**In process of stocking** "We are creatures of habit and custom. Our minds like to run along familiartracks. A wise Russian folklorist tells us that there are really only five, oris it seven? basic stories and we learn to look for them. When we see a stringquartet come on stage, we think we know what we're going to hear, except thatdoesn't prepare us for one by Luigi Nono, which is mostly silence, or one by John Cage, where the players sit far apart and don't seem to communicate.Likewise, for a certain generation of jazz fans, a lineup consisting of trumpet,saxophone, bass and drums, with no obvious harmony instrument, invariablymakes us think about the great Don Cherry/Ornette Coleman quartets of the1950s.

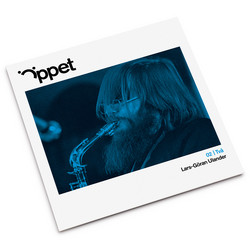

Marco von Orelli and Tommy Meier very quickly overturn that expectation. Ifwe have heard their work before, we will be prepared for something different,but it's a delightful surprise nonetheless. When the saxophone utters a bluesyphrase on "Five Dark Days" late on in the album, we might think that thelanguage is at last returning to some assumed norm, but for the most part thehorns are used as much texturally as they are for clear declamatory notes or forquick linear ideas. In the same way, even though we know that Coleman and Cherrywere largely constrained by the studio techniques and instrumental hierarchiesof their day, we recognise that even they would have wanted the bass and drumsmixed up higher and more prominently. In the group of von Orelli and Meierbassist Luca Sisera (who like all modern bassists owes a subtle debt to CharlieHaden) and drummer Sheldon Suter (who is the heir to a century of live researchinto the subdivisions of metre) are very much components of a collective, ratherthan supporting agents.

The music here is often darkly thoughtful, which is not to say that it isunexciting or "head" music rather than "heart" music. Anyone who hears vonOrelli's signature compositions, "Lotus", "Part of a Light", "Forbidden Fruits"(perhaps the most sensuous number) and "Triptychon" will come away smiling anduplifted. He knows and his colleagues know that jazz - if we're stillcomfortable with the term - is about joy and danger, grief and anger, that itconsists of serious consideration as well as spontaneous gesture. It is, inshort, a music that sets out from the beginning to confound rather than fulfilour expectations.

And yet, it has to rely on a language. Real aficionados always appreciateimaginative choices of repertoire and the presence here of lines by Americanmaster bassist Adam Lane and by the gifted Swiss saxophonist and composer CoStreiff is testimony to how thoroughly absorbed in new music this quartet is.And those same enthusiasts will perhaps look smilingly at the inclusion of atrack by Streiff's colleague and fellow-saxophonist Tommy Meier, a stillunderrated writer. It's called "Wittgenstein", a name and title that reminds usthat the limits of our language are the limits of our world, but also, as LudwigWittgenstein came to believe later in his life, that our language-world getsbigger and richer the more often we visit it and test its boundaries. Thatremains the abiding impression of this beautiful record. It matters very littlewhat preconceptions we bring to it. The music itself tells us where we aregoing. In tells us quietly but insistently, in breathy, almost toneless shapesfrom the trumpet, resonant frictions from the tenor saxophone and bass clarinet,low drones and rhythmic pulses from the contrabass, and a whole orchestra ofsounds - not just "time" - from the percussion. Lotus Crash is a marvellous newrecord from a new jazz imprint, which also has a great deal of history behindit, as well as a desire to move ever forward into the music's future."-BrianMorton