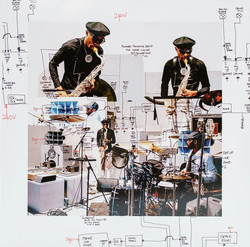

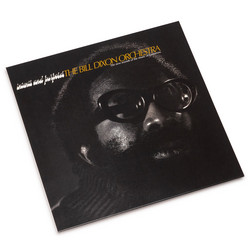

Bill Dixon

Live at Bennington College, 1969 (Lp)

**ltd/numbered 1/30, one-sided picture disk** extract ! historical doc/ensemble with Arthur Doyle at the fiercest !

.

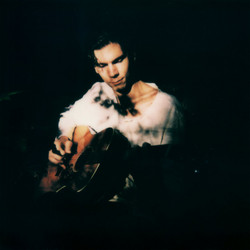

“Music to me [is] the universal language, the universal way of communicating.” For Arthur Doyle, saxophonist, flautist and vocalist, music was the life force, and Doyle’s dedication to the music had him playing fast and free jazz for most of his life. “That was my first love,” he once said to Patrick Marley, in an interview from Muckraker: “playing free and spontaneous.” Born on 26th June, 1944, Doyle grew up in Birmingham, Alabama with his parents and four siblings. He studied music education at Nashville’s Tennessee State University, and played in local R&B groups alongside local figures like Walter Miller (who was connected to the Sun Ra mothership), Louis Smith (who was playing with Horace Silver) and, perhaps most notably, backing the pre-Pips Gladys Knight.

Doyle’s first appearance on record was on Noah Howard’s The Black Ark, a legendary 1972 free jazz side that. Howard’s take on free jazz allowed space for Doyle to stretch his bell to its limits, but to get a true, unfettered sense of what he could offer group playing, Milford Graves’ 1976 album Bäbi sees Doyle blowing with the kind of unremitting fury that suggests that for some, the dream of the late ‘60s was still alive. In interviews Doyle repeatedly affirms how his music of this era was informed by the civil rights movement, by MLK, Malcolm X, the Black Panthers, the revolutionary fire of the time permanently imprinted on the brain, and in the very DNA of the music itself. This was also a very real presence in Doyle’s psychological life: after 1972, the pressure of the times led him to the first in a series of nervous breakdowns. In 1978, Doyle’s first album as leader, Alabama Feeling, was released on fellow musician Charles Tyler’s AK-BA label. It’s a particularly staggering set of fearless group improvisation, surprising for some of the instrumental approaches, particularly with the electric bass. While in a jazz context, this often screams “fusion,” Richard Williams’s grunting attack on the instrument is unhooked from formal constraints, playing with all the unchecked rawness and limber physicality of Doyle’s roaring, gutbucket sax, and the sea-sick whinnying of Charles Stephens’ trombone. The way Doyle and Stephens move from splayed torrents of rapid-fire notes to long, drawn-out, revenant moans, gasping for air while tones intermingle and cross-cut in the air, makes for some of the most thrilling free playing of its time.

The late ’70s and early ’80s saw Doyle shuttling between Paris and New York; in Paris, he sat in with Alan Silva’s Celestial Communication Orchestra, appearing on their Desert Mirage album, while in New York, Doyle had hooked up with No Wave man of mystery (and Ed Wood biographer) Rudolph Grey, who had first encountered Doyle on The Black Ark. Doyle’s velocity and extremity sat perfectly within Grey’s post-Red Transistor group, The Blue Humans, and the noxious clouds of noise and feedback strangled from Grey's guitar (the line-up was completed, at this stage, by Beaver Harris on drums). This trio would appear at the infamous 1982 Noise Fest, curated by Thurston Moore, though the only contemporaneous documentation of their music was “The Third Colour (Excerpt)”, from the Noise Fest cassette. But problems landed Doyle in jail across much of the ’80s; during his stint in prison, he would begin writing the several hundred songs that made up his personal “songbook.”