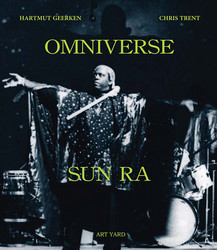

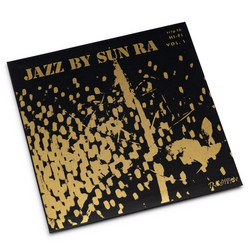

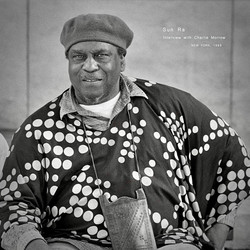

Temporary Super Offer! You know you're getting older — or just plain old — when you find yourself saying to younger people, "I'm hearing a lot about your rights, but what about your responsibilities?" or "Yes, freedom is a great thing, but what happened to discipline?" It's a valuable question, even if it takes grey hair to ask it. Freedom is one of the great fetishes of jazz, perhaps of modernism as a whole. A certain evolutionary model of the music has free jazz as a kind of logical destination, what happens when ad libbing is all there is left. But there are other models. We like to think of martinet bandleaders as a thing of the past: Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington in his proprietorial pomp, even James Brown, who'd fine musicians onstage for missing a beat. We're a little uncomfortable when biographers write about John Coltrane's fierce business brain or, coming straight to the music you are holding at the moment Sun Ra's turnkey discipline. The concept of the "Ra gaol", the toughest and most secure gaol there ever was, didn't come up in a critic's review; it was the boast of the man himself, the man born Herman Pool Blount in 1914 who renamed himself Le Sony'r Ra to espouse a new cosmic philosophy and radical revision of the swing and bop traditions.

I've heard Marshall Allen, present day keeper of the Sun Ra legacy, describe the leader's working method. It sounds demanding, and borderline capricious: arrangements changed at the shortest notice, parts reassigned to other instruments so that the whole complexion and direction of the music is changed, elements dropped without explanation. Hindsight often lends a warmer colouring to behaviour and personalities that were challenging-to-unpleasant at the time, but what is striking about the memories of the early Sun Ra Arkestra (and I managed to speak with the great John Gilmore about it all a few years before his death in 1995, as well as other Arkestra members) is how fondly and how seriously they committed to the disciplines of Sun Ra's music.

There are parallels — improbable though it might sound — between the Alabaman-Chicagoan and the French-Russian Nadia Boulanger, who, believing that she had no talent for composition herself, became one of the great music teachers of the 20th century. I thought of her quite spontaneously when listening again to the compositions on Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra. Volume 1 was the first Sun Ra record I ever owned and perhaps the first I ever heard. There is the same neoclassical simplicity and directness of line. The elaboration all comes from sound colour. There is the same resistance to volume as a dramatic device. Boulanger disliked fortissimo from an orchestra, in the same way that she didn't bellow at unworthy students; she simply told them they were no use and should give up. One of the things that strikes me about Sun Ra's discography, and since Heliocentric Worlds I have built up an obsessive's library of the stuff, is how very rarely, and always tellingly, he used sheer noise to make a dramatic point.

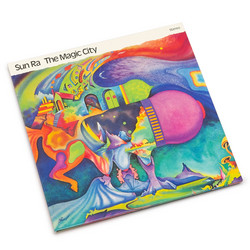

With Sun Ra, one always felt one had learned something; not the glib insights of a TED talk or the well-worn orthodoxy of the oldest professor in the department, but rather something that genuinely turned the head and reorganised thinking. I still get that from listening to Heliocentric Worlds ... No need of a lumpy distinction between "head" music and "heart" music. This is music that makes you think. It also conjures up a very specific time in American culture. The space race was heating up. Vietnam was heating up. The day Heliocentric Worlds, Volume 2 was recorded, a space craft was launched from earth that was to become the first to reach another planet (as opposed to moon or satellite). Unfortunately, perhaps, it was a Soviet rather than American craft, but it still meant that the solar system, which had gone through Ptolemaic, Copernican, Galilean and the modernist versions, was suddenly existential in a new way, part of the universe reachable by human means. In June, between the two Heliocentric Worlds sessions, an American man, Ed White, had exited Gemini 4 and actually walked in space, not in that nonsensical and unscientific vacuum we call "zero gravity", which is a classic misnomer, but freed from the bounds of earth for a moment and able to look down on our complex, beautiful little planet unhampered by wind or cold or bodily weight. NASA was always unimaginative in its choice of astronauts, picking the fit ones, good-looking ones and the ones least likely to cause embarrassment at a press conference. Imagine if they had sent Herman Sonny Blount up there, or back up there, as he might have insisted. What a different view of America and the world it dominated, he might have seen.

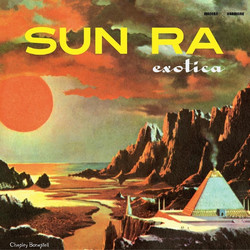

Of all the labels that have attached to his work over the years — Afrofuturism, experimental music, avant-garde, neo-swing — the one that makes most sense is "space music". It's also the one that most often misleads. It isn't all about flying saucers and alien civilisations, but it is about space, which is the dimension in which music functions. Has any composer/arranger ever used it more effectively? Listen again to Heliocentric Worlds ... but without dwelling on the scientistic or sci-fi title, and you'll hear — and see — what I mean ... - Brian Morton