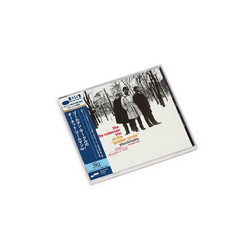

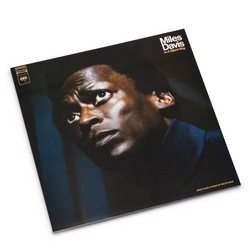

Miles Davis, John Coltrane

The Final Tour: Copenhagen, March 24, 1960 (LP)

Recorded at the Tivoli Konsertsal in Denmark in March 1960, The Final Tour: Copenhagen, March 24, 1960 captures Miles Davis and John Coltrane in the last, volatile phase of their partnership, just as Coltrane is about to break away and form his classic quartet. The band is the post‑Kind of Bluequintet: Davis on trumpet, Coltrane on tenor, Wynton Kelly at the piano, Paul Chambers on bass and Jimmy Cobb on drums, a rhythm team as unshakeable as it is combustible. The setlist is deceptively familiar - “So What,” “On Green Dolphin Street,” “All Blues,” and a closing “The Theme” - but the way the music is pushed, stretched and stressed makes this concert feel less like a victory lap and more like a pressure test of the very language they’d just codified in the studio.

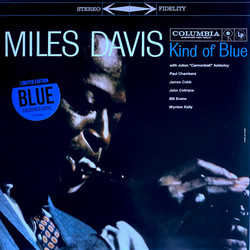

By early 1960, this group was already a legend in flux. Kind of Blue had been released the previous summer, but Bill Evans and Cannonball Adderley were gone, Evans replaced by the more hard‑swinging Kelly, while Coltrane was signing to Atlantic and recording Giant Steps and Coltrane Jazz. Davis, reluctant to lose another key voice, persuaded Coltrane to stay on for a final European tour, of which this Copenhagen concert is an early stop. The tension built into that arrangement is audible everywhere: the leader intent on maintaining form and atmosphere, the saxophonist clearly already pointed toward the next universe, and a rhythm section strong enough to hold both impulses at once.

“So What” opens the recording with Davis in commanding form, his sound burnished and centered, using space, inflection and sly motivic development to keep the modal frame alive rather than static. He leans on an extended turnaround device at the end of choruses, looping the harmonic tail while soloists keep playing, a device he would later refine into the “coded phrases” that stitched together his continuous sets in the late 1960s and 70s. Kelly, Chambers and Cobb respond with effortless propulsion: the piano lines are buoyant and blues‑touched, the bass deep and singing, the drums a mesh of ride‑cymbal glide and perfectly judged accents. When Coltrane enters, the temperature spikes: his lines pour out in long, dense ribbons, moving from the already fearsome “sheets of sound” into more extreme territory of multiphonics, overblowing and high‑register cries.

“On Green Dolphin Street” and “All Blues” show the same basic dynamic in different lights. On the standard, Davis plays with a kind of masked lyricism, floating over the changes while Kelly comping snaps the tune back into swinging relief. Coltrane’s solo, by contrast, sounds like an experiment conducted in public: repeated cells that mutate with each pass, phrases that deliberately lean against the changes, stacked harmonies that imply multiple chords at once. “All Blues” takes the modal waltz of the studio version and charges it with a rougher, more urgent energy, Cobb riding harder, Chambers walking with extra bite, Kelly spiking the texture with churchy stabs and hip voicings. Coltrane’s choruses here can feel almost overwhelming in their accumulation of tension - he famously told Davis “when I get going, I don’t know how to stop,” and the music bears that out.

What makes the Copenhagen document so gripping, though, is that it never collapses into pure conflict. Davis gives Coltrane the space to roam, perhaps sensing he was witnessing a necessary, if destabilising, evolution. The band, seasoned from years on the road, manages to frame even the most out‑leaning passages in clear, swinging time, which only heightens their impact. There are moments where Coltrane seems to be testing the physical limits of the tenor - altissimo screams, deliberately “wrong” notes, phrases that pile tension upon tension with no immediate release - and yet, when Davis re‑enters, the contrast reorients the ear, revealing just how elastic the forms have become.

As part of the Final Tour releases, this Copenhagen date has taken on the aura of a hinge point: the last extended document of Davis and Coltrane together before their paths diverged into the second great Miles quintet on one side and the spiritual fire of My Favorite Things and A Love Supreme on the other. The recording quality, sourced from a Danish radio broadcast, is clear enough to catch the bite of Davis’s Harmon mute, the grain of Coltrane’s overtones, and the conversational detail of the rhythm section, making it as much a study in small interactions as in grand gestures. For listeners, it offers both the pleasure of hearing canonical tunes re‑imagined at white heat and the thrill - sometimes uneasy, always compelling - of a band carrying within it the sound of its own imminent transformation.