There were several ‘firsts’ involved in my initial encounter with Zygmunt Krauze’s music: my first visit to Poland (1970), my first ‘Warsaw Autumn’ festival and its first concert (19 September), and the Warsaw premiere of Krauze’s first Piece for Orchestra (1969). The memory has stayed with me ever since, not least because here was a work that was distinctly different from the other new Polish music that had so far filtered westwards. I was familiar with some Lutosławski, Penderecki and Górecki, but what struck me that evening was the restraint, delicacy and individuality of Krauze’s music. It stood out for being quiet, reflective and very beautiful.

I have long thought that Krauze has not always been given his due. He is, in fact, a great pioneer. His exploratory nature manifests itself in his abiding fascination with a certain inter-war painter, in improvisation, in new timbral combinations, at times incorporating folk or mechanical instruments, in spatial music and installations, and in being postmodern before the term had much musical currency.

His early absorption in the unistic creations of the artist Władysław Strzemiński – ‘compositions of minute, logically arranged parts emerging from the monochromatic surface of the canvas’, as Janusz Zagrodzki once put it – led to a piano work such as Five Unistic Pieces (1963) as well as to Piece for Orchestra no.1. Lest it be thought that Krauze’s music is always discreet and understated, in 1972 he paved the way for other Polish composers in using indigenous music as his material. Folk Music (1972) divides the orchestra into 21 motley ensembles playing a contrapuntal web of folk tunes, mainly from Eastern Europe, independently and mostly pianissimo possibile. The effect is veiled yet riotously colourful.

Part of Krauze’s genius comes from his experience as a pianist (he won the International Gaudeamus Competition for Performers of Contemporary Music in Utrecht in 1966) and as an improviser (he premiered Bogusław Schaeffer’s notorious graphic score, Nonstop). He uses imaginative extended techniques in his music for solo piano (Stone Music, 1972, Gloves Music, 1973). His ensemble Music Workshop (an idiosyncratic combination of clarinet, trombone, cello and piano) gave rise to innumerable works by Polish and foreign composers as well as some of his own most experimental pieces. Rustic instruments (hurdy-gurdies, bagpipes, folk fiddles, shepherds’ fifes, sheep bells) combine with improvisatory elements in Idyll (1974), while guitars, mandolins and music boxes feature in Automatophone of the same year.

Krauze began his ground-breaking exploration of installation art in the late 1960s, and in the original Fête galante et pastorale (1974) he combined six ensembles, including folk instruments, tape music and spatial aspects when it was premiered across 26 rooms at the Eggenburg Castle in Graz. In 1987, La rivière souterraine was performed at Metz in a specially constructed walk-through maze of seven ‘space cells’.

Perhaps most significantly, the ways in which different musical worlds rubbed shoulders with each other in Krauze’s music in the 1970s and beyond – while not abandoning the underlying unistic aesthetic – amounted to proto-postmodernism, way ahead of moves by other Polish composers and indeed many composers elsewhere. His large-scale piano solo The Last Recital (1974) is both serious and droll in its commentary on the relationship between new music and the past, and Krauze continues to be entranced by juxtapositions of genres and idioms. He composes with a unique subtlety and great inner strength, refracting his material through a semi-ironic, semi-abstract lens. There is no-one quite like him.

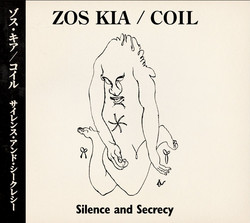

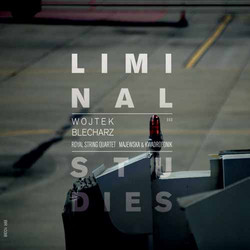

deluxe digipack + 10 page insert