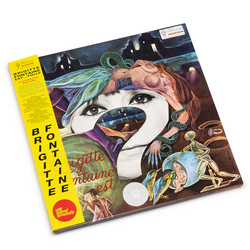

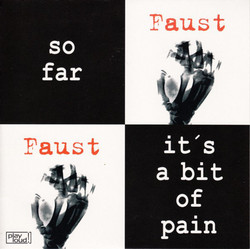

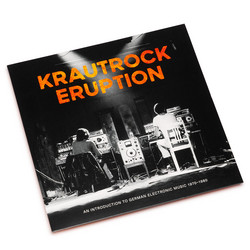

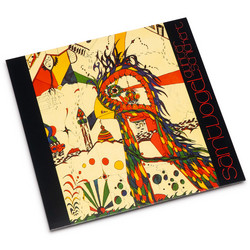

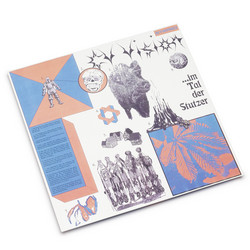

Wümme, Lower Saxony. 1972. A converted schoolhouse. Inside: a tangle of cables, reel-to-reel machines, custom electronics soldered together by hands that refused manuals. This was not a professional recording studio. This was Faust's laboratory—and So Far was the experiment that proved you could rewire rock music's circuitry without killing the patient. Six months earlier, Faust had released their self-titled debut—a savage dismantling of what a rock album could be. Tape edits sliced through songs like scalpels. Abstract structures replaced verse-chorus-verse. Cultural detritus—found sounds, radio interference, screaming electronics—collaged into something that felt less like music and more like controlled demolition. The album didn't ask permission. It kicked the door down.

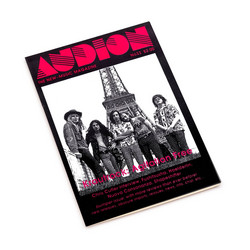

So Far is what happened next. Not a retreat from radicalism, but its evolution. Where the debut exploded rock from the inside out, So Far rearranges the wreckage into strange new shapes. The fragments almost, almost, resemble songs. There are rhythms you can follow. Melodies you can hum—for a few bars, before they dissolve into tape manipulation or collapse under their own weight. But don't be fooled. This is still Faust: unpredictable, subversive, unbound by convention. By 1972, the band had grown more cohesive as a unit. Jean-Hervé Péron, Werner "Zappi" Diermaier, Hans Joachim Irmler, Rudolf Sosna, and Gunther Wüsthoff weren't just musicians—they were sonic architects, building structures that shouldn't stand but somehow do. The Wümme schoolhouse gave them space to think sideways, to follow impulses that would have been edited out of any conventional studio session. Their label, Polydor, was getting nervous. Where was the hit single? Where was something—anything—they could market to radio? Faust responded by going deeper into the maze.

There's a sly humor buried under the fuzz and tape edits, a knowing wink that these sonic detours aren't acts of nihilism but of creation. Faust were building something. What, exactly, remains elusive—and that's precisely the point. So Far doesn't answer questions. It opens doors you didn't know were there, then walks through them without looking back. This is krautrock at its most playful and its most dangerous. Where Can locked into groove and Neu! hypnotized through repetition, Faust preferred chaos theory—patterns that emerge, then scatter, then coalesce again in unexpected configurations. Listen to how a simple guitar line twists into something unrecognizable. How drums lock in, then deliberately fall apart. How voices surface from the mix like ghosts in the machine, singing melodies that feel familiar until you realize you've never heard them before.

Taken as a whole, So Far is less a linear progression from Faust's debut than a sideways leap into a parallel sonic dimension. It's the sound of a band refusing to repeat themselves, even when repetition would have been easier, more commercial, more logical. Faust weren't interested in logic. They were interested in possibility—in what happens when you treat rock music not as a fixed form but as raw material, infinitely malleable, waiting to be shaped by hands willing to take risks.

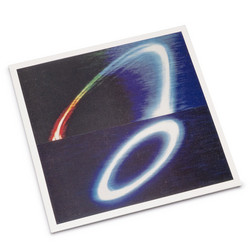

Bureau B now presents So Far on blue vinyl—a physical object as strange and beautiful as the music it contains. For anyone attempting to understand how rock music came apart in the early 1970s, how it fragmented into a thousand experimental directions, this album is essential evidence. The schoolhouse in Wümme is long gone. But the music created there—utterly intoxicating, still untamed—endures.