work is also transcendent.

The meeting of two seemingly different worlds leads to tension, to an almost dramatic conflict. The meeting of two different worlds in the flesh. The stakes of this encounter are high, and you can feel the musicians are not playing a note inadvertently, the interplay of attention is condensed into a glowing magma. And on stage, Fire is born as a renewing, creative force. Chaos, out of which a face seems to emerge before it would explode. - Szabolcs Tolnai, film director