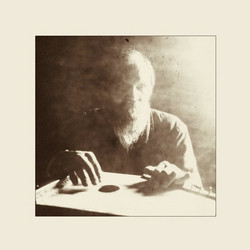

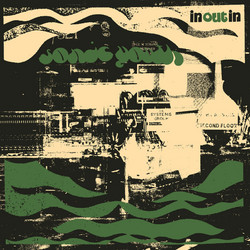

Jack Rose

Jack Rose (Lp)

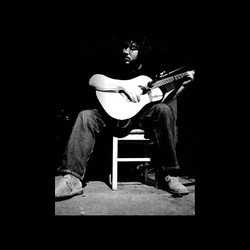

John Coltrane died at age 40, and in retrospect it seems as if the intensity of activity in his last years, the sheer torrent of notes, was an attempt at purging the music from his soul before it was too late. The guitarist Jack Rose died at 38, in 2009, and listening back to his catalog one has a similar notion. Like Coltrane, Jack Rose’s last years were marked by a shimmering intensity, an outpouring of his spirit, onto audiences and records.

I believe Jack Rose felt the duty of preservation but was by no means bound by it. With his virtuoso fingerstyle technique and restless guitar explorations--modal epics, bottleneck laments, uptempo rags--it’s easy to hear a connection to tradition and at the same time a pulsing modernism: “Ancient to the Future” in the words of Chicago’s Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. Ultimately, it’s no use attempting to explain the unexplainable (natural disasters, God, art, death). As the air gets heavy before a thunderstorm, Jack Rose’s vivid guitar picking awakes in us a peculiar awareness, something ancient and American. Jack Rose’s work exists along the established continuum of American vernacular music: gospel, early jazz, folk, country blues and up through the post-1960s “American primitive” family tree from John Fahey and Robbie Basho and outward to other idiosyncratic American musicians like Albert Ayler, the No-Neck Blues Band, Captain Beefheart and Cecil Taylor. His process can best be heard as an evolution; renditions of songs would transform over time, worked out live, with changes in duration, tempo or attack, in the search for a song’s essence.

The album known as “Self-Titled” was originally released in 2006 on the arCHIVE label, and later reissued as a CD two-fer with “Dr. Ragtime and His Pals.” It contains a combination of studio and live recordings. “Self-Titled” is marked by a sense of forward momentum, the result of several years of constant playing, with fresh versions of a number of previously attempted songs. Blind Willie Johnson’s spiritual “Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground” is manipulated into a wailing slide-guitar lament. “Levee” pops like a warning. “St. Louis Blues” (in this and its several other incarnations across his entire catalog) is a good example of Jack’s innate sense of swing, a crucial characteristic of his playing perhaps lost on some of his fingerpicking followers. The centerpiece of the album, however, is the nearly sidelong “Spirits in the House,” which begins with tentative weeping glissandos, and slowly reveals itself as a stately fingerpicked blues meditation.

Jack Rose was a larger than life man with a hearty spirit--a no-bullshit gentleman--and his death continues to reverberate among the community of musicians and music people he called friends. This spirit, as evidenced within his recorded output, has proven to be indomitable and continually vital.

8.3 Best New Reissue on Pitchfork. " 'Spirits in the House' is a composition that displays Rose’s obsessive tendencies; it is his single most gorgeous recording..."