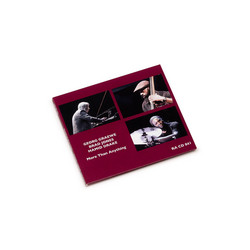

Charles Gayle, William Parker, Hamid Drake

Live At Jazzwerkstatt Peitz

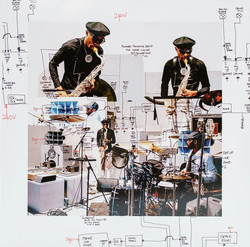

This performance from May 2014 was the opening concert at Jazzwerkstatt 51, given by Charles Gayle (tenor saxophone, piano), William Parker (double bass) and Hamid Drake (drums) in the Stüler Church, Peitz, Germany. The concert was dedicated “In Memoriam Peter Kowald”, the German bassist who died in 2002 and lived in New York for almost the last two decades of his life. Gayle and Parker were among his earliest musical associates in the city, as seen in the film Rising Tones Cross (full of now familiar faces, looking much younger). Gayle and Parker have been well documented together, but as far as I can tell this is the first commercial recording of them with Drake. The liner photo shows that Gayle played as “Streets the Clown” a funny nose and make-up he adopts from time to time as an onstage persona to create a distance from himself (when clowns cry, people take it seriously). For a number of years Gayle played alto saxophone, claiming that while homeless it was easier to put under his coat when sleeping, but the switch back to tenor now seems permanent. Gayle’s music – with its gospel-tinged, Ayleresque tunes – is rooted in a world in which the Church and music afforded some of the few redemptive moments in lives endured, combining deep sadness with the hope of salvation. Nowadays, his playing tends to be less fuelled by a relentless energy however, as if striving for a place where self is transformed through sound, feeling at times like a musical enactment of Jacob wrestling with the Angel. With the perspective of someone in their seventies – and the inevitable taking stock – Gayle’s playing has become sparser, with an economy of gesture typical of late work, but also no doubt due to the constraints imposed by age. His fiery spirit and sense of sanctity are still there, now more pensive than polemic. That isn’t always so – much depends on with whom he’s playing. 26.05.15 (Otoruko, 2016) is from London’s Cafe OTO (I was lucky enough to be there) with John Edwards on double bass and Roger Turner on drums, very much a return to the Gayle of earlier days: raucous and heroic in scale, spurred on by churning bass and drums. Shortly before, he’d played with Ksawery Wojcinski (double bass) and Klaus Kugel (drums) in Belgrade, a less turbulent pair and more meditative playing. This performance finds Gayle somewhere between the two. When they hit their stride, Parker and Drake are a rhythm section like no other, a supple unit made up from two different kinds of rhythmic motion, a weaving together of sometimes distinct pulses which complement and lock perfectly. There’s Drake’s intricate, floating polyrhythms and Parker’s lithe, throbbing bass line, incorporating phrasing and the repetition of notes typical of African string instruments. A perfect balance of lightness and weight, the fluid with metrical precision, and a propulsive power ranging from a swirling tornado down to a rippling stream. As with Gayle, there’s less of the former in this concert, possibly for the same reasons. Like Ayler, Gayle’s tunes are not only simple but wilfully simple: the ennoblement of the naive, and don’t undergo elaborate development. He uses them as inspirational verse, repeatedly interrogated, inducing a turmoil of exaltation and despair, often in contrasting registers, building into powerful crescendos which hang in suspense, frequently unresolved. On ‘Fearless’, when Gayle visits the tune for a second time with Parker on bowed bass, there’s a rising intensity as he’s compelled to move ever upwards, reaching the point where his saxophone squeals like a trumpet, only concluded by walking away while playing, fading and leaving the stage to Drake’s elegant solo. It is only the simple affirmation of the tune at the end of the piece which provides a release. Where possible, Gayle now divides his performances more or less evenly between tenor and piano, his first instrument. His pianism has been subject to the charge of too many notes, and sometimes tolerated as an eccentric excursion from his more serious work on saxophone. Gayle is committed however, and has released two albums of piano music: Jazz Solo Piano (Knitting Factory Records, 2001) – possibly a tribute to his days as a bar-room pianist – and Time Zones (Tompkins Square, 2006). He’s also taken further piano lessons. On saxophone, his musical and spiritual forbears are Coltrane and Ayler; as a pianist it’s Tatum and latterly, Monk, whose tunes he covers though snatches can appear elsewhere, as if stumbled on during his musings. Certainly, when Gayle switches to piano it’s a very different scenario and at first even Parker and Drake are thrown off-kilter, unsure of how to fit into this new space as Gayle carries on his own virtuosic disquisition on jazz piano, with frequent and abrupt changes in tempo and texture, rarely settled. Fascinating, but the kind of thing probably best played solo (Edwards and Turner accommodate this kind of nervous energy more easily). Here, the trio come together gradually however, as Gayle tempers his runs and becomes more focussed so that by ‘Angels’ they meld, finding a tone and pace that suits them all.

Gayle is back on tenor for the encore, celebratory rather than yearning, closing over Parker and Drake’s dancing groove.