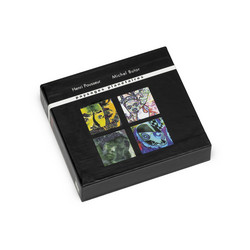

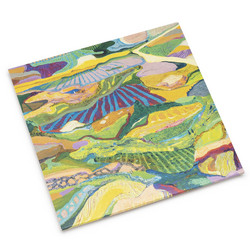

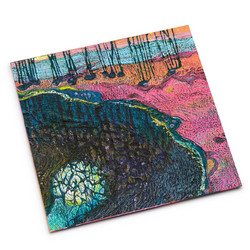

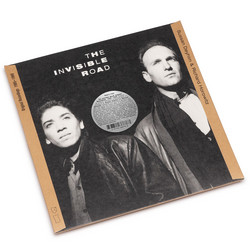

Todd Barton, Ursula K. Le Guin

Music and Poetry of the Kesh

CD edition. Buchla synth supremo Todd Barton’s hyperstitious soundtrack to Always Coming Home, an ‘80s American sci-fi novel by author Ursula K. Le Guin, is yet another ingenious recording dug out for reappraisal by Pete Swanson and Jed Middleman’s Freedom to Spend label - a division of RVNG Intl. Expect alien folk songs in made-up language, set to richly evocative backdrops of location recordings subtly gilded with self built instruments and synth contours. Properly immersive, otherworldly - think Breadwoman meets Lonnie Holley recording for Fonal.

“Music and Poetry of the Kesh is the documentation of an invented Pacific Coast peoples from a far distant time, and the soundtrack of famed science fiction author, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home. In the novel, the story of Stone Telling, a young woman of the Kesh, is woven within a larger anthropological folklore and fantasy.

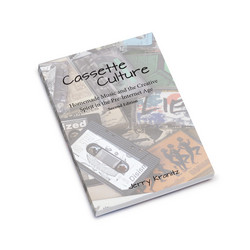

The ways of the Kesh were originally presented in 1985 as a five hundred plus page book accompanied with illustrations of instruments and tools, maps, a glossary of terms, recipes, poems, an alphabet (Le Guin’s conlang, so she could write non-English lyrics), and with early editions, a cassette of “field recordings” and indigenous song. Le Guin wanted to hear the people she’d imagined; she embarked on an elaborate process with her friend Todd Barton to invoke their spirit and tradition.

For Music and Poetry of the Kesh, the words and lyrics are attributed to Le Guin as composed by Barton, an Oregon-based musician, composer and Buchla synthesist (the two worked together previously on public radio projects). But the cassette notes credit the sounds and voices to the world of the Kesh, making origins ambiguous. For instance, “The River Song” description reads, “The prominent rhythm instrument is the doubure binga, a set of nine brass bowls struck with cloth-covered wooden mallets, here played by Ready.”

According to writer and long-time friend of LeGuin, Moe Bowstern (who pens the liners for the Freedom To Spend edition of Kesh), Barton built and then taught himself to play several instruments of Le Guin’s design, among them “the seven-foot horn known to the Kesh as the Houmbúta and the Wéosai Medoud Teyahi bone flute.” Barton’s crafting of original instruments lends an other-worldly texture to the recordings of the Kesh, not unlike fellow builders Bobby Brown and Lonnie Holley. Bowstern notes, “Other musician / makers have crafted their own Kesh instruments after encountering the earlier cassette recordings that accompanied some editions of the book.”

Both Barton and Le Guin are sensitive to the sovereignty of indigenous Californians and were careful not to trample the traditions of the Tolowa people who lived in the valley long before the Kesh. “You research deeply, and then you bring your own voice to the table,” said Barton. Within the Kesh culture, the numbers four and five shape the lives, society and rituals. Barton composed loosely around these numbers, patiently listening to the land of Napa Valley for signs and audio signals from the natural elements. Todd incorporated ambient sounds of the creek by Le Guin’s house and a campfire they built together.

The songs of Kesh are joyful, soothing and meditative, while the instrumental works drift far past the imaginary lands. “Heron Dance” is an uplifting first track, featuring a Wéosai Medoud Teyahi (made from a deer or lamb thigh bone with a cattail reed) and the great Houmbúta (used for theatre and ceremony). “A Music of the Eighth House” sends gossamer waves of the faintest sounds to “float on the wind.” Like the languages invented in the vocal work of Anna Homler, Meredith Monk, and Elizabeth Fraser, the Kesh songs and poems play with the shape of voice.”