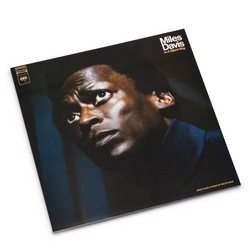

Sketches of Spain is where Miles Davis stops sounding like a jazz bandleader and starts to resemble a solitary voice moving through an enormous, reverberant landscape. Recorded between November 1959 and March 1960 at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio and released in July 1960, the album marks the third and most ambitious of Davis’s collaborations with arranger Gil Evans, following Miles Ahead and Porgy and Bess. What began as a plan to tackle just the adagio of Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez expanded into a full Iberian suite, drawing on Spanish classical repertoire, folk traditions and flamenco’s modal intensity to create something that sits at a strange angle to jazz, classical and so‑called “world music” alike.

The opening “Concierto de Aranjuez (Adagio)” occupies almost half the record and remains its gravitational centre. Evans, unable to obtain a full score, painstakingly transcribed Rodrigo’s guitar concerto from a recording, then re‑imagined the adagio for flugelhorn, trumpet and orchestra. Davis states the melody with an almost whispered authority, his flugelhorn tracing the line with such restraint that, as he later observed, “the softer you play it, the stronger it gets.” Around him, Evans opens the original into what his biographer called a “quasi‑symphonic, quasi‑jazz world of sound,” where woodwinds, brass and percussion swell and thin like weather fronts, threading hints of Arab and black African scales through Rodrigo’s harmonic frame. The piece is less a concerto in the classical sense than a slow ritual of emergence and withdrawal: Davis steps forward, comments, recedes, while the orchestra shifts from hushed gravitas to near‑catastrophic surges.

The rest of the album fans out from that cornerstone. “Will o’ the Wisp,” adapted from Manuel de Falla’s ballet El amor brujo, turns a brief, folkloric miniature into a delicately glowing vignette, Davis’s muted trumpet hovering over Evans’s translucent voicings. “Saeta,” drawn from an Andalusian cante hondo processional song documented in Alan Lomax’s Spanish Folk Music, places a stark, almost naked trumpet line against the funereal battery of drums and brass, evoking a Holy Week street ritual slowly transposed into orchestral language. “Solea,” inspired by a fundamental flamenco form that Miles linked directly to the feeling of the blues, closes the album as a kind of Iberian cousin to “Flamenco Sketches”: a slowly unfolding modal canvas where the orchestra moves in long, dark-red arcs beneath Davis’s aching lyricism.

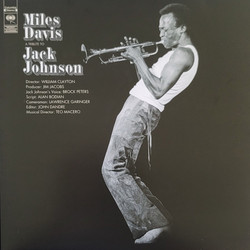

If Kind of Blue seemed to distil jazz down to a spontaneous, one‑take essence, Sketches of Spainwas its meticulous opposite. Sessions stretched over months, with Evans and producer Teo Macero demanding multiple rehearsals and retakes to refine balance, colour and phrasing; Nat Hentoff, observing a date, later described the process in Stereo Review as almost Herculean. The effort left Davis emotionally exhausted - “after we finished working on Sketches of Spain, I didn’t have nothing inside of me” - and he did not return to the studio for Columbia until 1961, turning instead to live recordings. Contemporary critics were divided, some questioning the lack of obvious swing or conventional jazz rhythm and even calling the Aranjuez arrangement a “curiosity and a failure” in comparison with classical guitar performances, while Rodrigo himself reportedly disliked the transformation despite the generous royalties it brought him.

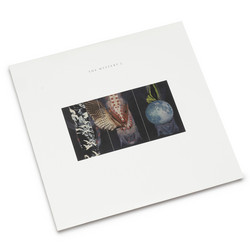

History has been kinder. Heard now, Sketches of Spain feels like a hinge work: the last of the great Evans collaborations, but also a stepping stone toward Davis’s later interest in long‑form mood, non‑American sources and expanded ensembles. Mobile Fidelity’s recent 65th‑anniversary edition, drawn from original tapes, underscores how carefully Evans’s orchestrations cradle Davis’s “pinched, lonely” trumpet tone, revealing new detail in woodwinds, French horns and percussion and softening the dryness some earlier pressings displayed. Above all, the album remains a study in how a single instrumental voice - often barely above a whisper - can hold its own against, and somehow humanise, a vast, meticulously constructed sound world, turning Spanish themes, flamenco inflections and orchestral colour into a single, slow‑turning tapestry of longing and restraint.