Best of 2025

1

2

3

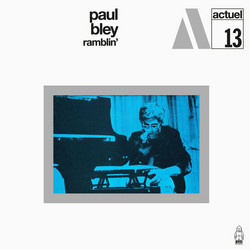

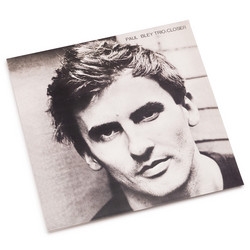

After Chick Corea’s Piano Improvisations, and Keith Jarrett’s Facing You, Paul Bley’s Open, To Love was the third fabulous chapter in ECM’s quietly revolutionary solo piano manifesto, whose impact endures and continues to influence improvisers today. In the liner notes to this Luminessence vinyl edition, Bley biographer Greg Buium writes, “After more than fifty years, Open, To Love remains an imperishable gem, lodged forever in the present tense, and among the great masterpieces in ECM’s vast catalogue.”

Produced by Manfred Eicher in Oslo in September 1972, the Canadian pianist’s album brilliantly integrates three strands of material into a sweeping and emotionally powerful narrative arc. Repertoire is comprised of songs by Carla Bley and Annette Peacock (Carla’s “Closer”, “Ida Lupino” and “Seven”, and Annette’s “Open To Love” and “Nothing Ever Was, Anyway”), plus two pieces by Paul which unspool and reconfigure jazz standards. In “Harlem” and “Started”, Bley fragments motivic material from “I Remember Harlem” and “I Can’t Get Started”, pieces he had played through the bebop years, until the music acquires a surrealistic dreamlike character, meshing perfectly with new visions of free balladry.

Details

Cat. number: ECM 1023

Year: 2025

Notes:

Recorded September 11, 1972 at Arne Bendiksen Studio, Oslo.

An ECM Production

℗ 1973 ECM Records GmbH

CD is manufactured by PolyGram in Hannover, West Germany

Printed in W. Germany