Delayed to June. After releasing the "minor epic" (the Wire) of Music for Church Cleaners a few years ago we're extremely extremely excited to be able to bring to you Áine O'Dwyer's new record 'Gallarais' on MIE Music. And thi sis

David Toop, on hearing Áine O’Dwyer’s Gallarais and the subsequent conversations between November 2016 and January 2017..."Twenty-six letters were sent, not far to travel, from Proust, hypersensitive writer to his upstairs neighbour, Marie Williams – ‘I was rather troubled by noise . . . I was trying to sleep off an attack. But at 8am the tapping on the parquet was so distinct that the Veronal didn’t work and I woke with the attack still raging.’ Marie Williams played harp, though it was not the harp that dragged Proust from the fumes of a bedroom armed against asthma attacks, cork-lined to smother noise. Hammerings disturbed him, the banging of carpet fitters, crates nailed shut. Similar disturbances creep into his books periodically: the ‘disagreeable’ noise of a newly installed heating boiler, ‘a sort of spasmodic hiccup’, which nonetheless served on every re-hearing to revive images of misty landscapes caught in his memory and ‘studied’ during the first morning the heater began its work. Proust spoke of an imperceptible breath, ‘like the wind breathing into the stem of a reed’, mingling with the subdued song of his dying grandmother’s breathing, ‘swift and light . . . gliding like a skater towards the delicious fluid’, the human sighs released at the approach of death, suggesting pain or pleasure ‘in those who can no longer feel’.

‘Who’s there?’ cries out the old man, stark terror pulled awake at the faintest of noises from pitch black vicinity of an unseen doorway. Harsh scrape, the tin fastening of a lantern, phantom heartbeat, subdued breath, asphyxiated breath.

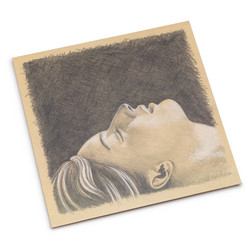

The interior is dimply lit, utterly dark even. There is one voice or two, whispers of shaping breath thrown into far obscure and occult recesses of the space as if spirits on the wing whose feathers shriek and keen. They are swans with near-human heads, carrying the lightness of souls, moving between dry land of the living, subterranean rivers of the dead. Sleep music they make, its murmurs written by the method of ‘passive writing’, a transcribing of tongues unknown to all but the most open of listeners. ‘To look at [animals] from an underworld perspective,’ writes James Hillman in The Dream and the Underworld, ‘means to regard them as carriers of souls . . . there to help us see in the dark. To find out who they are and what they are doing there in the dream, we must first of all watch the image and pay less attention to our own reactions to it.’

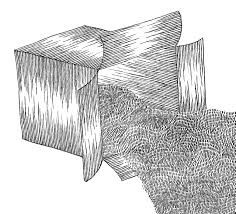

The space was a cave, a tunnel, a room without windows. A skull without eyes, ears, nostrils, mouth, though as Beckett had noticed, the soul turns in this cage as in a lantern, silence ‘beating against the walls and being beaten back by them’; the space was a chapel, upturned boat, perhaps the curragh that carried Maildun and his crew to the Isle of Weeping, the Isle of Speaking Birds, the Palace of Solitude.

‘Who is there? Is anybody there?’ A roaring encroaches on the silence and voices ascend out of water, wails of grief, in Dante’s world ‘no one there to make those sounds’. Voices flared in pitch black, spouting flame; buried in deep water, they rise up. Within a house described by Mary Butts, in Ashe of Rings, the bronze note of a clock rings, ‘like a body falling bound into deep water’. ‘Can you feel,’ says the guardian of rings to the woman, ‘now time is made of sound and we listen to it, and are outside it? Have you thought what it is to be outside time?’

The body descended into the tunnel, never to return as itself.