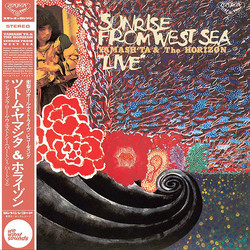

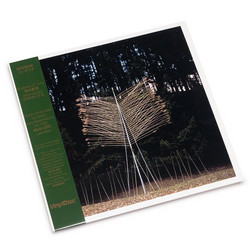

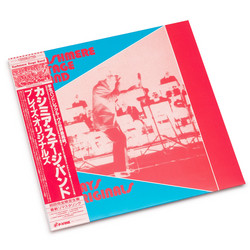

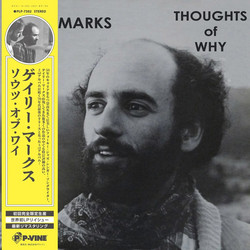

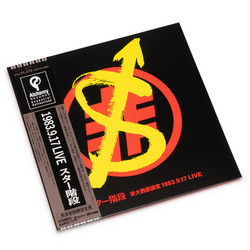

The 1980 album Friction (軋轢, literally “friction”) stands as the moment Friction stop being a rumour from the Tokyo underground and become a fully formed threat on record. It is their first LP and the only one to feature singer Masatoshi Tsunematsu as a full member, with production by none other than Ryuichi Sakamoto, who helps translate the band’s live volatility into a lean, sharply contoured studio language. Coming out of the Tokyo Rockers milieu and carrying memories of time Reck and Chico Hige spent in New York’s no‑wave circles (Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, James Chance & The Contortions), the group hit tape with an approach that treats punk not as three‑chord bash but as nervous, wired geometry: bass high in the mix, drums dry and anxious, guitar all slashes and scrape, vocals more barked commentary than sing‑along.

Across its ten cuts, the album feels like a catalogue of ways to weaponise repetition. Songs like “Crazy Dream” (often singled out as a standout) ride a handful of notes into something close to hypnosis, the band tightening and loosening around the central riff like a coiled spring. Elsewhere, tracks veer toward skeletal funk, with Reck’s bass carrying a thick, almost dub‑weight body while the guitar works in clipped, dissonant stabs that betray no‑wave ancestry more than straight UK punk worship. Tempos rarely explode into hardcore velocity; instead, tension comes from small drags and surges, from the way a hi‑hat pattern suddenly opens up or a vocal line snaps into a higher, more desperate register. Sakamoto’s production keeps everything close and unsweetened, foregrounding the band’s physicality and leaving in just enough room noise and grit to preserve the sense of a group playing on the edge of its own control.

Historically, Friction has come to be regarded as one of the foundational Japanese punk/alternative records, a release that “firmly established the punk and alternative rock scene within the Land of the Rising Sun,” as one retrospective put it. Its blend of avant‑garde roots, imported punk shock, and local sensibility set it apart from many Western contemporaries: where UK and US bands were already burning out on attitude and limited technique, Friction’s background in experimental music and New York’s underground meant their take on punk carried an extra degree of structural and textural curiosity. Over forty years on, reissues on labels like P‑Vine keep the album in circulation as a cult classic, and its buzzsaw tone and anxious groove can be heard echoing through later Japanese garage and noise‑leaning rock scenes. For listeners tracing the less Anglo‑centric histories of DIY music, Friction remains a crucial node: a record that shows how punk, once exported, could come back sharper, stranger, and more ruthlessly focused than before.