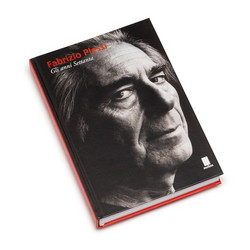

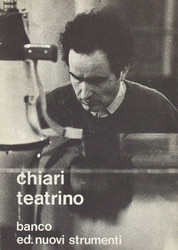

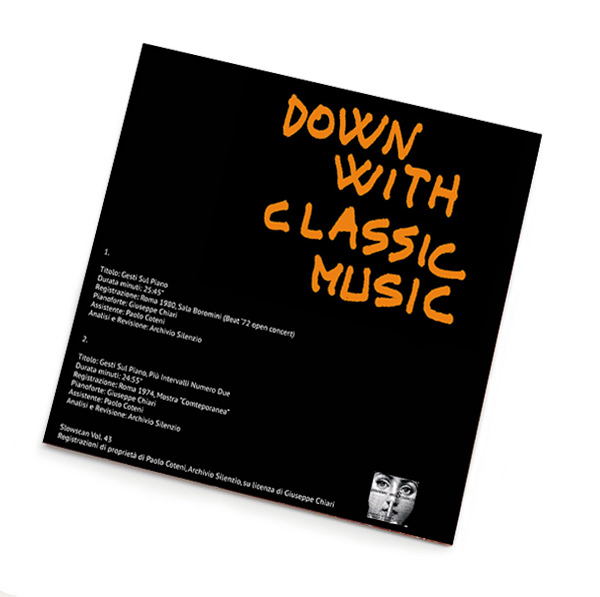

Edition of 250 copies, historical recordings from 1975 and 1980. Giuseppe Chiari was one of the leading names associated first with Fluxus (being the only Italian member of the interdisciplinary art group since 1962) and later with Conceptual and Performance Art as well as Sound art. Coming from a background of different disciplines, he established new theoretical and practical standpoints in relation to music and art: his approach was always irreverent, walking the tightrope between to do or not to do, to say or not to say, while continually challenging the limits of language.

Gestures on Piano is a center piece in his practice as artist and composer: in 1960 Chiari stopped composing music on the pentagram according to the tradition he had learned at school and took to the only music he could make, by acting in person wherever there was the possibility to play, playing with any instrument and in any place.

As did John Cage, who said that a composer is only someone who tells the others what to do, Chiari abandons the traditional statute of the composer to free himself (and free the others) from the alienation of the separate and hierarchic work which divides itself into composer/performer/ listener. The notion of totality is first of all an act of social revolt. Chiari accomplishes it by getting rid of another notion of which modern an is perhaps proudest, the notion of specificity of a language. Only now most people realize that to think in terms of specificity no longer allows to understand the complexity of the transformations of languages.

Thus, Chiari began publicly his new course with 'Gestures on the Piano' (in 1962), with actions 'Little Theater' ( New York , 1963). In the diagram of Expanded Arts drawn by Maciunas, the Italian musician who in Italy performs his own Fluxus concerts as well as other authors' Fluxus concerts, is placed in the 'Acoustic Theater' sector along with Cage, Riley, Tudor and La Monte Young. The Fluxus artist, as George Maciunas since 1962 has said, must teach thar all is art and that everyone can make it, because art must attend to insignificant things and must have no institutional value, must be amusing, must be illimitable in quantity and accessible to all. Chiari 's work adds to this pedagogic finality within recreation, turned toward the external universe of spectators, the awareness of being deeply engaged on the internal front of practice and theory; since one can teach norhing if one has not revolutionized his own discipline, his own science.